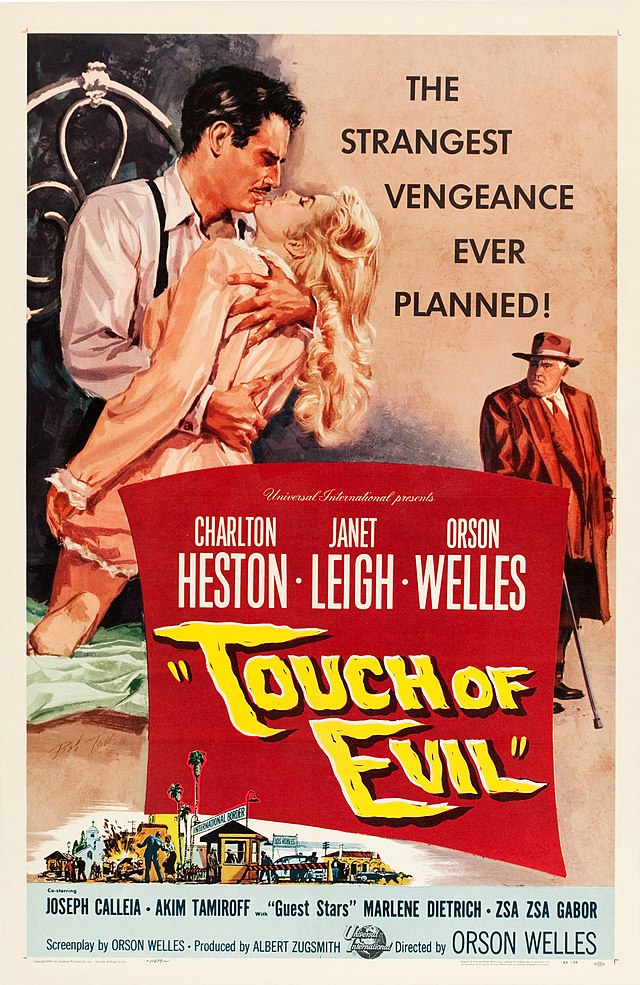

Touch of Evil - 1958

back| Released by | Universal International |

| Director | Orson Welles |

| Producer | Albert Zugsmith |

| Script | Orson Welles (screenplay); based on the novel Badge of Evil by Whit Masterson |

| Cinematography | Russell Metty |

| Music by | Henry Mancini |

| Running time | 95 minutes |

| Film budget | $900,000 |

| Box office sales | $2.25 million |

| Main cast | Charlton Heston - Orson Welles - Janet Leigh - Joseph Calleia - Marlene Dietrich - Zsa Zsa Gabor - Ray Collins - Akim Tamiroff |

Touch of Evil

A Masterful Film Noir

Touch of Evil (1958), directed by Orson Welles, is a film noir masterpiece set in a corrupt, decaying border town between the U.S. and Mexico. The story follows Mexican narcotics officer Vargas (Charlton Heston) as he clashes with the corrupt American police captain Hank Quinlan (Welles) after a car bombing.

As Vargas investigates Quinlan's unethical methods, including planting evidence, his wife becomes endangered by local criminals. The film explores themes of corruption, morality, and justice, with Quinlan's downfall serving as a tragic portrayal of moral decay.

Despite being initially mishandled by the studio, Touch of Evil has since become one of the most critically acclaimed noir films, praised for its innovative direction, iconic long tracking shots, and complex characters. Its influence on visual storytelling and its exploration of ethical ambiguity have cemented its place in film history.

Related

Touch of Evil – 1958

Summary of Touch of Evil (1958):

Touch of Evil opens with one of the most famous long takes in cinema history: a tracking shot that follows a car as it travels through a seedy Mexican border town, ultimately exploding just as it crosses into the United States. This event sets the plot in motion, as Ramon Miguel "Mike" Vargas (Charlton Heston), a Mexican narcotics officer on his honeymoon, becomes involved in the investigation of the bombing.

The car’s occupants—a wealthy American businessman and his young mistress—are killed in the explosion, and the case is assigned to Captain Hank Quinlan (Orson Welles), a corrupt and obese local police officer with a reputation for always solving his cases. Quinlan quickly fingers a young Mexican man, Sanchez, as the culprit. However, Vargas begins to suspect foul play when Quinlan "finds" incriminating evidence in Sanchez's apartment—a practice that Vargas believes Quinlan has used before to secure convictions.

As Vargas begins his investigation into Quinlan's past, his new wife, Susan (Janet Leigh), becomes a target of local criminals. Quinlan, threatened by Vargas’s scrutiny, teams up with “Uncle” Joe Grandi (Akim Tamiroff), a crime lord who holds a grudge against Vargas, to discredit him and intimidate Susan. Grandi orchestrates a plot to frame Susan for drug use and disgrace her.

Vargas’s investigation intensifies as Quinlan's questionable methods come to light, revealing the extent of his corruption. Quinlan, once a celebrated detective, has been planting evidence for years, often justified by his own sense of moral superiority. His partner, Pete Menzies (Joseph Calleia), who has always admired Quinlan, starts to have doubts when Vargas presents evidence of Quinlan's wrongdoing.

The tension escalates when Quinlan kills Grandi in a fit of rage after the gangster begins to blackmail him, leaving Susan in a vulnerable position. Vargas, desperate to clear his wife’s name and bring Quinlan to justice, manages to convince Menzies to help him trap Quinlan. They secretly record Quinlan confessing to his crimes. In the final confrontation, Quinlan, wounded and betrayed by Menzies, dies in a canal—an end befitting his tragic fall from grace.

The film closes with a melancholic tone, as Tanya (Marlene Dietrich), Quinlan's old acquaintance, delivers a chilling, fatalistic line about Quinlan's demise: “He was some kind of a man. What does it matter what you say about people?” This epitaph serves as a poignant commentary on the morally ambiguous world of the film.

Analysis of Touch of Evil:

Themes of Corruption and Morality: At its heart, Touch of Evil is a film about corruption—both personal and institutional. Captain Hank Quinlan represents the rot at the core of the American legal system, a figure who believes the ends justify the means, even if it requires breaking the law. His willingness to plant evidence, manipulate investigations, and frame suspects stems from his belief that he knows what’s best, and that his “justice” supersedes legal ethics.

Vargas, in contrast, is an idealistic Mexican officer who represents the moral center of the film. His dedication to uncovering the truth sets him apart from Quinlan, though his moral righteousness puts his own life and his wife’s safety at risk. The film plays with this dichotomy, exploring the tension between law, justice, and corruption, as well as the dangers of self-righteousness.

Character Study: The film’s central conflict between Vargas and Quinlan is a study in contrasting personalities. Vargas is honorable, driven, and unyielding in his pursuit of justice, but his dedication blinds him to the danger he is putting Susan in. Meanwhile, Quinlan is a tragic figure—brilliant yet corrupt, physically decaying as his morality withers. Welles’s portrayal of Quinlan adds a layer of sympathy to a character who might otherwise be a straightforward villain. Quinlan’s alcoholism and bitterness suggest a man who was once good but has succumbed to his worst instincts over time.

Susan’s character, while often criticized for being underdeveloped, serves as a symbol of vulnerability in the face of corruption. She is used as a pawn by both Quinlan and Grandi, and her peril underscores the personal costs of Vargas's crusade.

Cinematography and Style: Orson Welles’s direction is perhaps the most celebrated aspect of Touch of Evil. The opening tracking shot is a technical marvel, drawing the viewer immediately into the chaotic world of the border town. Throughout the film, Welles uses low angles, deep shadows, and claustrophobic framing to create a sense of unease, fully embracing the aesthetics of film noir. The film’s visual style reflects the moral ambiguity of its world, with characters often emerging from or disappearing into darkness.

The cinematography by Russell Metty is key to this atmosphere, making full use of the interplay between light and shadow. The noir elements are pronounced, from the smoky interiors to the nighttime settings that amplify the tension. Welles also makes great use of close-ups, emphasizing Quinlan’s grotesque physicality and Vargas’s intensity, driving home the personal stakes of the conflict.

Music and Atmosphere: Henry Mancini’s score is another standout feature, blending jazz and Latin-inspired rhythms to reflect the border town’s cultural clash. The music adds an air of danger and unpredictability to the film, underlining the tension between the characters and the murky moral landscape they inhabit. Mancini’s score is as much a part of the atmosphere as the cinematography, contributing to the uneasy, almost dreamlike quality of the narrative.

Social Commentary: While Touch of Evil is ostensibly a crime thriller, it also touches on issues of race and power. Vargas, as a Mexican official, is constantly viewed with suspicion by the American authorities. His authority is undermined throughout the film, and the tension between the Mexican and American characters reflects the broader anxieties about immigration, national borders, and cultural identity. In this sense, the border town setting is not just a physical space but a metaphor for the crossing of moral and ethical boundaries.

Legacy: Although Touch of Evil was not a commercial success upon its release, it has since been recognized as one of the greatest achievements in cinema history. The film’s complex characters, morally ambiguous plot, and innovative visual style have influenced countless filmmakers. Its critique of the corrupting nature of power remains relevant today, and Welles’s performance as Quinlan stands as one of the most memorable in film noir history.

In sum, Touch of Evil is a masterclass in suspense, atmosphere, and character study. It explores the dark side of human nature and the corrupting influence of power, all while delivering a tightly wound narrative that keeps the viewer on edge.

Classic Trailer Touch of Evil

Full Cast

- Charlton Heston as Ramon Miguel "Mike" Vargas

- Orson Welles as Police Captain Hank Quinlan

- Janet Leigh as Susan Vargas

- Joseph Calleia as Pete Menzies

- Akim Tamiroff as "Uncle" Joe Grandi

- Marlene Dietrich as Tanya

- Joanna Moore as Marcia Linnekar

- Ray Collins as District Attorney Adair

- Dennis Weaver as The Night Manager

- Val de Vargas as Pancho

- Mort Mills as Al Schwartz

- Victor Millan as Manolo Sanchez

- Lalo Ríos as Risto

- Michael Sargent as Blaine

- Keenan Wynn as Police Captain Gould

- Wayne Taylor as Casey

- Gus Schilling as Bartender

- Harry Shannon as Chief of Police Gould

There are also a number of uncredited performances, including:

- Zsa Zsa Gabor as Strip-club owner

- Mercedes McCambridge as Gang leader

Orson Welles’ Masterful Direction

Orson Welles’ direction of Touch of Evil is widely regarded as a masterclass in cinematic technique, blending innovation with a deep understanding of film language. His direction elevates the film beyond a conventional noir thriller into a complex exploration of moral decay, identity, and corruption, all while using a striking visual and aural style.

Visual Style and Cinematography

One of the defining characteristics of Welles' direction in Touch of Evil is his exceptional use of the camera. His approach to cinematography, with the help of his trusted cinematographer Russell Metty, is daring and highly stylized. Welles embraces the aesthetics of film noir—deep shadows, low angles, and high-contrast lighting—but adds his own innovative touch.

- Opening Scene: The film’s iconic opening scene, a three-minute-long tracking shot, is a prime example of Welles’ ambition and technical skill. The shot follows a car rigged with a bomb through a crowded Mexican border town, establishing both tension and the geography of the setting. Welles uses this sequence to draw viewers into the world of the film before any dialogue is spoken. The single-take tracking shot was revolutionary at the time, and it showcases Welles' belief in immersive, uninterrupted storytelling.

- Deep Focus: Welles, who famously used deep focus in Citizen Kane (1941), continues to experiment with it in Touch of Evil. He frequently stages scenes with significant depth, where objects and characters in both the foreground and background remain in sharp focus. This technique allows him to create layered, multidimensional images that reflect the complexity of the characters and the narrative. It also adds tension, as audiences can see events unfolding in the background, contributing to the suspense.

- Low Angles and Composition: Welles uses low-angle shots to exaggerate the imposing physicality and moral decay of Captain Hank Quinlan, played by Welles himself. These low angles make Quinlan appear larger and more grotesque, visually representing his overwhelming presence in the story and his dominance over the other characters. Welles often fills the frame with tilted, off-center compositions, reflecting the moral imbalance in the world of the film.

Atmosphere and Setting

Welles creates a world that feels claustrophobic, corrupt, and morally ambiguous. The town where the film takes place is portrayed as a decaying, dirty border town—a place where law and order barely exist, and boundaries, both literal and metaphorical, are blurred. Welles uses sets and locations to build a sense of decay, from the dingy motel where Susan is terrorized to the dimly lit, seedy streets filled with shadows.

The border town setting is crucial to the film’s theme of crossing boundaries—between law and criminality, between good and evil. Welles’ direction of the environment is so detailed that the setting becomes a character in itself, amplifying the atmosphere of distrust and corruption.

Pacing and Narrative Structure

Welles structures the film in a non-traditional way, blending elements of suspense and mystery with moments of character study and psychological tension. The pacing is tight, especially in scenes involving the investigation or confrontation between Vargas and Quinlan, but Welles allows moments of stillness where characters can reveal themselves through subtle interactions or monologues.

- Psychological Depth: Welles places great emphasis on character development, especially with Quinlan. Through Welles' direction, Quinlan’s moral descent is presented not just as a plot point, but as a psychological unraveling. The audience sees Quinlan not just as a villain but as a tragic figure, a man who has fallen so far into corruption that he justifies his criminal actions as necessary for justice. Welles' portrayal of Quinlan is both monstrous and sympathetic, which adds to the film’s complexity.

- Disorientation and Suspense: Welles uses disorienting camera angles, sudden cuts, and distorted sound to create a constant sense of unease. This disorientation mirrors the moral ambiguity of the plot, making the viewer question what is right and wrong, and who is in control. The pacing of the film contributes to its tension, as Welles never allows the audience to feel fully at ease.

Sound and Music

Welles’ use of sound in Touch of Evil is groundbreaking, much like his work in earlier films. He manipulates sound design to create an immersive and sometimes unsettling atmosphere. Often, diegetic sounds—sounds originating from the environment, like street noises or music from a jukebox—overlap with dialogue, creating a chaotic soundscape that mirrors the confusion of the characters.

- Ambient Sound: In scenes set on the border or in the town’s streets, Welles lets the ambient sound play a key role. The noise of the border town, including crowds, vehicles, and music, contributes to a feeling of constant unrest and tension. Welles also uses silence effectively, letting moments of quiet intensify the drama, especially during confrontations between Quinlan and Vargas.

- Henry Mancini's Score: The score by Henry Mancini complements Welles’ direction by mixing jazz and Latin influences, giving the film a rhythmic, pulsating energy. Mancini’s music underlines the seedy, dangerous atmosphere of the town and heightens the tension in key moments. Welles’ collaboration with Mancini creates a fusion of sound and visuals that feels both immersive and unsettling.

Innovative Blocking and Staging

Welles was known for his unique approach to blocking—how characters move and are positioned in the frame. In Touch of Evil, he stages scenes with dynamic movement, allowing characters to occupy different planes of action within the same frame. This technique gives scenes an almost theatrical quality, with multiple layers of action occurring at once, and reflects Welles’ background in theater.

For example, in scenes involving confrontations, such as between Quinlan and Vargas, Welles blocks the actors in ways that emphasize power dynamics. Quinlan often looms large in the foreground while Vargas appears smaller or at a distance, underscoring the imbalance in their conflict.

Performance Direction

Welles’ direction of actors is another standout element of Touch of Evil. His own performance as Quinlan is full of nuance, transforming the character from a simple antagonist into a deeply flawed human being. Welles encourages his cast to embrace the heightened emotional stakes of the story without resorting to melodrama.

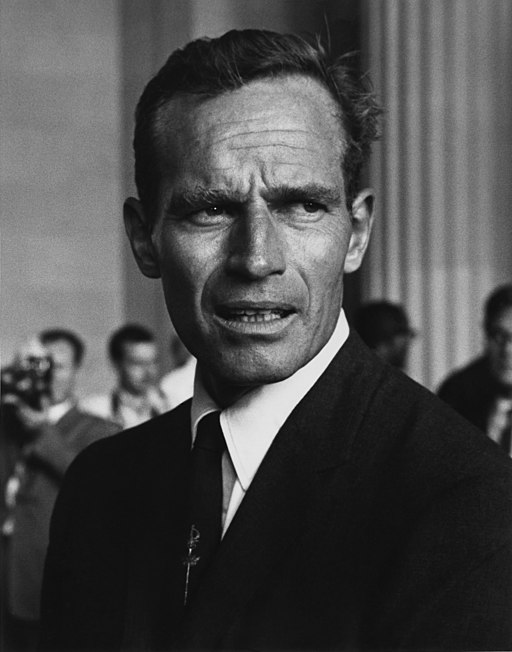

- Charlton Heston as Vargas: Welles draws a more restrained performance from Charlton Heston, who plays Vargas as a figure of righteousness but also of moral rigidity. Welles allows moments where Vargas's fear and frustration surface, humanizing a character who could otherwise seem overly virtuous.

- Supporting Cast: Welles also brings out memorable performances from his supporting cast, including Joseph Calleia as Pete Menzies, whose loyalty to Quinlan slowly crumbles, and Marlene Dietrich as Tanya, whose role, though small, leaves a lasting impact on the film’s tone and its thematic depth.

Moral Ambiguity and Thematic Depth

Welles’ direction in Touch of Evil explores the gray areas of morality and justice. The line between good and evil is constantly blurred, and Welles uses every directorial tool at his disposal to underline this ambiguity. Quinlan, the corrupted cop, believes in his own form of justice, even though it involves planting evidence. Vargas, who stands for law and order, is almost single-minded in his pursuit of Quinlan, to the point that he overlooks the danger posed to his wife. This moral complexity is the core of Welles' vision.

Analysis of Charlton Heston’s Performance

Charlton Heston’s performance in Touch of Evil is an interesting case, as it departs from the type of roles for which he was most famous. Known primarily for playing larger-than-life, heroic figures in films like Ben-Hur and The Ten Commandments, Heston takes on the role of Ramon Miguel "Mike" Vargas, a Mexican narcotics officer, in a much more subdued and morally complex performance. Heston's portrayal of Vargas provides an anchor for the film's exploration of justice and corruption, though it is not without controversy due to his casting as a Mexican character.

Portrayal of Moral Integrity

Heston plays Vargas as a character of unyielding moral integrity. From the beginning, Vargas is shown as an upright man of the law, determined to uphold justice regardless of the personal costs. Heston’s physical presence—tall, stoic, and commanding—gives Vargas an aura of authority and seriousness, which contrasts with the corrupt, decaying figures around him, particularly Captain Quinlan (played by Orson Welles).

- Seriousness and Determination: Throughout the film, Heston maintains an intense focus in his performance. His eyes are often sharp and unwavering, conveying Vargas’ singular determination to uncover the truth behind Quinlan’s corrupt practices. He delivers his lines in a precise, almost clipped manner, reflecting his character’s commitment to justice and his refusal to be swayed by Quinlan’s intimidation tactics or the town’s general atmosphere of moral laxity.

- Rigidity vs. Vulnerability: While Vargas is portrayed as morally rigid, Heston subtly conveys moments of vulnerability, particularly in relation to his wife, Susan (Janet Leigh). As the film progresses and Susan becomes endangered, Heston shifts from the calm, controlled demeanor of an investigator to a more desperate and emotional husband. These moments of emotional intensity reveal a more human side to Vargas, as he struggles to balance his professional duty with his personal concerns. Heston’s performance here is effective in showing that, beneath Vargas’ strong exterior, there is genuine fear and love for his wife, giving the character more depth than initially apparent.

Cultural Sensitivity and Casting Controversy

One of the most debated aspects of Heston’s performance is his casting as a Mexican character. While Heston does not play Vargas with any exaggerated or stereotypical traits, the fact that a white actor was cast to play a Mexican lawman in dark makeup is problematic by modern standards. However, Heston approaches the role with respect, and his performance does not lean on ethnic caricature or over-accentuation.

- Accent and Demeanor: Heston’s attempt at a Mexican accent is subtle, and he avoids overly theatrical flourishes in his speech. Instead of focusing on Vargas' ethnicity, Heston plays the character as a principled man of the law, whose identity is defined more by his sense of duty than his nationality. The understated accent, while not entirely convincing, allows Heston to focus more on Vargas’ moral struggle rather than ethnic identity.

- Presence and Authority: Heston’s physicality, which often characterized his most iconic roles, works in his favor here. As Vargas, Heston exudes a natural authority that is crucial to the character. Vargas needs to command respect, especially as he is often dismissed or undermined by the American authorities he encounters. Heston’s imposing stature and assertive manner help make Vargas a believable figure of authority, and his ability to stand toe-to-toe with Welles’ Quinlan is essential for the film’s central conflict.

Tension with Welles’ Quinlan

The tension between Vargas and Quinlan drives much of the film, and Heston’s performance plays an important role in establishing this dynamic. Where Welles' Quinlan is grotesque, corrupt, and larger-than-life, Heston’s Vargas is clean-cut, honorable, and focused. The two characters represent opposite ends of the moral spectrum, and the contrast between them is reflected in their performances.

- Moral Confrontation: In their confrontations, Heston’s Vargas rarely loses his composure, even when Quinlan tries to intimidate him. Heston plays Vargas with a quiet strength; he doesn’t need to raise his voice to make his presence felt. In the scenes where Vargas accuses Quinlan of planting evidence, Heston conveys a controlled intensity, as if Vargas is trying to keep his frustration in check while still asserting his authority. This contrasts with Welles, who plays Quinlan as a man slowly unraveling, and the interplay between these performances highlights the differences between their characters.

- Physicality and Power Dynamics: Heston’s tall, broad frame is used to suggest the character’s inner strength, but also to emphasize his outsider status. He is often seen as towering over his environment or standing apart from the other characters, underscoring how he doesn’t quite belong in the corrupt, morally decayed world of the border town. His physical stature also becomes a point of tension, particularly in his confrontations with Quinlan. Where Quinlan is depicted as bloated and physically deteriorating, Heston’s Vargas appears in stark contrast, embodying the righteous power of the law. This physical dynamic enhances the film’s central moral conflict.

Relationship with Susan (Janet Leigh)

Heston’s performance is not just about his pursuit of justice; it also reflects his protective instincts toward his wife, Susan. His interactions with her reveal a softer, more personal side to the character. While much of the film focuses on Vargas’ investigation and clashes with Quinlan, the subplot involving Susan’s endangerment allows Heston to show a more emotional, vulnerable side of Vargas.

- Subdued Tenderness: In his scenes with Janet Leigh, Heston softens his otherwise serious demeanor. While still formal in his approach, he demonstrates a genuine concern for Susan, and there are moments of tenderness that break through his professional facade. This is particularly important, as it shows that Vargas, while deeply committed to his job, is not entirely defined by it. Heston’s ability to shift between stoic lawman and concerned husband adds complexity to Vargas’ character.

- Desperation and Guilt: As Susan becomes increasingly ensnared in the town’s corruption, Heston conveys a growing sense of desperation. He realizes that his pursuit of Quinlan has made his wife a target, and this realization adds an emotional weight to his character arc. Heston plays these moments with a subdued sense of guilt and frustration, as Vargas tries to balance his sense of duty with his responsibility to protect his wife.

Moral Idealism vs. Realism

Heston’s Vargas is the embodiment of moral idealism, and Heston plays him with an unwavering sense of righteousness. However, as the film progresses, it becomes clear that Vargas’ idealism puts him at odds with the gritty, morally ambiguous world he is trying to navigate. Heston’s performance reflects this tension, as Vargas, despite his best efforts, is constantly thwarted by the systemic corruption that surrounds him.

- Persistence and Frustration: Heston’s portrayal of Vargas as a man who refuses to compromise his values even when faced with overwhelming corruption makes his performance stand out. He shows Vargas as a character who is steadfast in his belief in the law, but at the same time, he subtly conveys the frustration of trying to uphold justice in a world that is deeply corrupt. This gives Vargas a sense of tragic heroism—he’s a man who believes in doing the right thing, but his moral purity makes him vulnerable in a town where such values are seen as weaknesses.

Conclusion

Charlton Heston’s performance as Mike Vargas in Touch of Evil is defined by his portrayal of unwavering moral righteousness in a world steeped in corruption. His stoic, commanding presence and intense focus on justice make Vargas an intriguing and noble character, though his rigid sense of duty sometimes blinds him to the personal consequences of his actions. While Heston’s casting as a Mexican character is controversial, his respectful and earnest approach to the role focuses on the character’s moral strength rather than relying on ethnic stereotypes.

In the larger context of the film, Heston’s Vargas serves as a moral counterpoint to Orson Welles’ corrupt and decaying Quinlan, and his performance helps anchor the film’s exploration of justice, corruption, and the gray areas in between. Heston effectively portrays a character caught between his ideals and the harsh realities of a morally compromised world, making his performance a crucial part of the film’s tension and thematic depth.

Memorable Quotes from the Movie

Tanya (Marlene Dietrich):

- "He was some kind of a man. What does it matter what you say about people?"

This quote is spoken by Tanya after Quinlan's death, serving as a poignant and cryptic epitaph. It reflects the film's overall theme of moral ambiguity, suggesting that human complexity transcends simplistic judgments of good or evil.

Captain Hank Quinlan (Orson Welles):

- "I don’t drink—when I’m on duty."

Quinlan says this ironically as his drinking problem worsens throughout the film, symbolizing his descent into corruption and decay.

- "Come on, read my future for me. You haven’t got any. Your future’s all used up."

Quinlan says this to Tanya, but it also serves as a reflection of his own fate. It underscores Quinlan’s awareness of his own moral and physical deterioration, hinting at the tragic inevitability of his downfall.

Mike Vargas (Charlton Heston):

- "A policeman's job is only easy in a police state."

Vargas speaks this line when discussing Quinlan's corrupt methods. It reflects his belief in the rule of law and serves as a critique of Quinlan's authoritarian approach to justice, where evidence is manipulated to secure convictions.

- "All border towns bring out the worst in a country."

This line by Vargas emphasizes the corrupt and morally decayed nature of the film's setting. It highlights the themes of blurred boundaries—both literal and moral—that run throughout the film.

Pete Menzies (Joseph Calleia):

- "That’s the second bullet I stopped for you."

Menzies says this to Quinlan in the final scene after being fatally wounded. It’s a tragic reminder of Menzies’ loyalty to Quinlan, despite his growing realization that his mentor has become corrupt.

Susan Vargas (Janet Leigh):

- "He said he didn’t want to think of me. He wanted to remember me."

Susan says this after being frightened by her encounters in the border town. The line reflects her vulnerability and hints at the threats she faces in this morally ambiguous environment.

"Uncle" Joe Grandi (Akim Tamiroff):

- "Big cops have big appetites."

Grandi says this in reference to Quinlan, capturing the idea that Quinlan’s corruption is not only moral but also physical. The quote adds to the imagery of Quinlan as a bloated figure consumed by his own vices.

Tanya (Marlene Dietrich):

- "Your future is all used up."

Tanya’s repeated line to Quinlan foreshadows his inevitable demise, echoing the theme of a man who has outlived his own sense of morality and purpose.

Classic Scenes from the Movie

The Opening Tracking Shot

- Why it’s iconic: The film begins with one of the most celebrated shots in cinema history: a continuous, unbroken tracking shot lasting more than three minutes. It follows a car rigged with a time bomb as it drives through a bustling Mexican border town. As the camera tracks the car, we also see Ramon Miguel Vargas (Charlton Heston) and his wife, Susan (Janet Leigh), as they stroll toward the U.S. border. The tension builds as the audience knows the bomb is about to explode, but the characters remain oblivious. The car finally crosses the border and explodes just after passing through customs, setting off the central investigation of the plot.

- Why it matters: This shot is celebrated for its technical achievement, using a single take to establish the tone, setting, and tension of the film. It pulls the viewer immediately into the story and shows Welles’ mastery of complex, choreographed scenes. The long take draws attention to the contrasts in the border town, mixing ordinary life with the constant threat of danger.

Quinlan’s First Appearance

- Why it’s iconic: The introduction of Captain Hank Quinlan (Orson Welles) is memorable because of the way Welles emphasizes his grotesque, imposing presence. When Quinlan arrives at the crime scene, the camera tilts upward from his feet to his massive, disheveled body, giving him an almost monstrous appearance. His presence immediately commands attention, and it’s clear from the beginning that Quinlan is a corrupt but powerful figure in the town.

- Why it matters: This scene establishes Quinlan as the film’s dominant and morally decayed character. Welles’ physical transformation—he wears padding to appear overweight, and his face is heavily made-up—adds to the sense that Quinlan is a man who has succumbed to years of moral and physical corruption. The way the camera angles emphasize his size and weight shows how his influence looms over everyone in the town.

The Motel Scene (Susan’s Ordeal)

- Why it’s iconic: One of the most terrifying and intense sequences in Touch of Evil is the motel scene, where Susan Vargas is terrorized and eventually drugged by Grandi’s gang. This scene is claustrophobic, filled with mounting tension as Susan becomes increasingly isolated. Dennis Weaver’s unsettling portrayal of the motel night manager only adds to the creepiness of the scene. It culminates in Susan being overpowered and left unconscious, setting the stage for her being framed for drug use.

- Why it matters: This scene is notable for its suspense and the way Welles manipulates space to create a sense of isolation and danger. The motel’s remote location emphasizes Susan’s vulnerability, and Welles uses deep shadows and close-ups to heighten the feeling of claustrophobia. This scene underscores the film’s themes of powerlessness and victimization, especially for Susan, who becomes a pawn in the larger conflict between Quinlan and Vargas.

The Confession Scene (Quinlan and Menzies)

- Why it’s iconic: In this pivotal scene, Vargas convinces Pete Menzies (Joseph Calleia) to wear a hidden microphone to record Quinlan’s confession. As Quinlan and Menzies walk near the canal, the tension mounts as Quinlan begins to realize he’s being betrayed. Quinlan drunkenly reflects on his past crimes and justifies his corrupt actions, making it clear that he sees himself as a necessary evil to keep order. When Quinlan finally discovers Menzies’ betrayal, he kills him, and a dramatic confrontation with Vargas ensues.

- Why it matters: This scene is a culmination of the moral conflict that drives the film. It reveals Quinlan’s deeply flawed justification for his corrupt methods, showing him as a tragic figure who believes in his own version of justice. The scene is masterfully directed, with Welles using shadows, reflections, and the eerie sound of Quinlan’s confession echoing across the canal to create a sense of inevitability and doom. The canal setting also adds a layer of symbolism—Quinlan’s fall into the dirty, polluted water mirrors his moral decline.

Tanya’s Final Words

- Why it’s iconic: In the film’s closing moments, after Quinlan has been killed, Vargas speaks with Tanya (Marlene Dietrich), an old friend of Quinlan’s. When Vargas asks if she knew Quinlan had been a great man, Tanya replies, “He was some kind of a man. What does it matter what you say about people?” This line is both cryptic and profound, leaving the audience to reflect on the complexity of Quinlan’s character.

- Why it matters: Tanya’s line encapsulates one of the central themes of the film: the moral ambiguity of people and their actions. It suggests that the judgment of Quinlan’s life is ultimately futile because people are complicated, and the lines between good and evil are blurred. Her indifference also reflects the film’s dark, noir worldview, where morality is subjective, and the truth is often murky.

Quinlan and Tanya’s Reunion

- Why it’s iconic: Earlier in the film, Quinlan visits Tanya at her fortune-telling parlor, where they share a melancholic conversation about their past. Quinlan is clearly seeking solace, but Tanya remains detached. She delivers the memorable line, “Your future’s all used up,” a fatalistic statement that foreshadows Quinlan’s downfall.

- Why it matters: This scene reveals a more vulnerable side of Quinlan. Despite his corruption, he is a man haunted by his past, seeking some form of redemption or at least comfort. Tanya’s indifference toward Quinlan shows that she has already come to terms with his inevitable fate, underscoring the film’s themes of inevitability and moral decay.

The Planting of Evidence

- Why it’s iconic: Early in the film, Quinlan and Vargas investigate the apartment of Manolo Sanchez, the man accused of planting the bomb. As Vargas watches, Quinlan “finds” two sticks of dynamite, which he has clearly planted to frame Sanchez. Vargas realizes that Quinlan has been using this method of planting evidence for years to close cases.

- Why it matters: This scene is crucial in establishing Quinlan’s corrupt practices and setting up the conflict between him and Vargas. It raises questions about justice and whether the ends justify the means. For Quinlan, it’s more important to get a conviction than to follow the law. This moment also catalyzes Vargas’s investigation into Quinlan’s history of corruption.

Awards and Recognition

Touch of Evil (1958) was not widely recognized by major award bodies at the time of its release, partly because it was poorly handled by the studio and had a limited release. However, over the years, it has become a highly respected film, particularly in critical and scholarly circles. The movie didn’t receive many awards upon its initial release, but it has earned accolades in retrospectives, restorations, and film history rankings since then.

Here is an overview of notable recognitions related to the film:

- National Film Preservation Board (USA)

In 1993, Touch of Evil was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."

- Cahiers du Cinéma

French critics, particularly those associated with Cahiers du Cinéma, championed the film early on, recognizing Orson Welles’ innovative direction and declaring Touch of Evil a masterpiece of film noir.

- Online Film & Television Association Awards (1998)

Winner: OFTA Film Hall of Fame (Motion Picture)

This recognition came as part of a retrospective celebration of the film’s importance in cinema history.

Critical Acclaim in Retrospective Rankings:

While the film did not garner many awards upon its release, it has been consistently included in "Best of" lists in subsequent decades, showing its lasting impact on film history. Some of the notable rankings include:

- Sight & Sound Critics' Poll (1992, 2002, 2012)

The film has ranked highly in various iterations of the prestigious Sight & Sound poll, often regarded as one of the most important film polls in the world. In 2012, it was ranked as the 57th greatest film of all time by critics.

- American Film Institute (AFI)

Touch of Evil is frequently included in AFI’s lists of the greatest American films, particularly in the genre of film noir.

AFI's 100 Years…100 Thrills (2001) ranked Touch of Evil #64 on its list of the most thrilling American films.

- Directors Guild of America (DGA)

While it didn’t win awards from the DGA during its release, Orson Welles' direction in Touch of Evil has been praised as one of the most influential in cinema history.

- Berlin International Film Festival (Restored Version, 1998)

Touch of Evil was re-released with a restored version based on Orson Welles' original notes in 1998, and it was shown at the Berlin International Film Festival, where it garnered widespread acclaim from contemporary critics.

Restored Version (1998)

The film's re-evaluation, especially with the 1998 re-release of the restored version, brought new critical acclaim, though it didn’t lead to a sweep of traditional awards at that time. The restored version is considered a definitive presentation of Welles' vision and has received much praise from film historians and critics alike.