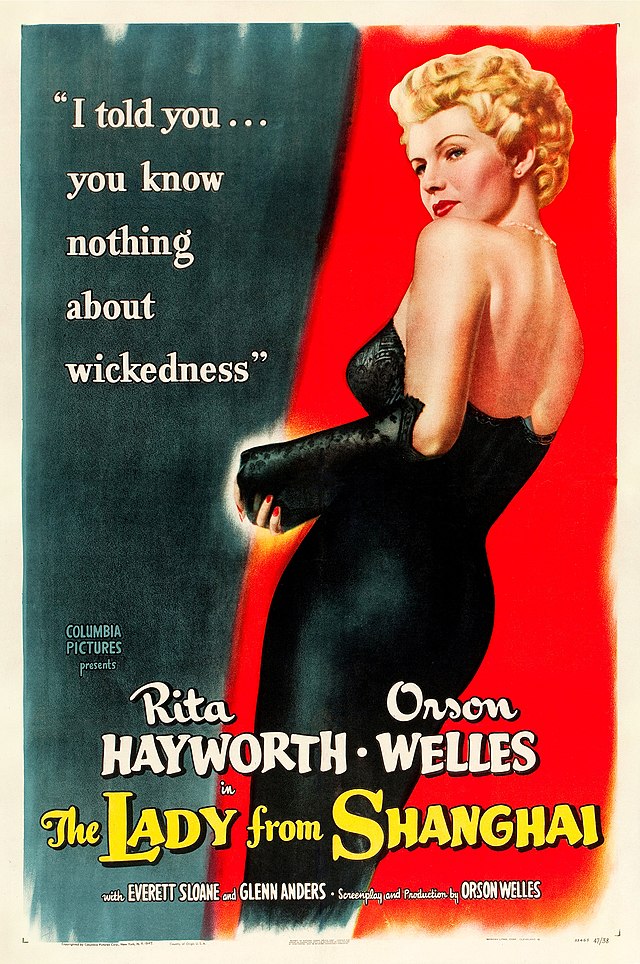

The Lady from Shanghai - 1947

back| Released by | Columbia Pictures |

| Director | Orson Welles |

| Producer | Orson Welles |

| Script | Orson Welles, based on the novel If I Die Before I Wake by Sherwood King |

| Cinematography | Charles Lawton Jr. |

| Music by | Heinz Roemheld |

| Running time | 87 minutes |

| Film budget | $2 million |

| Box office sales | $2.3 million |

| Main cast | Orson Welles - Rita Hayworth - Everett Sloane - Glenn Anders - Ted de Corsia |

The Lady from Shanghai

An Underestimated Classic Film Noir

The Lady from Shanghai (1947), directed by Orson Welles, is a classic film noir that weaves a tale of deception, betrayal, and moral ambiguity.

It follows Irish seaman Michael O’Hara (Welles), who becomes entangled with the mysterious Elsa Bannister (Rita Hayworth) and her corrupt lawyer husband in a deadly murder scheme. The film’s visual style is iconic, with its famous hall of mirrors climax symbolizing the fractured identities and deceptions of its characters.

Related

The Lady from Shanghai – 1947

Summary of The Lady from Shanghai (1947)

The Lady from Shanghai is a complex film noir that blends mystery, romance, and betrayal, set against a backdrop of shadowy corruption and intrigue. Directed by Orson Welles, the film follows Michael O'Hara (played by Welles himself), an Irish seaman who becomes entangled in a web of deceit and murder when he crosses paths with the alluring Elsa Bannister (Rita Hayworth). The film is notable for its dreamlike quality, visual style, and the disorienting, morally ambiguous world it portrays.

The story begins when Michael, a drifter and romantic, impulsively saves Elsa from a gang of attackers in New York’s Central Park. Captivated by her beauty, he agrees to work as a crew member on her husband's yacht. Elsa's husband, Arthur Bannister (Everett Sloane), is a renowned but unscrupulous criminal defense attorney. Michael soon finds himself aboard the yacht, sailing from New York to San Francisco, along with Arthur and his business partner, the eccentric and unsettling George Grisby (Glenn Anders).

As they sail down the coast of Mexico, tensions build between the characters. Michael is increasingly drawn to Elsa, who seems trapped in a loveless marriage. Despite knowing the danger of getting involved with her, Michael falls in love. Arthur, meanwhile, appears indifferent or perhaps resigned to his wife’s flirtations, as if he too is playing a long, twisted game.

The plot thickens when Grisby approaches Michael with an odd proposition: Grisby wants Michael to "murder" him, though in reality, he has no intention of dying. Grisby plans to fake his own death to collect the insurance money and offers Michael $5,000 for the job, promising there will be no consequences since a corpse will never be found. Desperate for money and convinced of the scheme’s absurdity, Michael agrees to the plan.

However, things quickly spiral out of control. Grisby is actually killed, though not by Michael. Michael is framed for the murder, setting off a series of events that spiral into a dark, surreal nightmare. He stands trial, with Arthur Bannister serving as his defense attorney, creating an uncomfortable tension as the same man whose wife Michael loves tries to save him from a death sentence. Throughout the trial, the truth becomes increasingly unclear, as layers of deception are peeled away.

The climax of the film unfolds in the iconic "hall of mirrors" sequence in San Francisco’s Chinatown. Here, the characters confront their own distorted reflections, both literal and metaphorical. Elsa reveals her complicity in the crime, and a fatal shootout occurs, with Bannister and Elsa both dying in the confusion. Michael, disillusioned and weary, walks away from the shattered remains of the Bannister’s world, leaving behind the treacherous life that almost consumed him.

Analysis

The Lady from Shanghai is a film that defies easy categorization. On the surface, it adheres to many conventions of the film noir genre: a morally ambiguous protagonist, a femme fatale, and a plot revolving around deception, murder, and betrayal. But Orson Welles infuses the film with a unique style and tone, creating a work that feels both mysterious and dreamlike, often disorienting viewers with its fragmented narrative and visual flair.

Themes of Betrayal and Moral Ambiguity

At the heart of The Lady from Shanghai is a tangled web of betrayal. Every major character has something to hide, and no one is entirely trustworthy. Elsa Bannister embodies the classic femme fatale, luring Michael into a deadly trap with her beauty and false vulnerability. She plays a central role in the deception that unfolds, yet Welles also presents her as a tragic figure—caught in her own web, her motives for survival leading her to destroy herself and those around her.

The character of Michael O'Hara is similarly complex. He begins the film as an idealistic, romantic figure, believing in love and adventure. However, by the end, he has been irrevocably altered, his innocence shattered by the manipulations of those around him. His journey mirrors that of many noir protagonists: seduced by a dangerous woman, he becomes ensnared in a plot beyond his control, ultimately learning that the world is far more cynical and corrupt than he ever imagined.

Visual Style and Cinematic Innovation

Visually, The Lady from Shanghai is one of Welles’ most daring films. The cinematography, by Charles Lawton Jr., is filled with striking compositions, deep shadows, and distorted perspectives that reflect the fractured relationships and skewed moral landscape of the story. The use of low angles, extreme close-ups, and disorienting camera angles contributes to a sense of unease throughout the film. Welles employs a number of innovative techniques to heighten the tension and give the film its surreal, dreamlike quality.

The film’s most famous sequence—the climax in the hall of mirrors—is a masterclass in visual storytelling. Here, Welles uses reflections to multiply the characters, creating a literal labyrinth where identities blur and truths are shattered. The mirrors serve as a metaphor for the characters' fractured psyches, their true selves obscured by layers of deception. This scene has become iconic in cinema history, influencing countless films and directors in its wake.

Social Commentary

While the plot of The Lady from Shanghai focuses on personal betrayal and crime, there are undercurrents of social commentary running throughout the film. The character of Arthur Bannister, the corrupt defense attorney, represents the moral decay of the elite. His wealth and power shield him from consequences, allowing him to manipulate others with impunity. Bannister’s physical frailty (he walks with canes) contrasts sharply with his cunning and ruthlessness, making him a figure of both pity and fear.

The film also explores themes of entrapment and disillusionment. Elsa is trapped in her marriage to Bannister, while Michael is trapped by his own desires and the schemes of those around him. These characters move through a world where love and loyalty are illusions, and where survival often depends on how well one can deceive others.

Legacy and Impact

The Lady from Shanghai was not well-received upon its initial release, partly due to the studio’s interference with the final cut. Columbia Pictures heavily edited Welles’ original vision, cutting more than an hour from the film and altering its structure. However, over time, the film has gained recognition as one of Welles’ most innovative works, particularly for its bold visual style and psychological complexity.

Today, The Lady from Shanghai is regarded as a classic of film noir, praised for its atmosphere, intricate plotting, and groundbreaking use of imagery. Its themes of moral ambiguity, betrayal, and corruption continue to resonate with audiences, while its visual flourishes remain influential in the world of cinema.

Conclusion

The Lady from Shanghai is a quintessential film noir, rich with atmosphere, moral complexity, and visual innovation. Orson Welles crafted a disorienting and layered tale of lust, greed, and betrayal, anchored by a powerful performance from Rita Hayworth as the enigmatic Elsa. Though initially misunderstood, the film has earned its place as a masterpiece of 20th-century cinema, a haunting exploration of the darker aspects of human nature.

Full Cast

· Orson Welles as Michael O'Hara

· Rita Hayworth as Elsa Bannister

· Everett Sloane as Arthur Bannister

· Glenn Anders as George Grisby

· Ted de Corsia as Sidney Broome

· Erskine Sanford as Judge

· Gus Schilling as Goldie

· Carl Frank as District Attorney Galloway

· Louis Merrill as Jake

· Evelyn Ellis as Bessie

· Harry Shannon as Cab Driver

· Byron Kane as Reporter

· Frank Sully as Detective

Masterful Direction of Orson Welles

Orson Welles' direction in The Lady from Shanghai is a masterclass in cinematic innovation, blending visual experimentation with a deep exploration of character psychology and themes of moral ambiguity. His approach to this film—marked by bold stylistic choices, narrative complexity, and an atmosphere of disorientation—showcases Welles' distinctive vision and storytelling prowess.

Visual Storytelling and Experimentation

One of the most striking aspects of Welles' direction in The Lady from Shanghai is his adventurous use of visual techniques to create mood, tension, and thematic depth. Welles was known for pushing the boundaries of conventional filmmaking, and this film is no exception. He employed extreme camera angles, deep shadows, and distorted perspectives to reflect the psychological turmoil of the characters. The disorienting angles, particularly in scenes like the climactic courtroom sequence and the iconic hall of mirrors finale, serve to heighten the sense of paranoia and confusion that pervades the film.

Welles was also a master of creating visual contrast, using both light and dark to symbolize the moral ambiguity that defines the characters. The film’s noir atmosphere is heavily influenced by its use of stark lighting and shadow, giving the film a surreal, dreamlike quality. For example, Welles often positions characters in half-light, visually suggesting their hidden motivations and the murky morality that runs through the narrative. These techniques make the film visually compelling and emphasize the sense of entrapment experienced by the characters.

The famous "hall of mirrors" sequence is perhaps the pinnacle of Welles’ visual experimentation in the film. This scene, in which the characters confront each other amidst countless reflections, is not just an action-packed climax but also a metaphor for the fractured identities and deceptive nature of those involved. Welles transforms a simple shootout into a visually complex, almost abstract sequence that reflects the larger themes of the film: illusion, betrayal, and the multiplicity of human desires. By disorienting the audience with reflections upon reflections, Welles forces viewers to question what is real and who can be trusted—a core element of film noir.

Narrative Complexity and Subversion

Welles' direction in The Lady from Shanghai is notable for its subversion of traditional noir elements. Although it includes many of the standard tropes of the genre—such as the femme fatale, the morally conflicted hero, and a plot centered around crime and deception—Welles layers the story with a surreal, almost absurdist tone. He intentionally leaves certain aspects of the plot vague or unresolved, creating an atmosphere of uncertainty and chaos that reflects the moral murkiness of the world in which the characters operate.

Throughout the film, Welles plays with audience expectations. Michael O'Hara, played by Welles himself, is introduced as the film’s protagonist, yet he is less the traditional noir hero and more of a pawn in the schemes of others. While he narrates the story, his voiceover is often ambiguous, and his decision-making feels both impulsive and confused, mirroring the audience's growing sense of disorientation. By positioning the viewer alongside O'Hara—often unsure of what’s happening or why—Welles deepens the psychological complexity of the film and subverts the more linear storytelling of conventional noirs.

This lack of clarity is part of Welles' deliberate strategy. In true Wellesian fashion, he doesn’t offer easy answers, leaving the audience to interpret the motivations of characters like Elsa Bannister (Rita Hayworth) and Arthur Bannister (Everett Sloane) without fully understanding their intentions. The characters’ shifting loyalties and hidden motives create a puzzle that reflects Welles’ fascination with ambiguity, both moral and narrative. It is a film that encourages rewatching, as the seemingly chaotic events gradually reveal a deeper, more layered meaning upon further reflection.

Control Over Atmosphere and Tone

Welles’ mastery of atmosphere is another key feature of his direction. From the very beginning of the film, there is a pervasive sense of doom and fatalism, which defines much of the film’s tone. The film’s opening sequence in Central Park, where Michael saves Elsa from a group of attackers, sets the stage for the murky morality that will follow. Even this act of heroism is tinged with a sense of foreboding, as if Michael is being drawn into a world of deceit and danger that he cannot fully understand.

Throughout the film, Welles balances moments of slow, deliberate pacing with sudden bursts of action or revelation, keeping the audience in a constant state of unease. For example, the leisurely scenes aboard the yacht—filled with the sparkling waters of Mexico—are juxtaposed with darker, more claustrophobic moments of confrontation and tension. The use of contrasting environments (open seas versus narrow courtrooms or the mirror-filled funhouse) adds to the film's complex and shifting tone, evoking both the freedom and entrapment of the characters.

The tone of The Lady from Shanghai is further shaped by Welles’ integration of dark humor and surreal touches. Scenes like Grisby’s bizarre, almost nonsensical proposition to Michael (to be "murdered" but survive) reveal Welles’ affinity for blending absurdity with suspense. There’s a dreamlike, almost Kafkaesque quality to certain parts of the film, especially the trial, where O'Hara’s fate is in the hands of the very man who despises him—Arthur Bannister. Welles’ ability to blend such a wide array of moods—romance, dread, comedy, and tragedy—demonstrates his skill in shaping the film’s overall tone and atmosphere.

Use of Actors and Performances

Welles' direction of actors in The Lady from Shanghai was also distinctive. He coaxed nuanced performances from his cast, particularly Rita Hayworth, whom he transformed from her typical glamorous screen persona into a more complex, dangerous figure. Hayworth’s portrayal of Elsa Bannister is layered and enigmatic, a femme fatale who isn’t simply an object of desire but a morally ambiguous character who manipulates those around her to achieve her own ends.

Welles' own performance as Michael O'Hara is notable for its understated quality. Rather than playing a confident, sharp-edged noir hero, Welles presents O'Hara as somewhat naïve, confused, and emotionally vulnerable. This contrasts with his earlier roles in films like Citizen Kane or The Third Man, where he plays more assertive or charismatic figures. In The Lady from Shanghai, O'Hara's vulnerability makes him a compelling but flawed protagonist—an everyman caught up in forces beyond his control.

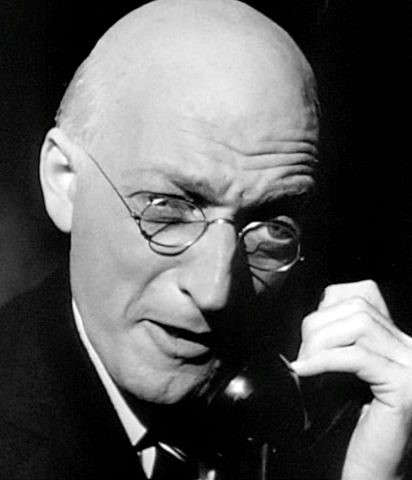

Everett Sloane’s portrayal of the crippled but menacing Arthur Bannister is another key element of Welles’ direction. Bannister’s physical weakness contrasts sharply with his intellectual and emotional dominance. Welles uses Bannister's disability not as a source of pity but as a symbol of his moral corruption and his controlling, manipulative nature. In scenes where Bannister's voice is calm and measured, there’s an underlying sense of menace, revealing Welles' keen ability to direct subtle, layered performances.

Conclusion: Welles' Auteur Vision

Overall, Orson Welles’ direction of The Lady from Shanghai is a blend of bold visual style, psychological depth, and narrative complexity. His willingness to challenge genre conventions and subvert expectations gives the film a timeless, enigmatic quality. Welles’ auteur vision permeates every aspect of the film, from its disorienting cinematography to its exploration of identity and morality, making The Lady from Shanghai a fascinating and enduring piece of cinematic art. Though not fully appreciated during its initial release, the film has since been recognized as a bold and innovative work, showcasing Welles’ mastery as a director and his commitment to pushing the boundaries of filmmaking.

Stellar Performance of Rita Hayworth

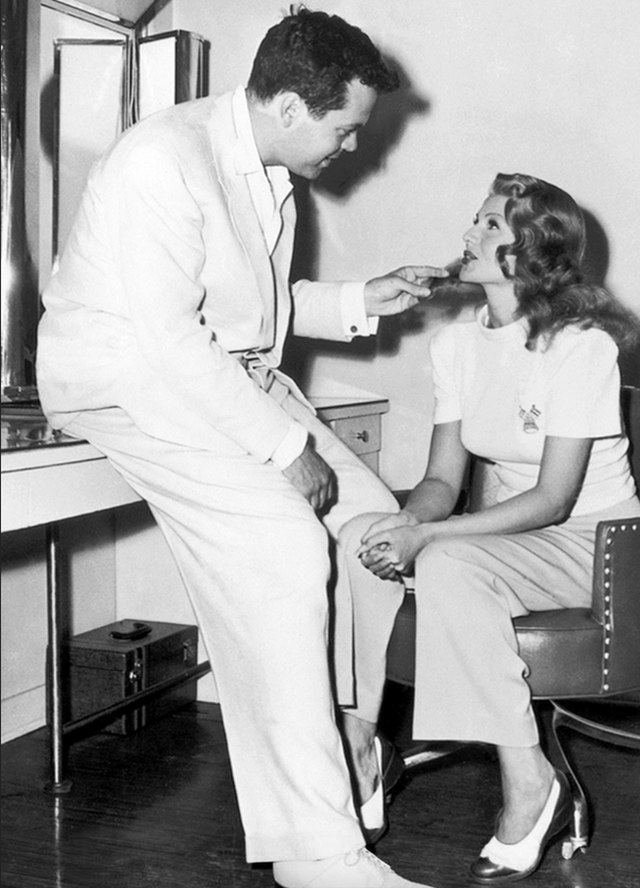

Rita Hayworth’s performance in The Lady from Shanghai is a powerful departure from her typical screen roles, showcasing a complex and multifaceted portrayal of the classic femme fatale, Elsa Bannister. Under the direction of her then-husband Orson Welles, Hayworth transformed from her usual glamorous image into a darker, more enigmatic character, revealing her versatility as an actress.

Reinvention of Rita Hayworth’s Persona

Prior to The Lady from Shanghai, Rita Hayworth was known primarily as a glamorous, seductive figure, often cast in roles that emphasized her physical beauty and charisma, such as her iconic performance in Gilda (1946). However, in this film, Welles deliberately subverts her established image. Most notably, he directed her to cut and bleach her famous long red hair into a striking platinum blonde bob, transforming her into a colder, more ethereal presence. This visual change signaled a deeper transformation in Hayworth’s performance, as she embodied a character who was far more ambiguous and morally complex than her previous roles.

As Elsa Bannister, Hayworth brings a sense of mystery and danger that is essential to the femme fatale archetype. She portrays Elsa as a woman who is both seductive and vulnerable, leading the audience and the protagonist, Michael O'Hara, to question her true motives throughout the film. Hayworth plays Elsa with a subtle sense of duality: on the surface, she appears to be a helpless, trapped woman, but underneath, she harbors dangerous secrets and manipulative tendencies. Her ability to balance this contrast in her performance is key to the character’s allure and the film’s tension.

Complexity and Ambiguity in Elsa Bannister

One of the most remarkable aspects of Hayworth’s performance is her ability to convey Elsa’s complexity through understated gestures and expressions. While her character is often soft-spoken and seemingly passive, there is always an undercurrent of tension and calculation behind her actions. Hayworth uses her eyes and body language to suggest that Elsa is constantly assessing the people around her, weighing her options, and deciding how best to use her charms to manipulate others to her advantage. This subtle approach makes Elsa a far more intriguing character than a typical femme fatale, as her motivations remain opaque for much of the film.

Throughout The Lady from Shanghai, Elsa Bannister oscillates between being the victim and the villain, and Hayworth navigates these shifts with a sense of restraint and nuance. At times, Elsa appears genuinely vulnerable, especially in her scenes with Michael O'Hara. Hayworth brings an air of sadness and desperation to these moments, making it seem as though Elsa is a woman trapped in a loveless marriage with her cruel, controlling husband, Arthur Bannister. Yet even in these scenes, there is a layer of ambiguity—Hayworth never fully allows the audience to trust Elsa’s emotions, leaving open the possibility that she is using her vulnerability as a weapon to ensnare Michael in her schemes.

This ambiguity is central to the character’s power. Elsa is a woman who exists in a morally gray area, and Hayworth’s performance reflects this lack of clarity. Her delivery of lines is often calm and measured, with an almost hypnotic quality that draws the other characters—and the audience—into her web. Even when she confesses her feelings or reveals aspects of her past, there is a cool detachment in her voice, making it difficult to discern whether she is being truthful or manipulating those around her.

Elsa's Seductive Power and Control

In many ways, Hayworth’s portrayal of Elsa Bannister epitomizes the femme fatale’s ability to seduce and control men through her beauty and charm. However, rather than relying solely on her physical appearance, Hayworth brings a psychological depth to Elsa’s seduction. She portrays Elsa as a woman who understands the power of her beauty but uses it strategically, rather than flamboyantly. Elsa's seduction of Michael O'Hara is not overt but subtle, as she lures him into her world with promises of love and escape. Hayworth’s performance in these scenes is almost hypnotic—her calm, measured tone, combined with her distant gaze, suggests a woman who knows she can make men do her bidding without needing to over-exert herself.

This sense of control is especially evident in Hayworth’s interactions with the male characters. Whether she is dealing with her husband, Arthur Bannister, or the unstable George Grisby, Hayworth’s Elsa maintains an air of quiet dominance. In contrast to the men, who are often emotionally volatile or visibly desperate, Elsa is a picture of composure. Even in moments of high tension, such as when her schemes begin to unravel or during the film’s climactic hall of mirrors sequence, Hayworth retains this calmness, reflecting Elsa’s ability to manipulate events and people without losing her sense of self-possession.

Tragic Dimension of Elsa Bannister

Despite her manipulative tendencies, Hayworth also imbues Elsa with a sense of tragedy, making her more than just a villainous figure. Elsa’s backstory, which hints at a life of dissatisfaction and entrapment in her marriage to Arthur Bannister, adds a layer of emotional depth to her character. Hayworth plays Elsa as a woman who is deeply unhappy, even though she possesses wealth and status. Her longing for escape, whether through her affair with Michael or through the dangerous schemes she concocts, gives the character a tragic edge.

Hayworth's performance suggests that Elsa is not purely driven by greed or malice, but by a desperate need to break free from her circumstances. This desperation, combined with her manipulative tendencies, makes her both sympathetic and dangerous. The audience may feel pity for her, even as they recognize her capacity for betrayal. Hayworth’s ability to evoke both sympathy and fear is a testament to her nuanced performance and the complexity she brings to Elsa’s character.

The Hall of Mirrors Sequence: Elsa’s Final Moment

The famous hall of mirrors sequence at the film’s climax is not only a visual highlight but also one of the most significant moments for Hayworth’s character. In this scene, Elsa’s true nature is fully revealed, and Hayworth delivers one of her most powerful performances. As the various reflections of Elsa fill the screen, her carefully constructed facade begins to shatter. The layers of deception that have defined her character throughout the film are symbolically stripped away, leaving her vulnerable and exposed.

Hayworth’s performance in this scene captures the full range of Elsa’s emotions—fear, desperation, and finally resignation. As the mirrors shatter around her, Elsa’s control over the situation crumbles, and Hayworth allows the character’s vulnerability to come to the forefront. In her final moments, Elsa’s tragic dimension becomes fully realized, as she faces the consequences of her own actions. Hayworth’s portrayal in this scene is haunting, as she brings a sense of inevitability to Elsa’s downfall, making her both a victim of her own choices and a figure of tragic consequence.

Conclusion: A Landmark Performance

Rita Hayworth’s portrayal of Elsa Bannister in The Lady from Shanghai is one of the most complex and captivating performances of her career. By subverting her glamorous image and embracing a role that required both emotional depth and psychological ambiguity, Hayworth demonstrated her range as an actress. Her performance as Elsa transcends the traditional femme fatale archetype, offering a character who is as tragic as she is dangerous, as manipulative as she is vulnerable.

Through subtle gestures, a quiet yet commanding presence, and a deep understanding of her character’s motivations, Hayworth brings Elsa Bannister to life in a way that leaves a lasting impression. Her performance is integral to the film’s success and remains one of the most memorable aspects of The Lady from Shanghai, cementing Hayworth’s legacy as an actress capable of great complexity and nuance.

Notable Quotes from the Movie

Michael O’Hara (Orson Welles)

"I told you... you know nothing about wickedness."

Michael says this to Elsa early in the film, foreshadowing the darkness and moral corruption he will encounter as he becomes involved with her and her husband.

"When I start out to make a fool of myself, there’s very little can stop me."

Michael reflects on his impulsive decisions and the way his attraction to Elsa leads him into a dangerous web of lies and murder.

"Killing you is killing myself. But you know, I'm pretty tired of both of us."

This chilling line encapsulates Michael’s despair and disillusionment, as he realizes the toxic, destructive relationship he has with Elsa and the moral decay it has brought into his life.

"The only way to stay out of trouble is to grow old, so old that nothing matters anymore."

Michael’s disillusionment with the world is summed up in this line, showing his cynicism and the sense of inevitability in the downward spiral he finds himself in.

Elsa Bannister (Rita Hayworth)

"You need more than luck in Shanghai."

Elsa’s mysterious warning to Michael reflects the dangers he’s about to face. It also highlights the ambiguity of her character and the unseen forces at play in their relationship.

"It's a bright, guilty world."

Elsa’s line reflects her worldview and the moral ambiguity of the world they inhabit, where guilt and corruption are pervasive, and no one is truly innocent.

George Grisby (Glenn Anders)

"Target practice? That’s crazy. I’m what’s left of a human being after serving as a lawyer for all of these years."

Grisby’s eccentric, unsettling personality shines through in this line, which also hints at his warped view of morality after years of working in corrupt legal circles.

"Would you kill me if I asked you to?"

Grisby’s bizarre request to Michael is the catalyst for the film’s central conflict. The absurdity of this proposition underscores the twisted nature of the characters’ relationships and the dangerous games they play.

Arthur Bannister (Everett Sloane)

"You don't make a living as a lawyer without understanding people. But you understand them better as a murderer."

Bannister’s cynical view of human nature and the law underscores his own moral corruption and manipulative nature. His statement reveals how power and control over others are more important to him than justice or truth.

Other Notable Quotes

"You’ll be caught, and then you’ll hang." – Elsa to Michael

This line highlights the sense of impending doom that pervades the film, as Elsa tries to manipulate Michael while also warning him of the danger he faces.

"I’ll be innocent until I’m found guilty, and besides, it’s all a mistake!" – Michael O'Hara

Michael’s desperate attempt to proclaim his innocence in a world where the truth is elusive and justice is manipulated by those in power.

Iconic Scenes from The Lady from Shanghai

The Lady from Shanghai (1947) contains several iconic and visually innovative scenes that have become classics in the history of cinema. Orson Welles’ direction and storytelling were ahead of their time, and these key scenes highlight the film’s blend of psychological complexity, surreal imagery, and film noir style.

The Hall of Mirrors Finale

Perhaps the most famous scene in the film, and one of the most iconic in cinematic history, the "hall of mirrors" sequence takes place during the film's climactic showdown in a funhouse. The scene visually symbolizes the fragmented identities and deceit that run throughout the film. Welles uses a series of mirrors to create a disorienting environment, multiplying the reflections of Elsa, Arthur, and Michael to the point where it becomes impossible to tell what’s real and what’s illusion.

- Visual Impact: Welles uses the mirrors to fracture the characters' images, which serves as a metaphor for their fractured personalities and moral ambiguity. The reflections make it difficult for the characters to distinguish friend from foe, much like the moral confusion of the plot itself.

- Symbolism: The mirrors represent the many faces the characters present to the world. Elsa, in particular, is shown in multiple reflections, reinforcing her role as a deceptive femme fatale, hiding her true self beneath layers of manipulation.

- Cinematic Innovation: The shattered glass and reflections also showcase Welles’ visual experimentation, using multiple perspectives and distorted images to create a surreal, nightmarish atmosphere. The sound design—sharp, echoing gunshots and shattering glass—adds to the tension and chaos of the scene.

The Aquarium Scene

The aquarium scene is another visually striking moment that exemplifies Welles’ mastery of visual symbolism and atmosphere. In this scene, Michael meets Elsa at an aquarium, where they stand before a giant tank of fish. The camera captures them in profile, framed by the slow, predatory movements of sharks and other sea creatures.

- Atmosphere: The eerie, underwater lighting and the unsettling presence of the sharks foreshadow the danger and deception that surrounds Elsa. It adds a sense of doom to their conversation, as if both characters are already trapped, unable to escape the deadly games being played.

- Symbolism: The sharks in the tank mirror the predatory nature of the characters. Elsa, who at first seems innocent and vulnerable, is revealed as more dangerous and manipulative, much like the sharks circling in the tank.

- Visual Composition: Welles plays with the characters’ reflections in the glass, further emphasizing the film’s theme of identity and illusion. The cool, underwater lighting gives the scene a dreamlike quality, reinforcing the film’s noir atmosphere.

Grisby’s Proposition

In this strange and offbeat scene, George Grisby (Glenn Anders) proposes a bizarre plan to Michael O’Hara, asking him to "kill" him in a fake murder plot. Grisby’s eccentric behavior and unsettling dialogue make this scene stand out as one of the film’s more surreal moments.

- Tone and Dialogue: The dialogue is deliberately disjointed and absurd, with Grisby speaking in a manic, almost nonsensical tone. His casual talk of murder contrasts with the real danger that underpins the scene. This creates a sense of unease and foreshadows the chaos to come.

- Performance: Glenn Anders' performance as Grisby is one of the film’s most memorable, as he plays the character with a strange mix of humor and menace. His jittery, off-kilter energy makes this scene a key turning point in the film, as it sets the plot in motion.

- Psychological Depth: The proposition marks the beginning of Michael’s deeper entanglement in the web of crime and deception. Grisby’s offer seems outlandish at first, but it pulls Michael into a deadly game, blurring the lines between reality and illusion.

The Courtroom Scene

The courtroom sequence is both surreal and darkly comedic, showcasing Welles’ talent for blending genres. Arthur Bannister (Everett Sloane), a defense attorney by trade, represents Michael in a murder trial, even though he’s also his enemy. This creates an unusual and uncomfortable dynamic.

- Tension and Irony: The idea of Bannister defending Michael, even as he despises him, adds a layer of tension and absurdity to the scene. Bannister uses his legal expertise to manipulate the trial, toying with both the law and Michael’s fate.

- Dark Comedy: Welles infuses the courtroom scene with humor, as Bannister’s cruel wit and sharp legal mind dominate the proceedings. The trial feels like a game, with Michael as a pawn, reflecting the corrupt, morally ambiguous world of the film.

- Psychological Discomfort: The scene highlights the power dynamics at play, with Bannister exerting control over Michael’s life. The trial itself becomes a metaphor for the larger manipulation and betrayal that pervades the film.

Michael and Elsa’s First Meeting

Michael O'Hara's first encounter with Elsa Bannister in Central Park sets the tone for their dangerous relationship. Michael rescues Elsa from a group of attackers, immediately casting himself as the knight in shining armor. However, this moment of heroism is layered with foreboding, as Michael narrates his own downfall with a sense of inevitability.

- Foreshadowing: From the very beginning, Welles frames their meeting as the start of something destructive. Michael’s voiceover hints that he knows he’s making a mistake by getting involved with Elsa, but he can’t help himself.

- Chemistry: The chemistry between Hayworth and Welles is palpable in this scene. Hayworth’s Elsa is seductive and mysterious, while Welles’ Michael is captivated by her beauty and vulnerability. Their interaction is charged with tension, signaling the doomed nature of their relationship.

- Visual Style: The use of shadows and fog in the park gives the scene a noir atmosphere, suggesting that the characters are stepping into a world of uncertainty and danger. The setting—dark, foggy, and isolated—mirrors the moral fog that will envelop Michael as he becomes more involved with Elsa.

Awards and Recognition

The Lady from Shanghai (1947) did not receive any major awards or nominations during its initial release. Despite Orson Welles’ reputation and the star power of Rita Hayworth, the film was not a commercial or critical success at the time, largely due to studio interference, editing issues, and its unconventional narrative style, which audiences and critics found confusing.

Retrospective Recognition:

Although The Lady from Shanghai didn’t garner awards in its day, over the years, it has earned a place in the canon of film noir classics. The film is now widely appreciated for its innovative direction, cinematography, and the famous "hall of mirrors" sequence, which is regarded as one of the most iconic scenes in cinema history.

- National Film Registry: In 2018, The Lady from Shanghai was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress. This designation recognizes films that are "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."

Today, the film is studied and appreciated for its contributions to the noir genre and for Orson Welles' artistic vision, even though it wasn’t widely recognized with awards at the time of its release.