The Jazz Singer – 1927

Summary of The Jazz Singer (1927)

The Jazz Singer is a groundbreaking film in cinematic history, celebrated as the first feature-length movie with synchronized dialogue and music sequences, marking the dawn of the "talkies." Directed by Alan Crosland, it tells the poignant story of Jakie Rabinowitz, a young Jewish man torn between family tradition and his dreams of stardom.

The film opens with Jakie, the son of a strict Cantor, singing popular songs in a saloon against his father’s wishes. Cantor Rabinowitz, who upholds the traditions of their Jewish faith, is furious and demands Jakie abandon his passion for secular music to follow in his footsteps as a cantor. Unable to reconcile his love for modern music with his father's expectations, Jakie leaves home, vowing to pursue his dreams.

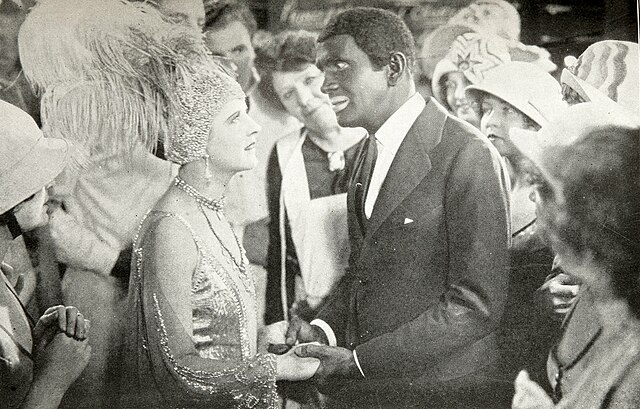

Years later, Jakie reemerges as Jack Robin, a successful jazz singer. He meets Mary Dale, a talented dancer who becomes his romantic partner and helps him secure an audition for a prestigious Broadway show. Jack's career soars, and he is poised to achieve his dream of headlining a major production.

However, a personal conflict disrupts his ambitions. Jack’s father falls ill just as Yom Kippur, the holiest day in Judaism, approaches. The family tradition dictates that Jack, as the son of the cantor, must sing the Kol Nidre prayer in his father’s place. Torn between his career-defining performance and his duty to his family and faith, Jack faces an emotional dilemma.

In the film’s climactic moment, Jack chooses to honor his father and sings the Kol Nidre at the synagogue. The scene is deeply moving, emphasizing the reconciliation of Jack’s dual identities. After fulfilling this duty, Jack returns to his Broadway show, symbolizing his ability to balance his heritage and his dreams.

The film ends with Jack performing for a packed audience, his mother watching proudly, signifying her acceptance of his choices. Though his father has passed, Jack’s journey reflects a poignant resolution between tradition and individuality.

________________________________________

Analysis of The Jazz Singer

Cultural and Historical Significance

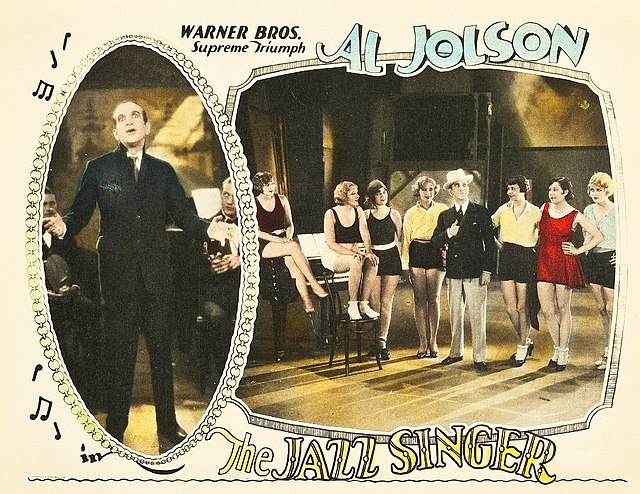

The Jazz Singer is often celebrated not just for its narrative but for its technological achievements. Released in 1927, it marked the transition from silent films to "talkies," forever changing the film industry. The movie's integration of synchronized sound, particularly Al Jolson’s dynamic performances of songs like "Toot, Toot, Tootsie! (Goo' Bye)" and "Blue Skies," captivated audiences and demonstrated the potential of sound in storytelling.

The film also explores themes of cultural assimilation and generational conflict. Jakie's struggle reflects the experiences of many immigrant families in America during the early 20th century, torn between preserving their heritage and embracing new opportunities in a rapidly modernizing society.

Themes

• Tradition vs. Modernity: The central conflict of the film revolves around Jakie’s desire to break free from the confines of tradition and pursue a modern, secular life. His journey is a metaphor for the broader societal shifts of the time, as America embraced industrialization and cultural evolution.

• Family and Identity: The film portrays the universal struggle to reconcile personal ambitions with familial expectations. Jakie’s ultimate decision to honor his father reflects the enduring importance of family bonds, even amidst personal turmoil.

• Cultural Assimilation: The film highlights the challenges faced by immigrants in balancing their cultural identity with the pressures to assimilate into American society. Jakie's transformation into Jack Robin symbolizes his attempt to navigate these dual identities.

Performances and Cinematic Techniques

Al Jolson’s performance is electric, showcasing his charisma and talent as a singer and performer. His line, “You ain’t heard nothin’ yet!” became iconic, capturing the excitement of the film’s innovative use of sound.

The use of synchronized sound was revolutionary for the time, blending silent film techniques with new audio technology. Though much of the film remains silent with title cards, the musical sequences are vibrant and dynamic, providing a glimpse of the future of cinema.

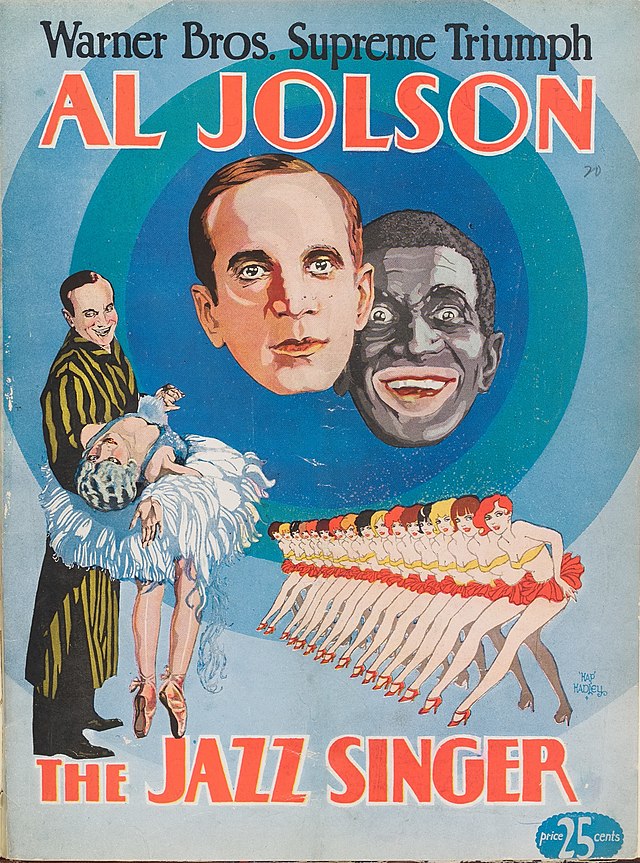

Controversies

While The Jazz Singer is undeniably significant, it is not without criticism. Al Jolson performs in blackface during a key scene, a practice rooted in minstrel traditions. This portrayal is now widely regarded as racist and offensive, detracting from the film’s legacy for modern audiences. It serves as a reminder of the pervasive racial insensitivity in early Hollywood.

Legacy

The Jazz Singer is a landmark in film history, ushering in the era of sound and altering the trajectory of the industry. Its story of personal and cultural reconciliation continues to resonate, though it must be understood within the context of its time, including its problematic elements.

The film is more than a tale of one man’s dreams; it’s a reflection of the American experience during a transformative era. Despite its controversies, The Jazz Singer remains a pivotal work in cinema, remembered for its technical innovation and cultural impact.

Official Trailer The Jazz Singer

Full Cast

• Al Jolson as Jakie Rabinowitz / Jack Robin

• May McAvoy as Mary Dale

• Warner Oland as Cantor Rabinowitz

• Eugenie Besserer as Sara Rabinowitz

• Otto Lederer as Moisha Yudelson

• Robert Gordon as Young Jakie Rabinowitz

• Richard Tucker as Harry Lee

• Yossele Rosenblatt as Himself (Cantor at the Synagogue)

• Jane Chardiet as Miss Morrison

• Anders Randolf as Stage Manager

Analysis of Alan Crosland’s Direction in The Jazz Singer (1927)

Alan Crosland’s direction of The Jazz Singer was instrumental in shaping a film that not only captured the attention of audiences in 1927 but also revolutionized the cinematic landscape. His approach combined traditional silent film techniques with pioneering sound integration, creating a unique storytelling experience that bridged two eras of filmmaking.

Pioneering the Transition to Sound

Crosland’s direction skillfully navigated the challenges of incorporating synchronized sound, a technological innovation at the time. While much of the film remains silent with intertitles, Crosland ensured that the sound segments, particularly Al Jolson’s musical performances, felt seamlessly integrated into the narrative. These moments, such as the iconic “Blue Skies” sequence, are vibrant and engaging, showcasing Crosland’s ability to harness sound as a narrative tool without overwhelming the visual storytelling.

Crosland demonstrated a clear understanding of the power of sound to enhance emotional resonance. For instance:

• The live performance sequences are filmed in a way that highlights Jolson’s charisma, using minimalistic camera movements to let the audio and performance take center stage.

• The Kol Nidre scene, in particular, is deeply moving due to Crosland’s direction, which balances the solemnity of the moment with the emotional weight of Jakie’s choice, amplified by the inclusion of synchronized sound.

Balancing Tradition with Innovation

Crosland’s direction delicately handles the film’s dual identity: as a silent film adhering to conventional cinematic grammar and as an innovative "talkie" exploring new technological possibilities. This balance reflects the film’s central themes of tradition versus modernity. Crosland does not abandon the visual storytelling techniques of the silent era; instead, he integrates them with sound to create a hybrid form that feels both familiar and groundbreaking.

For example:

• In scenes without sound, Crosland uses expressive close-ups, deliberate lighting, and poignant intertitles to convey the characters’ emotions and advance the plot.

• In the sound sequences, the performances are allowed to unfold naturally, with Crosland using long takes and simple staging to emphasize the novelty and intimacy of the synchronized dialogue and music.

Emotional Depth and Cultural Sensitivity

Crosland’s direction succeeds in bringing emotional depth to the story, particularly in its exploration of family and cultural conflict. The tension between Jakie and his father is rendered with a keen sensitivity to their differing perspectives.

Crosland uses visual contrasts to underscore this conflict:

• The synagogue scenes are depicted with reverence and intimacy, using soft lighting and static compositions to emphasize the sacredness of tradition.

• In contrast, Jakie’s performances as Jack Robin are vibrant and dynamic, with Crosland employing brighter lighting and more energetic pacing to reflect his embrace of modernity.

Use of Visual and Cinematic Language

Crosland’s visual storytelling retains the hallmarks of silent cinema while hinting at the future potential of sound films. He makes effective use of:

• Framing and Composition: Crosland often frames Jakie in isolation during moments of internal conflict, visually reinforcing his estrangement from both his family and his new life.

• Lighting and Atmosphere: The film’s lighting is pivotal in creating mood. The synagogue scenes are bathed in warm, low-key lighting that feels timeless, while the stage performances are bright and theatrical, reflecting Jakie’s transformation.

• Pacing: The direction ensures that the transitions between the silent and sound sequences feel natural, maintaining a rhythm that keeps the audience engaged.

Challenges and Limitations

While Crosland’s direction was groundbreaking, it also reflects some of the limitations of the time. The pacing occasionally lags in the silent portions, which may feel dated to modern audiences. Additionally, the inclusion of blackface in Jolson’s performance, while a product of its era, is now recognized as a deeply problematic element that mars the film’s legacy.

Legacy of Crosland’s Direction

Alan Crosland’s work on The Jazz Singer demonstrated his ability to adapt to a rapidly changing industry. His direction helped establish the artistic and commercial viability of sound films, paving the way for future directors to experiment with audio-visual storytelling. Crosland’s efforts were integral to making The Jazz Singer a landmark in cinema history, blending emotional storytelling with technical innovation in a way that resonated with audiences of his time and continues to be studied today.

In summary, Alan Crosland’s direction of The Jazz Singer exemplifies the intersection of tradition and innovation, mirroring the film’s narrative themes. His ability to embrace new technology while honoring the art of silent filmmaking ensured that the movie not only succeeded commercially but also achieved enduring historical significance.

Al Jolson’s Performance in The Jazz Singer (1927)

Al Jolson’s performance in The Jazz Singer is a central reason for the film’s enduring legacy, as his charisma, energy, and emotional range captivated audiences and brought a new level of dynamism to cinematic acting. Jolson’s portrayal of Jakie Rabinowitz (later Jack Robin) is deeply personal, drawing on his own experiences as a performer navigating cultural and generational divides. His performance not only highlighted the dramatic possibilities of synchronized sound but also explored themes of identity and ambition with emotional nuance.

________________________________________

Vocal and Physical Presence

Jolson’s performance is primarily remembered for his groundbreaking use of synchronized sound, particularly in the musical sequences. As a seasoned vaudeville and Broadway performer, Jolson brought an electrifying stage presence to the film, which translated brilliantly to the screen:

• Singing Style: Jolson’s rich, expressive voice and distinctive phrasing brought the film’s musical numbers to life. His performances of songs like “Blue Skies” and “Toot, Toot, Tootsie! (Goo' Bye)” are energetic and infectious, showcasing his ability to connect with an audience through both sound and emotion.

• Body Language: Even in silent portions of the film, Jolson’s exaggerated gestures and facial expressions, honed through years of stage work, conveyed the inner turmoil and aspirations of his character. His physicality complements the restrained performances of the supporting cast, creating a compelling contrast.

________________________________________

Emotional Depth and Characterization

Jolson’s portrayal of Jakie Rabinowitz captures the emotional complexity of a man torn between two worlds—his familial obligations and his personal dreams:

• Inner Conflict: Jolson excels in scenes where Jakie struggles to reconcile his dual identities as the son of a cantor and a jazz singer. The Kol Nidre sequence is particularly powerful, as Jolson conveys Jakie’s deep respect for his father and heritage through subtle expressions and his heartfelt delivery of the prayer.

• Ambition and Joy: Jolson imbues Jack Robin with an infectious enthusiasm for life and music. His joy during the performance scenes is palpable, allowing audiences to understand why Jack feels compelled to follow his dreams, even at great personal cost.

________________________________________

Iconic Moments

Jolson’s delivery of the now-famous line, “You ain’t heard nothin’ yet!” epitomizes his natural charisma and ability to engage the audience. This ad-libbed phrase not only captured the excitement of sound cinema but also demonstrated Jolson’s instinctive understanding of timing and audience connection.

Another standout moment is his performance of “My Mammy,” where Jolson, in blackface, sings with a raw emotional intensity that underscores Jakie’s longing for acceptance. While the blackface performance is rightly criticized today for its racial insensitivity, it reflects the complexities of performance traditions at the time and the cultural tensions embedded in the narrative.

________________________________________

Jolson’s Personal Connection to the Role

Jolson’s own life mirrored Jakie Rabinowitz’s in significant ways. As the son of Jewish immigrants, he likely drew on his personal experiences of balancing tradition with the allure of modern entertainment. This connection lends authenticity to his portrayal, particularly in moments of familial tension and reconciliation.

________________________________________

Limitations and Controversies

While Jolson’s performance is celebrated, it is also not without its limitations and criticisms:

• Stage Actor’s Exaggeration: Jolson’s theatrical acting style, though effective in the musical numbers, sometimes feels overly broad in quieter, dramatic scenes. This can make his performance appear dated to modern audiences accustomed to more subdued film acting.

• Blackface: The use of blackface in Jolson’s performance is a major blemish on both his legacy and the film’s. While it was a common practice in early 20th-century entertainment, it perpetuates harmful racial stereotypes and is now viewed as deeply offensive. This aspect of his performance complicates discussions of his artistry and the film’s cultural impact.

________________________________________

Legacy of Jolson’s Performance

Jolson’s work in The Jazz Singer demonstrated the potential of sound in cinema, not just as a technological novelty but as a way to enhance emotional storytelling. His vibrant energy and heartfelt singing brought new life to the screen, making The Jazz Singer an unforgettable experience for audiences of the time.

Despite the controversies surrounding his performance, Jolson’s contribution to cinema cannot be overlooked. His ability to embody the conflict between tradition and modernity resonated with contemporary viewers and helped establish him as one of the first major stars of the "talkie" era.

In conclusion, Al Jolson’s performance in The Jazz Singer is a study in contrasts—technically innovative yet rooted in outdated cultural practices, exuberantly theatrical yet deeply personal. It is this duality that makes his work both memorable and complex, securing its place in the history of film while inviting ongoing reflection and critique.

Notable Quotes from the Movie

• Jakie Rabinowitz/Jack Robin:

"You ain't heard nothin' yet!"

This iconic line, delivered by Al Jolson during a performance, became emblematic of the film and the transition to synchronized sound in cinema.

• Cantor Rabinowitz (to young Jakie):

"Stop! Your voice was given you by God. You will use it only in His service."

This line highlights the central conflict of the film, with Jakie's father emphasizing the sacredness of their tradition.

• Jakie Rabinowitz/Jack Robin:

"I can’t sing it, Papa. I can’t sing it the way you want."

Spoken during an emotional confrontation, this line underscores Jakie’s internal struggle between his love for secular music and his father's expectations.

• Jakie Rabinowitz/Jack Robin:

"Mother, if Pop knew about this, he’d throw me out—he’d double-quick time me to the door!"

Jakie’s playful yet serious acknowledgment of his father’s disapproval, showing his awareness of the cultural and generational divide.

• Sara Rabinowitz:

"Your papa is very sick. Maybe he will never sing again. Will you sing in his place, Jakie?"

This plea from Jakie’s mother is a pivotal moment, presenting him with the choice to honor his father’s legacy or pursue his own ambitions.

• Jakie Rabinowitz/Jack Robin (during his performance of "My Mammy"):

"I’d walk a million miles for one of your smiles, my Mammy!"

This heartfelt line from the song reflects Jakie’s deep connection to his mother and the emotional pull of his family roots.

• Jakie Rabinowitz/Jack Robin:

"If you can’t be the best, what’s the use of being anything?"

This line expresses Jakie’s ambition and determination to succeed in his chosen path, even at great personal cost.

Classic Scenes from The Jazz Singer (1927)

The Jazz Singer is remembered for several iconic scenes that blend emotional storytelling with innovative filmmaking, marking its place as a cinematic milestone. Here are some of the most significant and classic moments from the film:

________________________________________

"You Ain’t Heard Nothin’ Yet!"

• Scene Description: In one of the most celebrated moments in film history, Jack Robin (Al Jolson) breaks from the silent-film tradition, speaking directly to the audience before launching into a lively rendition of "Toot, Toot, Tootsie! (Goo' Bye)."

• Significance:

o This was the first time many audiences heard synchronized speech in a feature film, and the phrase became emblematic of the transition to sound cinema.

o The scene captures Jolson’s charisma, blending dialogue, music, and performance into an unforgettable cinematic moment.

________________________________________

Jakie Singing "Blue Skies" for His Mother

• Scene Description: Jakie serenades his mother, Sara Rabinowitz (Eugenie Besserer), with the song "Blue Skies." His playful and affectionate performance contrasts with the tension surrounding his relationship with his father.

• Significance:

o The scene highlights Jakie’s deep love for his mother and serves as a poignant reminder of his struggle to balance family and ambition.

o The use of synchronized singing creates an intimate and tender moment, showcasing the emotional potential of sound in film.

________________________________________

The Kol Nidre Scene

• Scene Description: Jakie is called upon to sing the Kol Nidre prayer in place of his ailing father during Yom Kippur. He steps into the synagogue, donning his prayer shawl, and delivers a heartfelt rendition of the sacred chant.

• Significance:

o This is the emotional climax of the film, symbolizing Jakie’s reconciliation with his faith and family.

o The solemnity of the prayer, combined with Jakie’s visible internal conflict, creates a powerful moment of reflection and redemption.

o It emphasizes the film’s central themes of tradition, duty, and identity.

________________________________________

Jakie’s Performance of "My Mammy"

• Scene Description: In the film’s finale, Jakie performs the sentimental ballad "My Mammy" in front of a packed audience, dedicating the song to his mother. The performance is emotional, with Jakie expressing both gratitude and longing.

• Significance:

o This scene encapsulates Jakie’s journey, showing his success as an entertainer while reaffirming his connection to his roots.

o Though marred by the use of blackface, which reflects the problematic racial attitudes of the time, the scene remains a pivotal moment in the narrative and Jolson’s performance.

________________________________________

Jakie Rebelling Against His Father

• Scene Description: As a young boy, Jakie defies his father’s wishes by singing a secular song in a saloon, leading to a heated confrontation. Cantor Rabinowitz declares that his son will never sing anything other than sacred music.

• Significance:

o This early scene establishes the central conflict of the film, setting the stage for Jakie’s departure and his lifelong struggle between familial duty and personal ambition.

o The emotional intensity of the father-son relationship is a recurring motif throughout the story.

________________________________________

Reunion with His Mother

• Scene Description: After years away from home, Jakie reunites with his mother, who welcomes him with open arms despite his estrangement from his father. The scene is filled with warmth and tenderness.

• Significance:

o This moment underscores the unconditional love of a parent and Jakie’s enduring ties to his family, even as he pursues a life they don’t fully understand.

o It serves as a counterbalance to the harsher dynamics with his father.

Awards and Recognition for The Jazz Singer

The Jazz Singer is widely celebrated for its historical significance, though it was released before the modern awards landscape was fully established. Despite this, it received recognition at the inaugural Academy Awards in 1929, where its groundbreaking contributions to film technology and storytelling were honored.

________________________________________

Academy Awards (1st Oscars - 1929)

• Honorary Award:

Awarded to Warner Bros. for producing The Jazz Singer, "the pioneer outstanding talking picture, which has revolutionized the industry."

This was not a competitive award but an acknowledgment of the film's revolutionary impact on the medium.

________________________________________

Legacy Recognition

While it did not compete in traditional categories like Best Picture or Best Director, The Jazz Singer is recognized as a turning point in cinema history. It has received numerous accolades in subsequent years for its influence and innovation:

• National Film Registry:

In 1996, The Jazz Singer was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."

• AFI (American Film Institute):

Ranked #90 on the AFI's 100 Years…100 Movies list (1998) as one of the greatest American films.

Included in the AFI’s list of the most important movie quotes for "You ain’t heard nothin’ yet!" (#71).