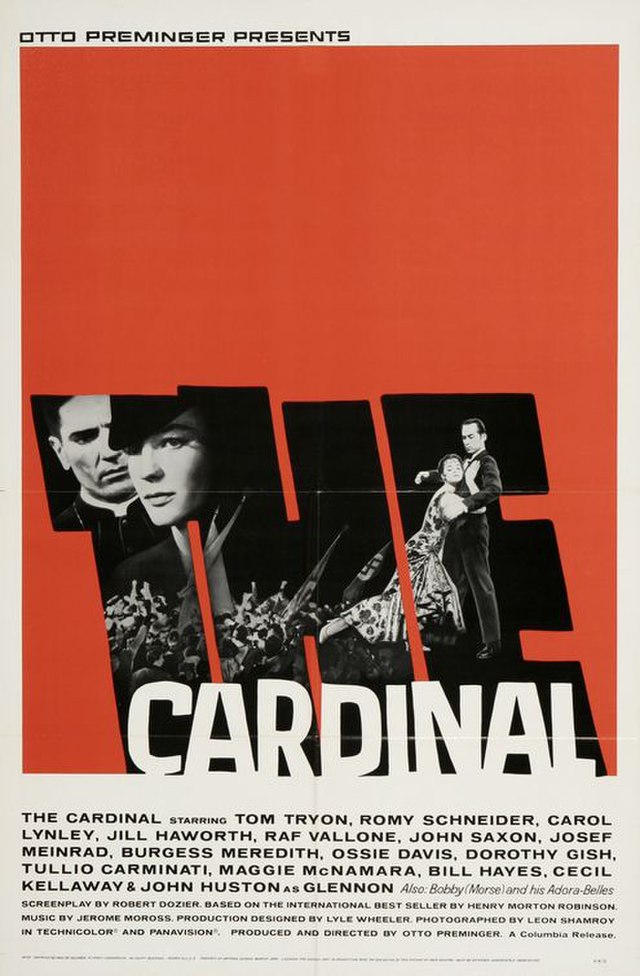

The Cardinal - 1963

back| Released by | Columbia Pictures |

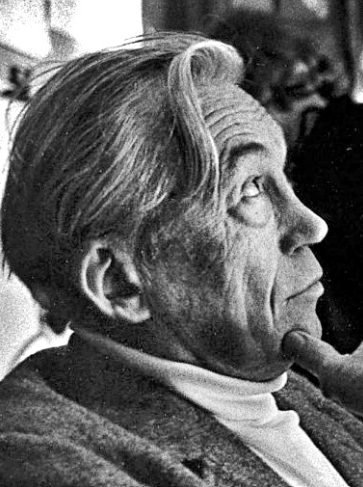

| Director | Otto Preminger |

| Producer | Otto Preminger |

| Script | Robert Dozier (screenplay), based on the novel The Cardinal by Henry Morton Robinson |

| Cinematography | Leon Shamroy |

| Music by | Jerome Moross |

| Running time | 175 minutes |

| Film budget | $4 million |

| Box office sales | $11.1 million |

| Main cast | Tom Tryon - Romy Schneider - Carol Lynley - Dorothy Gish - Maggie McNamara - John Huston |

The Cardinal

A Sweeping Exploration of Faith and Moral Conflict within the Catholic Church

The Cardinal (1963), directed by Otto Preminger, follows the spiritual and moral journey of Stephen Fermoyle (Tom Tryon), a young priest rising through the ranks of the Catholic Church.

The film was praised for its ambitious scope, tackling controversial topics like abortion, racism, and the Church’s political complicity, making it a provocative exploration of faith and power. While The Cardinal had mixed critical reception, it left a lasting impact as a bold depiction of moral struggles within the Catholic Church.

Related

The Cardinal – 1963

Summary of The Cardinal (1963):

The Cardinal, directed by Otto Preminger, is an epic drama set in the early 20th century, based on the novel by Henry Morton Robinson. The film chronicles the life and career of Stephen Fermoyle (played by Tom Tryon), an ambitious young Irish-American priest, as he rises through the ranks of the Catholic Church amidst personal trials, moral dilemmas, and significant historical events.

The story begins with Stephen’s ordination as a priest in Boston. Soon after, he is sent to Austria, where he falls in love with Annemarie von Hartman (Romy Schneider), the daughter of a prominent aristocratic family. Though he is tempted to leave the priesthood for her, Stephen remains committed to his calling, enduring a heart-wrenching internal struggle.

The film then follows Stephen’s journey through various phases of his religious career, each episode presenting a moral and ethical test. One of the key subplots involves his sister, Mona Fermoyle (Carol Lynley), who becomes pregnant out of wedlock. Stephen is faced with a dilemma between family loyalty and his religious convictions, as his stern response leads Mona to reject the Church’s teachings. Tragically, she dies during childbirth, a moment that haunts Stephen and further deepens his internal conflict.

Stephen’s journey also includes time spent in the southern United States, where he confronts issues of racial injustice. This encounter shapes his understanding of the broader human condition and challenges him to reconcile his personal beliefs with the institutional rigidity of the Church.

In a later episode, Stephen is sent to Italy, where he witnesses the rise of fascism. The growing threat of Nazi power brings him into direct conflict with the political forces of the time, placing him at the center of global religious and social turmoil. His moral courage is tested again when he witnesses the dangers of complacency and complicity in the face of fascism.

Throughout the film, Stephen is mentored by various high-ranking clergy, including Cardinal Glennon (John Huston) and Cardinal Quarenghi (Raf Vallone), who see great potential in him. His eventual rise to the rank of cardinal, one of the most powerful positions in the Church, symbolizes the culmination of his spiritual journey. However, his path is not one of easy triumph; it is one of deep personal sacrifice, fraught with the tension between individual desire, family duty, and faith.

The film concludes with Stephen accepting his appointment as a cardinal, having endured numerous trials. The experience has humbled him, and he is now a wiser, more compassionate man, prepared to serve the Church in a role of great responsibility.

Analysis:

The Cardinal is an exploration of personal faith, moral challenges, and the intersection of religion and political power. At its heart, the film is a character study of Stephen Fermoyle, a man of deep conviction whose journey is marked by both triumph and tragedy. Otto Preminger's direction and Robert Dozier’s screenplay give the film an operatic scope, dealing with grand themes like love, duty, and the conflict between personal ambition and religious calling.

One of the central themes of the film is the tension between religious doctrine and the demands of human relationships. Stephen’s love for Annemarie and his failure to save his sister Mona reveal the personal costs of his unwavering dedication to the Church. His internal conflict mirrors the broader conflict between tradition and modernity, as Stephen must navigate a rapidly changing world that challenges the authority of the Catholic Church.

The film is also a political and social commentary, particularly in its treatment of issues such as racial inequality and the rise of fascism. Stephen’s experiences in the American South and in pre-World War II Europe force him to confront the limits of institutional power and the Church’s role in global affairs. These episodes reveal Stephen’s growth as he transitions from a naïve priest to a more worldly and morally complex figure.

Visually, The Cardinal is notable for its grandeur, with Leon Shamroy’s cinematography capturing the epic scope of the narrative. The film makes extensive use of location shooting in Europe, lending an air of authenticity to its historical settings. The Church’s grandeur is juxtaposed with the personal struggles of its clergy, highlighting the often isolating experience of serving an institution that demands so much.

Jerome Moross’s musical score underscores the film’s dramatic intensity, further enhancing the epic feel of the narrative. The score blends moments of spiritual reflection with tension-filled sequences, complementing the film’s thematic complexity.

Themes:

- Faith vs. Personal Desires: Stephen’s journey reflects the constant battle between his religious devotion and his personal feelings, especially seen in his relationships with Annemarie and his sister Mona. The film questions the cost of absolute dedication to one’s vocation.

- Institutional Power and Social Responsibility: The film presents the Catholic Church as a powerful institution but also highlights its involvement in social and political issues. Stephen’s encounter with racism in the American South and the Church’s stance during the rise of fascism reflect the Church’s engagement with pressing social matters.

- Moral Dilemmas and Human Imperfection: Stephen’s path is riddled with moral choices that reveal his imperfections as a human being, despite his religious commitment. His inability to prevent Mona’s tragedy and his struggles with temptation show that even clergy are subject to human failings.

- Political and Historical Context: The rise of fascism and the Church’s reaction to it form a critical backdrop to the film. Stephen’s transformation occurs within this context, and the film implicitly critiques the Church’s complicity in certain political situations, especially in Nazi-occupied Europe.

Cinematic and Historical Importance:

The Cardinal was controversial upon its release due to its frank portrayal of subjects like abortion, racism, and anti-Semitism—topics rarely explored in Hollywood films of the time, especially in a film centered around the Catholic Church. Otto Preminger, known for his bold choices, didn’t shy away from confronting these issues head-on, which gives the film a timeless quality.

While the film may feel melodramatic at points, it is precisely this larger-than-life tone that lends it an epic quality. Preminger uses the medium of film not just to tell a personal story, but to paint a broader picture of the human experience through the lens of one man’s spiritual journey. The film's emphasis on real-world politics and historical events enriches the narrative, making it not just a religious film, but a sweeping historical drama.

Though not without its critics, The Cardinal remains an ambitious exploration of faith, morality, and power, anchored by strong performances and a rich visual style.

Official Trailer from The Cardinal

Full Cast:

· Tom Tryon as Stephen Fermoyle

· Romy Schneider as Annemarie von Hartman

· John Huston as Cardinal Glennon

· Carol Lynley as Mona Fermoyle

· Dorothy Gish as Celia Fermoyle

· Maggie McNamara as Regina Fermoyle

· Raf Vallone as Cardinal Quarenghi

· Burgess Meredith as Father Ned Halley

· Jill Haworth as Lalage Menton

· Tullio Carminati as Monsignor Manoel

· Bill Hayes as Frank Fermoyle

· Robert Morse as Father Francis Devlin

· Patrick O'Neal as Cecil, Duke of Wheatland

· Cecil Kellaway as Father Callahan

· Josef Meinrad as Father Schulte

· Heinz Reincke as Lieutenant Lansky

· Wolfgang Preiss as Colonel von Hartman

· John Saxon as Benny Rampell

· William Bassett as Peter, Young Soldier

· James Hickman as Father Flanagan

· Eva Wagner as Sister Johanna

· Ludwig Donath as Dr. Hochberg

· Werner Peters as Colonel von Rantz

· Michele Wolff as Mrs. Schulte

· Robert Easton as Captain Costelli

Otto Preminger’s Direction:

Otto Preminger’s direction of The Cardinal (1963) showcases his unique and meticulous approach to filmmaking, combining his signature style of sweeping visuals, complex characters, and social commentary. Preminger, known for tackling controversial subjects head-on, takes on the ambitious task of adapting Henry Morton Robinson’s sprawling novel into an epic film that explores faith, power, and the human condition.

Visual Grandeur and Cinematic Scale:

Preminger’s direction emphasizes grandeur, both in the physical scope of the film and the weighty themes it tackles. His use of wide shots and extensive location shooting gives the film a distinctly epic quality, placing the characters within grand churches, historical settings, and dramatic landscapes. These vast settings are often contrasted with intimate close-ups that capture the internal struggles of the main character, Stephen Fermoyle (Tom Tryon), as he navigates his spiritual journey. Preminger’s sweeping visual style underscores the sense that the story is not just about one man, but about the larger forces of history, religion, and politics.

The decision to shoot on location, particularly in Rome, Vienna, and Boston, adds authenticity to the historical and ecclesiastical backdrop of the story. Preminger’s ability to create a sense of place immerses the audience in the world of the early 20th century, lending an air of historical accuracy that heightens the dramatic stakes of the narrative.

Attention to Detail and Narrative Complexity:

Preminger’s direction reflects a deep understanding of the complexities within the Catholic Church and the political landscape of the time. He meticulously portrays the rituals, hierarchy, and internal politics of the Church, presenting them with a respectful yet unflinching lens. The film avoids romanticizing the Church and instead shows it as an institution grappling with its own contradictions, particularly when it comes to issues like racism, anti-Semitism, and political complicity during the rise of fascism.

One of Preminger’s strengths as a director is his ability to weave multiple narrative threads together without losing the audience. The Cardinal spans several decades and covers a variety of historical and personal events, yet Preminger ensures that each subplot—whether it be Stephen’s personal conflicts or the Church’s political challenges—feeds into the larger narrative. This kind of narrative complexity is a hallmark of Preminger’s films, where characters often face moral dilemmas that resist easy resolution.

Handling Controversial Themes:

Preminger was no stranger to tackling controversial themes, and The Cardinal is no exception. The film addresses issues such as racial injustice, fascism, abortion, and anti-Semitism, all within the framework of the Catholic Church’s influence. Preminger’s direction balances these weighty topics with a sense of moral ambiguity, never offering clear-cut answers but instead presenting the complexity of these social issues.

For example, in the scenes set in the American South, where Stephen confronts racial inequality, Preminger avoids heavy-handed moralizing. Instead, he allows the situation to unfold naturally, showing how Stephen’s experiences shape his understanding of justice. This approach reflects Preminger’s belief that film should provoke thought rather than dictate solutions.

The portrayal of the Church’s interactions with fascism in Italy is similarly handled with nuance. Preminger doesn’t shy away from showing the Church’s fraught relationship with political power, depicting a spectrum of responses from the clergy—some complicit, others actively resisting. This layered approach to storytelling is emblematic of Preminger’s directorial style, where institutional critique is presented without undermining the humanity of the characters involved.

Character-Driven Direction:

At the heart of The Cardinal is Stephen Fermoyle’s spiritual and moral journey, and Preminger’s direction ensures that the film’s epic scope never overshadows the character’s personal story. Through Stephen, Preminger explores themes of ambition, guilt, duty, and sacrifice, presenting a protagonist who is deeply flawed but also capable of growth. Preminger’s handling of Stephen’s inner conflict—particularly his struggles with family loyalty, personal desire, and his devotion to the Church—imbues the film with emotional depth.

Preminger’s direction draws strong performances from his actors, particularly Tom Tryon, whose reserved and stoic portrayal of Stephen Fermoyle captures the character’s internal conflict. Preminger’s use of close-ups on Tryon’s face, often during moments of decision or reflection, emphasizes the weight of the choices Stephen faces, inviting the audience to empathize with his struggles.

Similarly, Romy Schneider’s portrayal of Annemarie von Hartman, the woman with whom Stephen almost falls in love, is handled with sensitivity and restraint. Preminger’s direction ensures that this subplot never becomes melodramatic, instead framing it as a reflection of the personal sacrifices that come with spiritual dedication.

Thematic Depth and Moral Ambiguity:

One of Preminger’s defining characteristics as a director is his refusal to offer simple moral resolutions, and this is evident in The Cardinal. Throughout the film, Stephen is faced with dilemmas where no choice is entirely right or wrong, whether it’s his response to his sister Mona’s pregnancy or his involvement in global political affairs. Preminger’s direction emphasizes the grey areas of these decisions, reflecting his belief that life—and faith—are inherently complex and filled with contradictions.

This moral ambiguity extends to the portrayal of the Church itself. While the Church is depicted as a powerful force for good, it is also shown to be flawed, especially in its handling of political and social issues. Preminger’s nuanced direction allows the audience to see the Church as both a spiritual refuge and a bureaucratic institution, without resorting to simplistic critiques or blind reverence.

Control and Precision:

Preminger was known for his tight control over every aspect of his films, from the performances to the editing. This precision is evident in The Cardinal, where every scene is carefully composed to serve the larger narrative. The film’s pacing, though deliberate, reflects the gradual unfolding of Stephen’s character arc and the broader historical events surrounding him. Preminger’s control over the film’s tone, especially in balancing personal drama with epic historical events, ensures that the film maintains its cohesion despite its sprawling scope.

Otto Preminger’s direction of The Cardinal is a masterclass in balancing narrative complexity, thematic depth, and visual grandeur. His ability to weave together personal and institutional conflicts, while addressing controversial social issues, results in a film that is both intellectually provocative and emotionally resonant. Preminger’s insistence on moral ambiguity, coupled with his meticulous attention to detail, makes The Cardinal not just a historical drama, but a thoughtful exploration of faith, power, and the human experience.

The film reflects Preminger’s broader philosophy as a director: cinema should challenge its audience, presenting the world in all its complexity and encouraging reflection on the most profound questions of life, faith, and morality.

Tom Tryon’s Performance in The Cardinal:

Tom Tryon’s performance as Stephen Fermoyle in The Cardinal (1963) is central to the film’s success, as his portrayal anchors the sweeping narrative and reflects the deep moral and emotional journey of the character. Tryon, who was relatively lesser-known at the time compared to some of his co-stars, delivers a restrained, introspective performance that effectively captures Stephen’s inner turmoil and transformation over the course of the film.

Character Depth and Internal Struggle:

Stephen Fermoyle’s journey is one of profound internal conflict, and Tryon’s portrayal embodies this struggle through subtle shifts in his demeanor and emotional expression. From the outset, Stephen is a man torn between his personal desires and his religious vocation. Tryon’s performance avoids melodrama, relying instead on quiet, contemplative moments to show Stephen’s moral wrestling. His reserved nature serves the character well, as Stephen is often reflective and introspective, contemplating the difficult decisions he must make in his rise through the ranks of the Church.

In scenes where Stephen faces personal crises—such as his attraction to Annemarie von Hartman (Romy Schneider) or the tragedy surrounding his sister Mona (Carol Lynley)—Tryon’s performance communicates the weight of these moments not through overt displays of emotion, but through controlled, internalized acting. His measured reactions give the impression of a man who is deeply troubled but remains composed, as if constantly battling to maintain his sense of duty over his personal feelings.

Portrayal of Ambition and Growth:

Tryon effectively captures Stephen’s ambition and the sense of purpose that drives him throughout the film. In the early parts of the movie, Stephen is portrayed as somewhat idealistic, eager to serve the Church and prove himself within its hierarchy. Tryon conveys this youthful ambition with a mix of confidence and naivety, allowing the audience to see Stephen as a man with high aspirations, yet unaware of the profound personal and moral costs his path will demand.

As Stephen’s journey unfolds and he experiences the complexities of his role in the Church, including his encounters with political power, racial injustice, and global conflict, Tryon subtly shifts his portrayal. The early idealism gives way to a more weary and reflective demeanor, as Stephen begins to comprehend the enormity of his responsibilities and the imperfections within the institution he serves. Tryon’s ability to show this gradual transformation is a testament to his skill, as he manages to balance the character’s inherent sense of duty with a growing disillusionment and self-awareness.

Emotional Restraint:

One of the defining characteristics of Tryon’s performance is his emotional restraint. While the film deals with highly charged subjects—family tragedy, political upheaval, and spiritual conflict—Tryon never allows Stephen to become overly dramatic. Instead, he often conveys emotion through body language and subtle facial expressions, giving the character an air of dignity and control that is fitting for a man of the cloth. This restrained approach makes Stephen’s few moments of emotional release all the more powerful.

For example, in the scenes dealing with Mona’s pregnancy and subsequent death, Tryon’s restrained performance communicates Stephen’s deep guilt and sorrow. Rather than resorting to overt displays of grief, Tryon’s stillness and internalized pain speak volumes, making his performance feel more authentic and moving. This emotional subtlety is key to understanding Stephen as a character—someone who is deeply conflicted but must maintain a composed exterior as he navigates the demands of his position within the Church.

Navigating Moral Complexity:

Stephen Fermoyle is a character constantly faced with moral dilemmas, and Tryon’s performance reflects the nuances of these conflicts. Whether confronting his own personal desires, navigating the Church’s stance on social issues, or witnessing the rise of fascism in Europe, Tryon imbues Stephen with a sense of inner conflict that feels real and relatable. His portrayal captures the essence of a man trying to do the right thing, even when the right course of action is unclear or painful.

Tryon’s ability to project this moral complexity is particularly evident in scenes where Stephen must confront institutional authority. When Stephen challenges the Church’s stance on certain political matters, or when he grapples with his own failures, Tryon subtly conveys the frustration and doubt that come with being part of a rigid institution. His performance allows the audience to see Stephen not just as a religious figure, but as a human being grappling with his own limitations and those of the Church.

Chemistry with Co-Stars:

Tom Tryon’s interactions with his co-stars further enhance his portrayal of Stephen Fermoyle. His chemistry with Romy Schneider, who plays Annemarie von Hartman, brings depth to the romantic tension between their characters. Tryon’s restrained performance mirrors Stephen’s internal struggle between his religious vows and his attraction to Annemarie. Their scenes together are filled with unspoken emotions, and Tryon’s subtle approach helps convey the intensity of the situation without overt romanticism, making the conflict all the more poignant.

Similarly, Tryon’s interactions with John Huston’s Cardinal Glennon and Raf Vallone’s Cardinal Quarenghi highlight Stephen’s evolving relationship with authority figures within the Church. Tryon plays off these veteran actors with a sense of deference and respect, while also revealing Stephen’s growing confidence and independence as he matures. These dynamics add richness to Stephen’s character arc, showing him transitioning from a young priest seeking approval to a man capable of making his own difficult decisions.

A Quiet Presence Amidst an Epic Scope:

In a film as large in scope as The Cardinal, it would be easy for an actor to get lost amidst the historical and political backdrop. However, Tom Tryon’s quiet, steady performance grounds the film, ensuring that the emotional and spiritual journey of Stephen Fermoyle remains the focus. His performance acts as a calm center around which the film’s grand events unfold, lending the character a gravitas that fits his eventual rise to the rank of cardinal.

Tryon’s understated presence also allows the film’s larger themes—faith, power, duty—to resonate more deeply. Rather than being overwhelmed by the film’s epic scale, Tryon’s performance provides a sense of introspection, ensuring that the audience remains connected to Stephen’s personal journey even as the film addresses significant historical and social issues.

Criticism and Legacy:

While Tom Tryon’s performance received mixed reviews upon the film’s release, with some critics finding his portrayal too subdued or lacking charisma, his approach has since been appreciated for its subtlety and thoughtfulness. Tryon’s portrayal of Stephen Fermoyle is one of emotional restraint, befitting the character of a man of faith who must wrestle with his own human desires and failings. His performance might not have been flashy, but it was effective in conveying the complexity of a character who is constantly balancing personal conviction with institutional duty.

In retrospect, Tryon’s nuanced performance fits well within the larger context of the film, providing a thoughtful, introspective lens through which to explore The Cardinal’s themes of faith, morality, and sacrifice. His quiet strength and internalized emotional struggles are reflective of a man deeply committed to his faith, yet constantly aware of the weight of his decisions, making his portrayal both compelling and deeply human.

Notable Film Lines:

· Cardinal Glennon (John Huston) to Stephen Fermoyle:

"We don’t make the choice, Stephen. The choice is made for us. All we can do is decide how to live with the decision."

This quote reflects the idea that life, especially within the religious calling, often brings situations where choices are dictated by circumstances or faith, and the challenge lies in accepting and navigating them.

· Stephen Fermoyle (Tom Tryon):

"I feel like a man who can’t quite reach his dream, but keeps trying in spite of it."

Stephen expresses his inner conflict and the sense of striving toward an ideal that constantly eludes him, a key theme in his personal and spiritual journey.

· Father Ned Halley (Burgess Meredith):

"The Church isn’t a building, Stephen. It’s people. And people aren’t perfect."

This quote emphasizes the film’s exploration of the Church as an institution composed of flawed individuals, highlighting the tension between religious ideals and human imperfection.

· Cardinal Quarenghi (Raf Vallone):

"Sometimes to do nothing is the hardest job of all."

This line speaks to the moral and spiritual struggles within the Church, where inaction or restraint can be more difficult than taking action, especially in times of political and social upheaval.

· Cardinal Glennon:

"In the end, we must all face ourselves, Stephen. That is the hardest judgment of all."

A powerful reflection on self-judgment, this quote encapsulates the film’s theme of personal responsibility and the internal reckoning each character faces throughout the story.

· Stephen Fermoyle:

"The hardest thing is not choosing between good and evil, but between two goods."

This quote reveals one of the central moral dilemmas in the film, where Stephen is often faced with choices that are not clear-cut, representing the complexity of his journey as a man of faith.

· Father Francis Devlin (Robert Morse):

"Faith is a mystery, and sometimes the greater the mystery, the stronger the faith."

This line speaks to the idea that faith, by its very nature, is about belief in the unknown and the unknowable, which is a theme that runs throughout Stephen’s spiritual and personal trials.

· Regina Fermoyle (Maggie McNamara):

"You think because you wear a collar, you’re above all human feelings?"

This quote challenges Stephen’s struggle with balancing his human emotions and relationships with his role in the Church, highlighting the personal sacrifices he must make.

Classic Scenes from the Movie:

The Cardinal (1963) contains several memorable and classic scenes that define both its dramatic arc and thematic depth. These scenes not only highlight the moral and personal challenges faced by the characters but also reflect the grandeur of Otto Preminger’s direction. Below are some key scenes that stand out in the film:

Stephen's Ordination

This early scene sets the tone for the entire film, showcasing Stephen Fermoyle's (Tom Tryon) deep commitment to his faith. The grandeur of the Catholic Church is on full display, with the ceremonial richness of his ordination framed by sweeping camera movements and a majestic score. The solemnity of the event is palpable, emphasizing the weight of Stephen’s spiritual responsibility and foreshadowing the personal struggles he will face in maintaining his vows.

Stephen’s Temptation and Romance with Annemarie von Hartman

One of the central emotional conflicts of the film is Stephen’s near-romantic relationship with Annemarie von Hartman (Romy Schneider). In a critical scene set in Austria, Stephen is torn between his religious calling and his attraction to Annemarie. The scene is understated, with Otto Preminger relying on subtle gestures and lingering looks to convey the tension. As the two share a quiet, intimate moment, Stephen’s internal struggle is clear—he is deeply drawn to Annemarie, but his commitment to the Church prevents him from acting on his feelings. This scene is pivotal in showcasing the personal sacrifices Stephen must endure in his path toward priesthood.

Mona’s Pregnancy and Death

Perhaps the most emotionally charged scene in the film is when Stephen’s sister Mona (Carol Lynley) becomes pregnant out of wedlock, and Stephen’s response leads to tragic consequences. The confrontation between Stephen and Mona, where she pleads for his understanding, is intense and heart-wrenching. Stephen’s adherence to Church doctrine drives him to condemn her actions, but his inability to reconcile family loyalty with his religious beliefs results in devastating guilt when Mona dies in childbirth.

This scene marks a turning point for Stephen, as it forces him to confront the consequences of rigidly adhering to doctrine without considering compassion. The subsequent sequence of Mona’s death is particularly impactful, filled with quiet sorrow, and Tryon’s restrained performance captures the deep remorse and regret that will haunt Stephen for the rest of the film.

Stephen Confronts Racism in the American South

One of the more socially relevant scenes is when Stephen is sent to the American South, where he witnesses racial segregation and injustice. In a particularly powerful sequence, Stephen tries to intervene in a lynching, only to be met with hostility from the local authorities. The scene is significant not only for its portrayal of racial tensions but also for Stephen’s growing awareness of the Church’s moral responsibilities beyond religious dogma. The brutality and injustice Stephen witnesses deeply affect him, forcing him to broaden his understanding of his role as a priest and as a man of conscience in a divided society.

The Rise of Fascism in Italy

As Stephen’s journey takes him to Italy, he becomes a witness to the rise of fascism. One of the film’s most politically charged scenes occurs when Stephen observes a Nazi rally and realizes the Church’s uneasy relationship with the fascist regime. The scene is chilling, with the camera capturing the fervor of the rally and the oppressive power of the Nazi presence. This sequence represents another key moment in Stephen’s personal evolution, as he grapples with the Church’s role in resisting or accommodating political tyranny.

The visual contrast between the grandiosity of the Church and the stark brutality of fascism serves as a powerful metaphor for the moral challenges faced by Stephen and the Catholic Church during this period. The film uses this scene to explore the complicity and courage of religious institutions in times of political crisis.

Stephen’s Final Ascension as a Cardinal

The closing scene of the film, where Stephen is appointed as a cardinal, is the culmination of his spiritual and moral journey. This scene is not just about achievement but about the weight of responsibility that Stephen must now carry. Otto Preminger directs this sequence with grandeur, using the visual splendor of the Vatican to convey the significance of the moment. Stephen’s quiet acceptance of his new role, juxtaposed against the majestic visuals, reflects his transformation into a man who has been shaped by both personal tragedy and the broader social and political events of the time.

In this final scene, there is a sense of both triumph and humility in Stephen’s character. The film concludes on a reflective note, with Stephen now fully aware of the cost of his ascension within the Church—both the personal sacrifices he has made and the moral obligations he must fulfill in his new role.

Stephen’s Confession

One of the most intimate and revealing scenes is when Stephen enters the confessional, opening up about his guilt and sense of failure, particularly regarding his sister Mona’s death. This scene is a powerful depiction of vulnerability and the internal conflict between religious duty and human emotion. Tryon’s performance shines in this moment of introspection, and the dialogue brings out Stephen’s struggle with the immense burden of his decisions. The dim lighting and close framing create a somber, reflective atmosphere, emphasizing the gravity of the confessional act and Stephen’s need for redemption.

Stephen’s Meeting with Cardinal Quarenghi

In another classic scene, Stephen meets with Cardinal Quarenghi (Raf Vallone), who becomes both a mentor and a figure of authority for him. This pivotal conversation delves into the complexities of faith, obedience, and the real-world responsibilities of the clergy. Quarenghi’s pragmatic wisdom offers Stephen a broader perspective on his role in the Church, helping to shape his understanding of leadership. The dialogue between the two characters is both philosophical and practical, making this scene a reflection on the Church’s balancing act between spiritual ideals and political realities.

Awards and Recognition for The Cardinal

Academy Awards (Oscars) – 1964

Nominations:

- Best Director – Otto Preminger

- Best Supporting Actor – John Huston

- Best Film Editing – Louis R. Loeffler

- Best Cinematography (Color) – Leon Shamroy

- Best Art Direction (Color) – Lyle R. Wheeler, Gene Callahan, Boris Leven, William H. Tuntke, Edward G. Boyle

Golden Globe Awards – 1964

Wins:

- Best Motion Picture – Drama

- Best Supporting Actor – John Huston

- Best Director – Otto Preminger

Nominations:

- Best Actor in a Motion Picture – Drama – Tom Tryon

BAFTA Awards – 1964

Nominations:

- Best Foreign Actor – Tom Tryon

Laurel Awards – 1964

Nominations:

- Top Drama

- Top Male Dramatic Performance – Tom Tryon (4th place)

- Top Supporting Performance – Male – John Huston (3rd place)

Directors Guild of America (DGA) Awards – 1964

Nominations:

- Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Motion Pictures – Otto Preminger

National Board of Review (NBR) – 1963

Wins:

- Top Ten Films of 1963

- Best Supporting Actor – John Huston