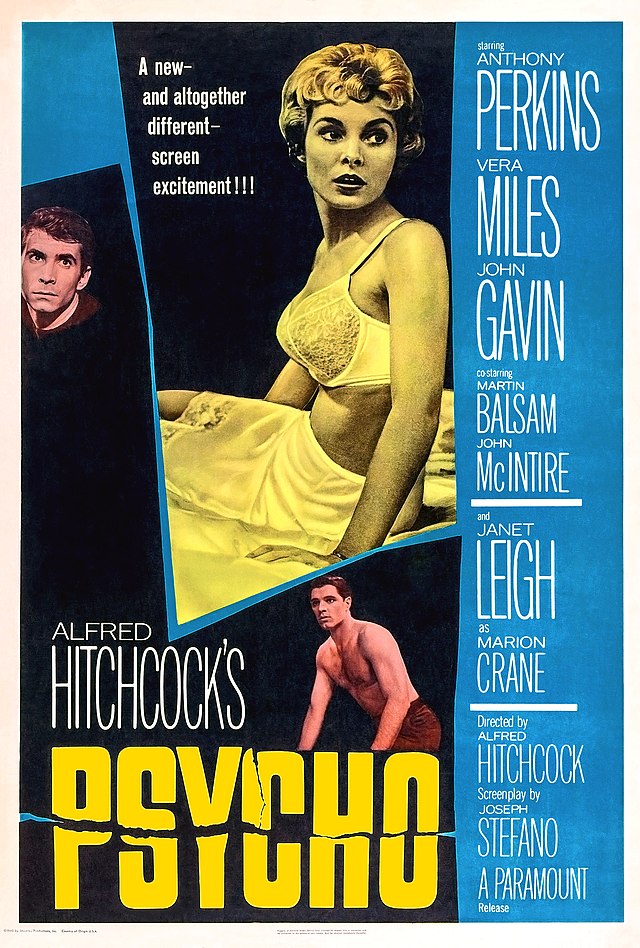

Psycho - 1960

back| Released by | Paramount Pictures |

| Director | Alfred Hitchcock |

| Producer | Alfred Hitchcock |

| Script | Joseph Stefano (based on the novel Psycho by Robert Bloch) |

| Cinematography | John L. Russell |

| Music by | Bernard Herrmann |

| Running time | 109 minutes |

| Film budget | $806,947 |

| Box office sales | $50 million |

| Main cast | Anthony Perkins - Janet Leigh - Vera Miles - John Gavin - Martin Balsam |

Psycho

The Ultimate Psychological Horror Movie

Psycho's impact on cinema is profound. It redefined the thriller and horror genres, with Hitchcock's subversion of narrative expectations and innovative use of suspense, editing, and music (notably Bernard Herrmann's score).

The shocking narrative twists and psychological depth set new standards for storytelling. Psycho also pushed boundaries in its depiction of violence and sexuality, becoming a cultural touchstone and influencing countless filmmakers and the slasher genre.

Related

Psycho – 1960

Summary

Psycho begins with Marion Crane (played by Janet Leigh), a secretary in Phoenix, Arizona, who steals $40,000 from her employer's client. Marion, wanting to help her boyfriend Sam Loomis (John Gavin) pay off his debts so they can finally marry, decides to run away with the money. She leaves town and drives for several hours, eventually stopping at the secluded Bates Motel, which is run by the nervous yet charming Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins).

Norman lives in a large, gothic-style house behind the motel with his domineering mother, who he speaks about often in strange terms. Marion and Norman engage in a conversation where Norman reveals the strained, suffocating relationship with his mother. Afterward, Marion decides to return the stolen money and make things right, but this decision is tragically cut short.

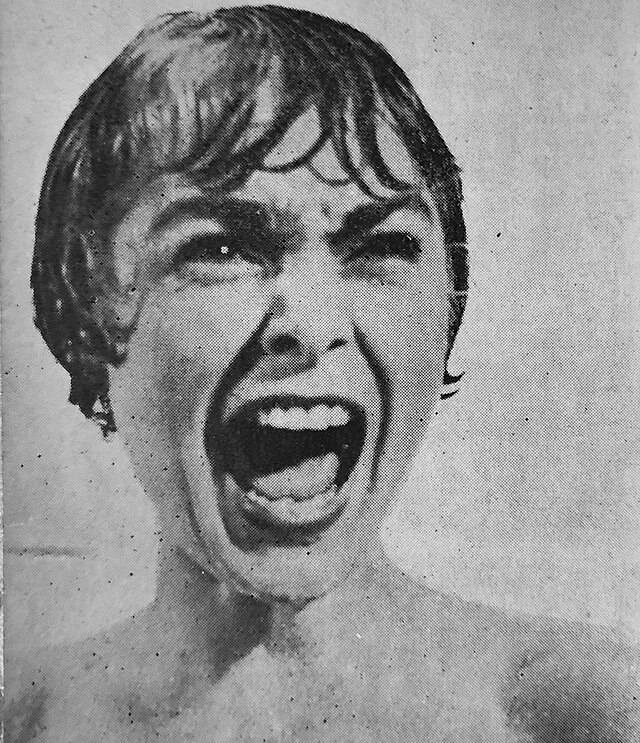

In one of the most iconic scenes in cinema history, Marion is brutally murdered in the shower by what appears to be an older woman. The scene is shocking for both its violence and its surprise, as Marion was assumed to be the protagonist of the film.

The second half of the movie shifts focus to Marion’s sister, Lila Crane (Vera Miles), and Sam, who begin searching for her when she fails to return home. A private detective named Arbogast (Martin Balsam) is also on her trail and eventually finds the Bates Motel. After asking too many questions, Arbogast meets a similar fate as Marion.

Lila and Sam eventually discover the terrifying truth: Norman Bates is not just the meek motel owner he appears to be. Norman has been assuming the identity of his deceased mother, dressing in her clothes and speaking in her voice. It is revealed that "Mother" had died years earlier in a murder-suicide that Norman had staged. His guilt over the event fractured his psyche, creating a split personality. Norman’s “Mother” personality had taken over and was responsible for the murders of Marion and Arbogast.

The film ends with Norman being apprehended, though the final scene reveals that the "Mother" personality has completely taken over his mind, with Norman’s own personality seemingly extinguished.

Analysis

Themes

- Duality and Split Personality: The most prominent theme in Psycho is the idea of duality, represented by Norman’s split personality. Norman Bates appears as a polite, somewhat awkward young man, but he harbors a darker personality—the persona of his dead mother. The division within Norman mirrors the dual nature of the human psyche, where the conscious self hides darker, repressed desires. The film explores the theme of identity and how it can be fragmented under intense psychological pressure.

- Voyeurism and Privacy: Hitchcock frequently explores voyeurism in Psycho. From the opening scene where the camera follows Marion in her hotel room, to Norman’s spying on Marion through a peephole, the film makes the audience feel complicit in invading the privacy of its characters. This theme forces the audience to question their role as viewers—are we merely passive observers, or is there something more sinister about our need to watch?

- Maternal Influence and Repression: Norman's relationship with his mother is one of the most significant elements in the film. His mother dominates him even after her death, reflecting Hitchcock’s ongoing exploration of complex maternal figures in his films. Norman’s inability to break free from her influence leads to a repression of his own desires and emotions, which ultimately explode into violence.

- Guilt and Responsibility: Both Marion and Norman struggle with guilt, albeit for different reasons. Marion’s guilt stems from stealing the money, and we see her inner turmoil during the drive to the Bates Motel. Norman’s guilt is far deeper, rooted in his traumatic past and the murders he commits while under the influence of his "Mother" persona. The film raises questions about personal responsibility, especially in Norman’s case, where his fractured mind obscures his own culpability.

Cinematic Techniques

- Shower Scene: The shower scene is one of the most famous moments in cinema, both for its shock value and its technical brilliance. Hitchcock used rapid editing (with 78 camera setups for a 45-second sequence) to create the illusion of violence without ever actually showing the knife penetrating Marion's body. The jarring cuts, combined with Bernard Herrmann’s shrieking string score, create a sense of terror that feels both real and surreal. This scene is also remarkable for subverting narrative expectations by killing off the apparent protagonist early in the film, leaving the audience unsettled.

- Music: Bernard Herrmann’s score plays an essential role in Psycho, heightening the tension and terror of key moments. The piercing violin theme during the shower scene is perhaps the most famous musical moment in horror cinema, accentuating the shock and violence of the murder. The music itself feels like an extension of Norman’s fractured psyche, growing more dissonant and frenzied as the film progresses.

- Lighting and Shadows: Hitchcock uses lighting masterfully to convey Norman’s inner turmoil and to add layers of tension. The Bates house, often shown in silhouette against a stormy sky, looms like a gothic castle over the desolate motel. Inside, the use of shadows helps to obscure and distort reality, particularly in scenes where Norman is in his "Mother" persona. This visual style gives the film a distinctly eerie, noir-like atmosphere.

- The Use of Mirrors: Throughout Psycho, mirrors are used as a motif to reflect characters' internal struggles. They symbolize duality and self-reflection, particularly in Norman’s case, where the mirror becomes a literal representation of his fractured self. Marion, too, is often framed by mirrors, reflecting her own inner conflict about the money she has stolen.

Psycho’s Impact on Cinema

Psycho was groundbreaking not only for its shocking plot twist and innovative techniques but also for its influence on the horror and thriller genres. It essentially gave birth to the "slasher" subgenre, inspiring countless films that followed in its footsteps, from Halloween to Friday the 13th. It was also significant in pushing the boundaries of what was acceptable in mainstream cinema, particularly in its depiction of violence, sexuality, and mental illness.

Hitchcock’s meticulous direction, the shocking plot, and Anthony Perkins' chilling portrayal of Norman Bates left an indelible mark on cinema, creating one of the most iconic villains in film history. Perkis' sympathetic yet terrifying performance ensured that Norman Bates would remain a complex and memorable character, making the audience both repulsed and intrigued by his psychological plight.

Psycho is more than just a horror film; it is a study of the human psyche, repressed desires, and the fragility of identity. Its innovative use of narrative structure, music, and visual storytelling set it apart as a true masterpiece of cinema. Hitchcock’s exploration of dark themes, such as the duality of human nature and the destructive power of repression, continues to resonate with audiences, ensuring Psycho’s legacy as one of the greatest films of all time.

Classic Trailer Psycho 1960

Full Cast

· Anthony Perkins as Norman Bates

· Janet Leigh as Marion Crane

· Vera Miles as Lila Crane

· John Gavin as Sam Loomis

· Martin Balsam as Detective Milton Arbogast

· John McIntire as Sheriff Al Chambers

· Simon Oakland as Dr. Fred Richman (the psychiatrist)

· Frank Albertson as Tom Cassidy (the client whose money Marion steals)

· Patricia Hitchcock as Caroline (Marion's co-worker)

· Vaughn Taylor as George Lowery (Marion's employer)

· Lurene Tuttle as Mrs. Chambers

· Mort Mills as the Highway Patrol Officer

· John Anderson as California Charlie (the used car salesman)

· Alfred Hitchcock (cameo) as the man standing outside Marion's office with a cowboy hat

Analysis of Alfred Hitchcock’s Direction

Alfred Hitchcock’s direction in Psycho (1960) is often regarded as a masterclass in suspense, psychological tension, and innovative filmmaking. His approach to Psycho was calculated and daring, combining technical precision with storytelling finesse to create a film that not only terrified audiences but also pushed the boundaries of what was considered acceptable in mainstream cinema at the time. Here's a descriptive analysis of his direction:

Mastery of Suspense:

Hitchcock, known as the "Master of Suspense," crafted Psycho with the explicit goal of keeping the audience on edge from start to finish. He carefully manipulates tension throughout the film, drawing viewers into a world where the unexpected seems inevitable. Instead of relying on jump scares or overtly supernatural elements, Hitchcock builds suspense through anticipation, visual cues, and the underlying dread of what might happen next.

One of Hitchcock’s most famous principles was his use of "the bomb theory" of suspense: letting the audience know something dangerous is present but delaying the moment it explodes. In Psycho, this technique is embodied in moments like the famous shower scene—where the tension builds gradually before the sudden and shocking murder of Marion. The audience is lulled into a false sense of security, only to be jolted by the brutal, swift violence that disrupts the narrative.

Subversion of Expectations:

Hitchcock's direction in Psycho is particularly remarkable for the way he plays with and subverts audience expectations. By casting Janet Leigh, a major star at the time, as the apparent protagonist Marion Crane, Hitchcock gives the audience the impression that the film will follow her journey. However, by killing Marion halfway through the movie in the infamous shower scene, he flips the conventional structure of the thriller on its head. This narrative shock not only left audiences stunned but also made them unsure of what could happen next, enhancing the film’s overall tension.

Hitchcock deliberately misleads the audience to keep them off balance. The first part of the film feels like a crime thriller, focusing on Marion's theft and escape, but it suddenly morphs into a psychological horror story. This shift is a testament to Hitchcock's ability to control the narrative flow, pulling viewers into different emotional states before abruptly changing course.

Psychological Depth and the "Hitchcock Touch":

Hitchcock was fascinated by the darker sides of the human psyche, and Psycho is a perfect vehicle for his exploration of mental illness, repression, and guilt. His direction taps into deep psychological fears, particularly through the character of Norman Bates. Hitchcock takes a deeply psychological approach to storytelling, turning Psycho into more than just a thriller—it becomes an investigation into the fragility of identity and the destructive power of hidden trauma.

Norman Bates, played with chilling complexity by Anthony Perkins, is a quintessential Hitchcock character. Hitchcock's direction guides the audience's empathy and fear in equal measure. Norman, outwardly shy and awkward, becomes increasingly sinister as the layers of his personality are peeled back. Hitchcock’s ability to make Norman both sympathetic and terrifying is a testament to his understanding of the human condition, and it’s what makes the character one of the most enduring in cinematic history.

Visual Storytelling:

Hitchcock was a visual storyteller above all else, often preferring to let images speak louder than dialogue. In Psycho, his camera work and use of framing are crucial to the film’s impact. One of his signature techniques is the use of subjective point-of-view shots, which places the audience directly in the character’s shoes. For example, the scene where Norman spies on Marion through the peephole creates a sense of voyeurism that implicates the viewer, making them feel complicit in his actions.

Another striking visual motif in Psycho is the use of mirrors and reflections, symbolizing the fractured identities of the characters. Hitchcock uses this imagery to hint at the duality within Norman Bates—both as a man and as the embodiment of his mother’s personality. The visual interplay between light and shadow also emphasizes this duality, with the Bates house often bathed in darkness, casting eerie shadows that reflect the psychological turmoil within.

Hitchcock’s meticulous attention to detail is evident in the film’s iconic sets. The Bates Motel and the looming Victorian house above it are not just locations but extensions of Norman’s twisted psyche. The isolation of the motel reflects Norman's own loneliness and his entrapment by his "mother." The house itself becomes almost a character, its dark and foreboding presence hanging over the events of the film, adding to the atmosphere of dread.

Innovative Use of Editing and Sound:

One of the most famous aspects of Hitchcock’s direction in Psycho is his use of editing, particularly in the infamous shower scene. Hitchcock's editing here is revolutionary—he created a scene of intense violence without ever showing the knife actually penetrating the body. The rapid cuts, combined with the jarring music, create an illusion of brutal force that is far more horrifying than any explicit violence. This scene is a triumph of montage, with 78 camera setups for just 45 seconds of footage. The meticulous editing is what gives the scene its legendary impact, turning it into one of the most dissected moments in film history.

Sound also plays a pivotal role in Hitchcock’s direction, and in Psycho, it becomes an essential part of the suspense. Bernard Herrmann’s screeching string score for the shower scene is now iconic, amplifying the horror and panic of the moment. Hitchcock initially planned to have no music during the shower scene, but Herrmann insisted, and the result became one of the most recognizable pieces of film music ever. Hitchcock knew when to let silence or ambient sound take over as well. For example, the eerie quietness of the Bates Motel emphasizes the unsettling isolation and adds to the tension as Marion checks in.

Pushing the Boundaries:

Hitchcock took significant risks with Psycho, both artistically and commercially. He made the film on a low budget, using his television crew from Alfred Hitchcock Presents, and in black-and-white to save costs and to reduce the graphicness of the violence. But even with these constraints, he managed to create a film that looked and felt entirely cinematic. Hitchcock also defied the era’s censorship norms by showing more explicit violence and sexual undertones than was typical in Hollywood films of the time. From Marion’s semi-nude scene to the stark depiction of murder, Hitchcock pushed the limits of what could be shown in a mainstream film, ushering in a new era for thrillers and horror movies.

He was also one of the first directors to create a "no late admission" policy, insisting that audiences be seated before the film started to fully experience the shocking twists. This decision emphasized Hitchcock’s control over how his film was to be seen and experienced, further cementing his status as an auteur with a unique vision.

Manipulation of Audience Expectations:

Perhaps one of Hitchcock’s greatest strengths as a director is his ability to manipulate the emotions and expectations of the audience. Throughout Psycho, he deliberately deceives the viewer, creating misdirection through the narrative and visual cues. The initial focus on Marion Crane and her theft leads the audience to believe that her story will be central to the film. However, her abrupt and violent death throws the narrative off course, leaving viewers disoriented and unsure of what will happen next. Hitchcock effectively "trains" the audience to follow certain expectations, only to shatter them unexpectedly, creating a sense of unease that persists throughout the film.

Conclusion:

Alfred Hitchcock’s direction in Psycho is a tour de force of cinematic craftsmanship. His ability to generate suspense, subvert expectations, and delve into the psychological depths of his characters helped shape the modern thriller and horror genres. Through innovative visual techniques, expert use of sound and editing, and a deep understanding of human fears, Hitchcock created a film that transcends its genre, remaining one of the most influential and studied films of all time. His direction turns Psycho into more than just a story of murder—it becomes a haunting exploration of identity, guilt, and the darker side of human nature.

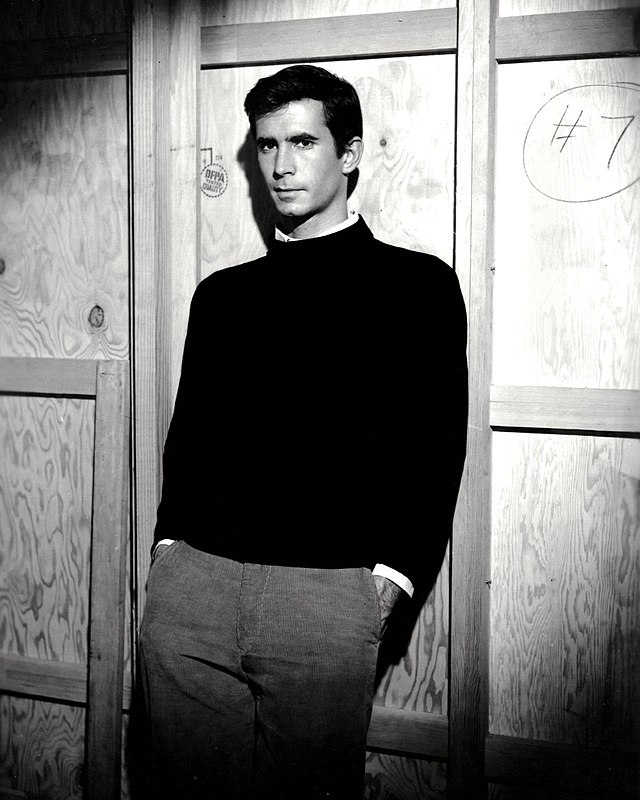

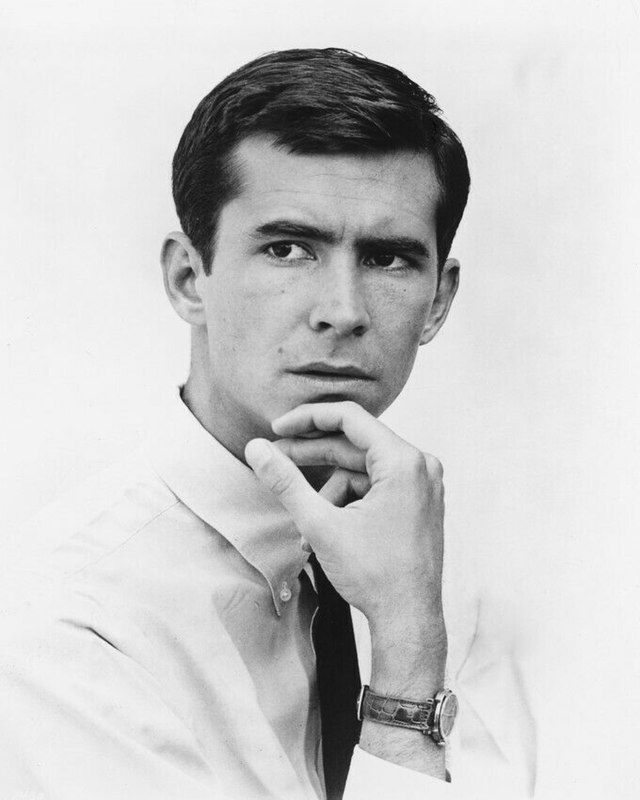

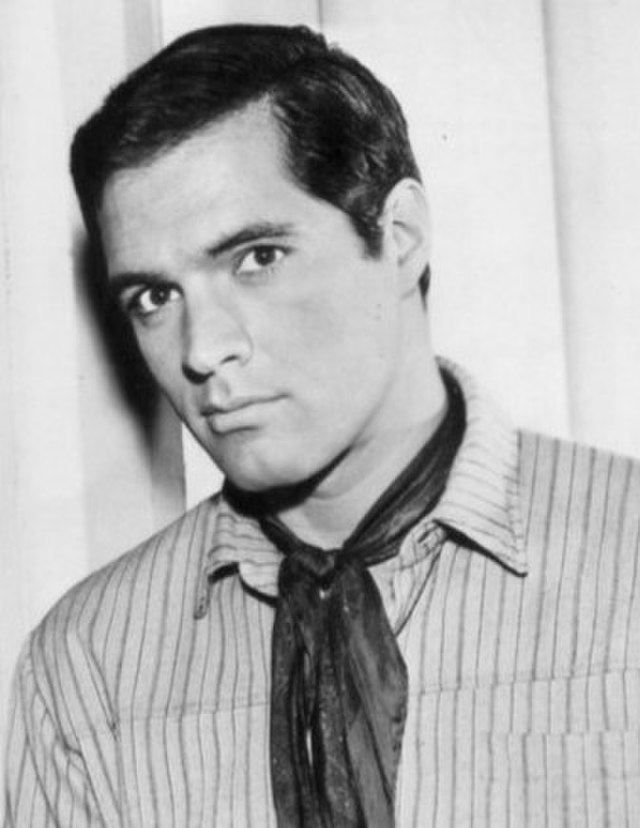

Groundbreaking Performance of Anthony Perkins

Anthony Perkins’ performance as Norman Bates in Psycho (1960) is nothing short of iconic. His portrayal of the disturbed, split-personality motel owner became a defining role in his career and left an indelible mark on cinema. Perkins masterfully navigates the complexity of the character, bringing a unique blend of vulnerability, innocence, and menace to the screen. His nuanced and layered performance remains one of the most memorable aspects of Psycho, and here’s a descriptive analysis of his work:

Layered Vulnerability:

Perkins’ depiction of Norman Bates is remarkable for how he initially presents the character as shy, awkward, and emotionally fragile. His Norman is not the typical antagonist we might expect in a thriller or horror movie. He comes across as socially awkward, almost childlike, with an earnest charm that lulls both the audience and the other characters into a false sense of security. Perkins imbues Norman with a sensitivity that evokes sympathy, making him appear more like a victim of his circumstances than a traditional villain.

In his early scenes with Janet Leigh’s Marion Crane, Perkins plays Norman as someone who is trapped, both literally and figuratively. There is a quiet nervousness in his interactions with her, from the way he stammers through small talk to his fidgety body language. His performance conveys a sense of emotional repression, as if Norman is constantly on edge, trying to maintain control of his carefully hidden inner turmoil. Perkins skillfully balances Norman’s desire for human connection with his deep-rooted psychological trauma, making him a deeply sympathetic and relatable figure despite the sinister undertones of his character.

Psychological Complexity:

One of the most remarkable aspects of Perkins’ performance is how he gradually reveals Norman’s fractured psyche. Throughout the film, he oscillates between two personas: the mild-mannered Norman and the domineering presence of his "mother." What makes Perkins' portrayal so captivating is how he suggests that Norman is, at times, unaware of his own madness. His performance hints at the deep internal conflict Norman faces, as he is both terrified of and dependent on the mother figure that controls him.

Perkins’ ability to portray this psychological duality is one of the key reasons why Psycho works so well. He doesn’t rely on overt transformations to show the shifts between Norman’s personalities; instead, it’s subtle, often conveyed through a change in his posture, facial expressions, or tone of voice. When he speaks about his mother, there is a distinct unease in his mannerisms, as if he is afraid of what she represents, yet utterly beholden to her. Perkins captures the tension between Norman’s innocent persona and the darker forces lurking beneath the surface, making the eventual revelation of his split personality even more horrifying.

The "Boyish Charm" and Innocence:

Perkins' youthful appearance and slender build played a crucial role in shaping the character of Norman Bates. He didn’t fit the mold of the typical movie villain, which added to the character’s unpredictability. His boyish charm gives Norman a facade of innocence, which makes the moments of horror that follow all the more shocking. When we first meet Norman, he appears unthreatening, even pitiable—a young man trapped under the thumb of his overbearing mother, living a lonely existence running the Bates Motel. This charm is disarming, and Perkins uses it to mask the character’s more disturbing traits, allowing Norman to come across as endearing, if slightly eccentric.

There’s a particular scene where Norman talks to Marion about his relationship with his mother while they sit in his parlor filled with stuffed birds. Perkins’ delivery of the line, “We all go a little mad sometimes,” is both unsettling and strangely sympathetic. He delivers it with a quiet, almost apologetic tone, suggesting that Norman is not only explaining his own situation but also acknowledging a universal truth about human nature. Perkins' performance makes Norman’s madness seem like a tragic inevitability rather than an outright evil.

The Subtlety of Threat:

Perkins’ genius lies in how he communicates threat without overt aggression. Norman Bates is not physically intimidating, nor does he exhibit typical traits of a violent person in the beginning. Instead, Perkins uses Norman’s quiet demeanor and odd behaviors to create an underlying sense of danger. There’s a particular tension in the way he interacts with Marion, especially in the scene where he spies on her through a peephole. Perkins conveys a sense of internal conflict—Norman’s fascination with Marion is tinged with a deep, almost subconscious, sense of guilt and shame.

One of the most chilling aspects of his performance is how he switches from vulnerability to threat without warning. In scenes where he defends his mother, Perkins suddenly stiffens and adopts a more forceful tone, as though Norman’s entire identity depends on maintaining the illusion of his mother’s control. It’s in these moments that the cracks in Norman’s fragile psyche begin to show. Perkins never overplays these shifts; they are subtle but enough to make the audience feel a sense of unease. He allows the darkness in Norman to simmer just below the surface, making it all the more terrifying when it finally emerges in full force.

Transformation and the "Mother" Persona:

One of the most challenging aspects of Perkins’ performance is his portrayal of Norman’s transition into the "Mother" persona. Although the mother is never physically seen until the film’s climax, Perkins’ ability to suggest her presence through body language, voice, and psychological transformation is astonishing. In the final moments of the film, when Norman is fully overtaken by the "Mother" personality, Perkins' entire demeanor changes. His posture becomes more rigid, his movements more deliberate, and his facial expressions take on a sinister, almost grotesque quality. His eerie smile in the final scene, as the "Mother" persona fully takes over, is haunting. It’s a moment of pure psychological horror, made all the more effective by the subtlety with which Perkins had hinted at this transformation throughout the film.

Even in earlier scenes, Perkins uses subtle vocal shifts to suggest when the "Mother" persona is asserting itself. When Norman speaks about his mother, his voice trembles with a mix of fear, resentment, and reverence. He makes it clear that Norman’s identity is so enmeshed with his mother’s that it’s difficult to tell where one ends and the other begins. In the moments where "Mother" takes control, Perkins doesn’t rely on exaggerated mannerisms, but rather small, telling changes in his facial expressions or tone. This restraint makes the eventual full revelation of Norman’s split personality all the more impactful.

Tragic Undertones:

What sets Anthony Perkins' portrayal of Norman Bates apart from more one-dimensional villains is the sense of tragedy that he brings to the role. While Norman commits horrific acts, Perkins ensures that he remains a deeply sympathetic character. There is a pervasive sadness to Norman that Perkins conveys, especially in his quieter moments. His Norman is a man who is trapped in a prison of his own making, unable to break free from the mental and emotional chains that his "Mother" has placed on him.

Perkins’ performance suggests that Norman is both victim and perpetrator. This duality is what makes him such a compelling figure. He is a product of abuse, deeply affected by his mother’s control over him, and this dynamic becomes the source of his mental breakdown. Perkins plays Norman as a man who is deeply lonely, longing for human connection but incapable of achieving it due to his fractured mind. This underlying sadness in his portrayal adds a layer of depth to the character, making Norman a tragic figure who evokes as much pity as fear.

Legacy and Impact:

Perkins' performance as Norman Bates has become one of the most iconic in film history. His ability to make the character both terrifying and sympathetic set a new standard for villains in cinema. Norman Bates is not a stereotypical monster; he is a fully realized, deeply flawed human being whose mental illness makes him capable of terrible things. This complexity is what makes Perkins’ portrayal so compelling and enduring.

In conclusion, Anthony Perkins’ performance in Psycho is a masterclass in psychological depth, subtle menace, and emotional complexity. He transforms Norman Bates into a character who is far more than a mere villain—he is a tragic, broken man whose fragility and madness intertwine in a way that keeps audiences both captivated and horrified. Through his nuanced and layered portrayal, Perkins created a character that still resonates in popular culture, making Norman Bates one of the most unforgettable figures in the history of film.

Notable Quotes from Psycho

· "We all go a little mad sometimes." — Norman Bates

This is perhaps the most famous line from the film. Norman says this to Marion Crane in their conversation over dinner, and it captures the essence of Norman’s character and the film’s exploration of madness and psychological duality.

· "A boy's best friend is his mother." — Norman Bates

Norman delivers this line while talking to Marion about his relationship with his mother. It's an eerie foreshadowing of his split personality and his unhealthy, obsessive attachment to his mother.

· "She just goes a little mad sometimes. We all go a little mad sometimes. Haven’t you?" — Norman Bates

This line further illustrates Norman’s dissociative state and introduces the idea that madness is a part of human nature, something that everyone experiences to some degree.

· "I think I must have one of those faces you can’t help believing." — Norman Bates

Norman says this to Marion after she checks into the motel. This line is unsettling because Norman, while appearing harmless, hides a far more dangerous side. It plays into the theme of deception and duality.

· "They're probably watching me. Well, let them. Let them see what kind of a person I am. I'm not even going to swat that fly. I hope they are watching. They'll see. They'll see, and they'll know, and they'll say, 'Why, she wouldn't even harm a fly.'" — Norman Bates (as "Mother")

This chilling final line of the film is delivered after Norman has been fully taken over by the "Mother" personality. It highlights how completely Norman’s identity has been consumed by his alternate persona, adding to the disturbing conclusion.

· "It’s not like my mother is a maniac or a raving thing. She just goes a little mad sometimes!" — Norman Bates

This line subtly hints at Norman’s fractured psyche and his split between his own identity and his "Mother" persona. It downplays the severity of the situation, making the truth even more shocking.

· "Death should always be painless." — Norman Bates

A chilling line that gives insight into Norman’s disturbed mind. It’s unsettling because it shows Norman’s attempt to rationalize and normalize the concept of death.

· "Mother! Oh God, mother! Blood! Blood!" — Norman Bates (as "Mother")

This line occurs after the infamous shower scene when Norman, in his "Mother" persona, realizes what "she" has done. It’s a moment of terror and confusion, further emphasizing Norman’s fragmented identity.

Awards and Recognition

Academy Awards (1961) – Nominations:

- Best Director – Alfred Hitchcock

- Best Supporting Actress – Janet Leigh

- Best Cinematography (Black-and-White) – John L. Russell

- Best Art Direction-Set Decoration (Black-and-White) – Joseph Hurley, Robert Clatworthy, and George Milo

Despite being a critically acclaimed film, Psycho did not win any Oscars.

Golden Globe Awards (1961) – Win:

- Best Supporting Actress – Janet Leigh

Janet Leigh's performance in Psycho earned her the Golden Globe for Best Supporting Actress, marking one of the few major wins for the film at the time.

Directors Guild of America (DGA) Awards (1961) – Nomination:

- Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Motion Pictures – Alfred Hitchcock

National Board of Review (1960) – Win:

- Top Ten Films

Edgar Allan Poe Awards (1961) – Win:

- Best Motion Picture Screenplay – Joseph Stefano

The Edgar Allan Poe Awards, honoring the best in mystery writing, recognized Psycho's screenplay as a standout for its suspenseful and innovative narrative.

Laurel Awards (1961) – Nominations:

- Top Director – Alfred Hitchcock (2nd place)

- Top Supporting Performance, Female – Janet Leigh (2nd place)

- Top Drama (3rd place)

Grammy Awards (1961) – Nomination:

- Best Soundtrack Album or Recording of Music Score from Motion Picture or Television – Bernard Herrmann

Though Psycho is known for its iconic score, Bernard Herrmann was only nominated for a Grammy for his work.

BAFTA Awards (1961) – Nomination:

- Best Foreign Actress – Janet Leigh

Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Films (1974) – Saturn Award (Retrospective Recognition):

- Best DVD Classic Film Release (for home video re-release of Psycho)

Legacy Honors:

Psycho has also been honored in various retrospective rankings and awards, including:

- National Film Registry (1992) – Selected by the U.S. Library of Congress for preservation as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."

- AFI 100 Years... 100 Movies (1998 & 2007) – Ranked #18 on the 1998 list of the greatest American films and #14 in the 2007 update.

- AFI 100 Years... 100 Thrills – Ranked #1 on the list of the greatest American thrillers.

- AFI 100 Years... 100 Heroes & Villains – Norman Bates was ranked #2 on the list of greatest villains in American film history.

Notable Scenes from Psycho

The Shower Scene

- Description: The most famous scene in Psycho is undoubtedly the shower scene where Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) is brutally murdered by an unseen figure. It occurs about halfway through the film, after Marion has checked into the Bates Motel. As she takes a shower, the silhouette of what appears to be an older woman suddenly appears, pulls back the shower curtain, and stabs Marion repeatedly. The quick cuts and Bernard Herrmann’s screeching violin score make the scene terrifying and visceral, even though very little actual violence is shown onscreen.

- Significance: This scene is legendary for its impact on audiences and its innovative use of editing and sound. Hitchcock shot the scene with 78 camera setups and edited it into a 45-second montage, creating the illusion of graphic violence without showing the knife actually penetrating Marion’s body. The rapid cuts disorient the viewer, amplifying the horror of the attack.

Narrative Subversion: Hitchcock kills off what appears to be the film’s main protagonist early in the story, a shocking narrative twist. This subversion of expectations unsettles the audience, leaving them unsure of what might happen next.

Cinematic Legacy: The shower scene has been referenced, imitated, and parodied in countless films and television shows. It’s a masterclass in building suspense and terror through suggestion rather than explicit imagery, showcasing Hitchcock’s genius in manipulating the viewer’s imagination.

The Parlor Scene (Norman and Marion’s Conversation)

- Description: This scene takes place after Marion arrives at the Bates Motel and Norman invites her to the parlor for dinner. They sit surrounded by taxidermied birds as they have a seemingly innocent conversation about life, Marion’s troubles, and Norman’s relationship with his mother. Norman reveals some unsettling details about his mother, including how she is mentally ill and how difficult it is to break free from her control.

- Psychological Insight (continued):

In the parlor scene, when Marion suggests that Norman's mother might be better off in a mental institution, Norman's demeanor subtly shifts from awkward politeness to a quiet but unsettling defensiveness. He responds with the line, "She just goes a little mad sometimes. We all go a little mad sometimes," revealing his own fragile mental state. This scene hints at the split personality within Norman without overtly explaining it, adding to the psychological depth of the character.

Visual Symbolism: The setting of this scene is crucial. The stuffed birds in the parlor are more than just background decorations—they symbolize Norman's own arrested development. Just as the birds are lifeless and frozen in time, Norman too is trapped in a state of psychological stasis, dominated by the memory of his mother. The birds also foreshadow the predatory nature of Norman's "Mother" persona, adding an eerie layer to what seems like a benign conversation.

Tension and Foreshadowing: The scene expertly builds tension without any overt action. Marion is unaware of the danger she is in, but the audience becomes increasingly uncomfortable as Norman's calm exterior cracks. This conversation is a turning point in the film, setting up the shocking events that will follow, including Marion's eventual murder.

The Arbogast Murder Scene

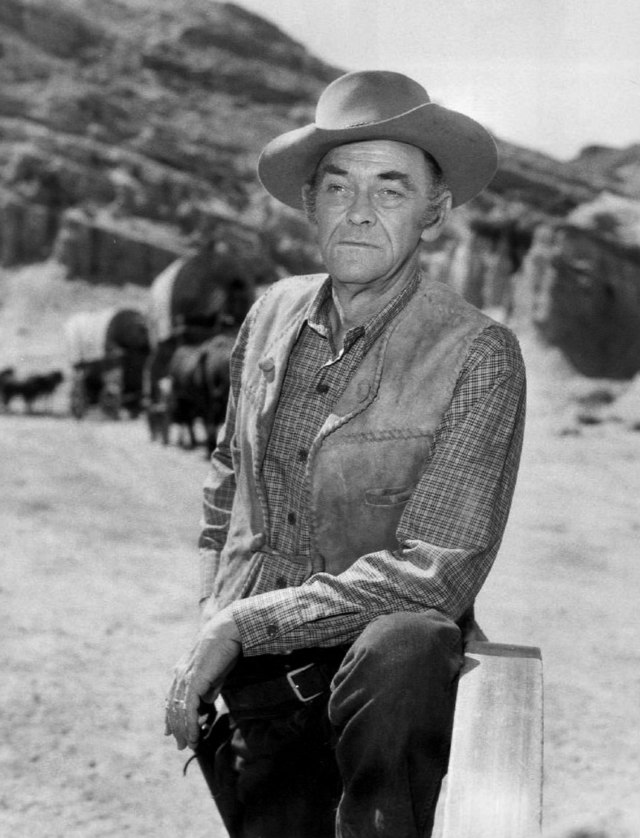

- Description: After private investigator Arbogast (Martin Balsam) follows Marion’s trail to the Bates Motel, he questions Norman and becomes suspicious. Later, Arbogast sneaks into the Bates house to investigate further. As he climbs the stairs inside, the camera shifts to an overhead shot, and suddenly, a figure resembling Norman’s mother emerges from a room and stabs him. The scene is shot in such a way that the viewer sees Arbogast's surprised reaction, followed by a slow, disorienting fall down the stairs as blood runs down his face.

- Significance: Innovative Camera Work: Hitchcock’s decision to use an overhead angle to film the attack is a brilliant way to heighten the tension. The unexpected viewpoint makes the murder more shocking, as it distances the audience from the immediate action but still keeps them in the moment. The slow-motion fall down the stairs, which was achieved using a moving camera shot, adds a surreal quality to the scene, making it stand out as one of the film’s most visually inventive moments.

Misdirection: Just like the shower scene, this moment toys with the audience’s expectations. Arbogast is an experienced detective, and viewers might expect him to uncover the truth. However, Hitchcock subverts this assumption by killing Arbogast in an abrupt and brutal manner, heightening the sense that no one is safe in this story.

Reinforcing Norman’s Duality: The murder of Arbogast continues to build on the theme of Norman’s split personality. While we don’t see the “Mother” figure clearly, the audience increasingly suspects that something is deeply wrong with Norman’s explanation of his mother’s condition. This scene amplifies the mystery surrounding Norman’s identity and builds toward the eventual revelation of his fractured psyche.

The Swivel Chair Reveal (The Truth About "Mother")

- Description: In the film’s climax, Lila Crane (Vera Miles) sneaks into the Bates house to find out the truth about Norman's mother. She makes her way into the basement and finds an old woman sitting in a chair with her back to the door. When Lila touches the figure and spins the chair around, she is horrified to discover a desiccated corpse—Norman’s mother has been dead for years. At that moment, Norman bursts into the room dressed as his mother, brandishing a knife.

- Significance: Iconic Reveal: This is one of the most shocking moments in the film. Hitchcock builds suspense throughout the movie, allowing the audience to question the nature of Norman’s relationship with his mother. The reveal that she has been dead all along is a masterstroke of storytelling, and it serves as the ultimate payoff for the film’s gradual buildup of tension.

Psychological Horror: The reveal also confirms what the audience has been suspecting: Norman Bates has been acting as both himself and his mother. The film transitions from being a traditional thriller into something far more disturbing—a deep dive into mental illness and identity fragmentation. The sight of Norman, dressed as his mother, fully embodies the horror of his psychological breakdown.

Sound and Visuals: Hitchcock uses silence and sudden, jarring action to emphasize the horror of the moment. The swiveling of the chair, the sudden close-up of the mummified corpse, and Norman’s entrance in "Mother's" dress, complete with a wig, create a final crescendo of terror. Bernard Herrmann’s score also plays a crucial role, amplifying the shock and intensity of the scene.

The Final Scene (Norman in the Cell)

- Description: The final scene shows Norman sitting in a police station holding cell, fully consumed by the "Mother" personality. He sits quietly, smiling eerily to himself. As the camera zooms in on his face, the voice of "Mother" is heard in a voiceover, rationalizing that it was Norman, not her, who committed the murders. The last shot superimposes a skull over Norman’s face, hinting that the "Mother" personality has fully taken over.

- Significance: Psychological Resolution: This scene serves as the psychological resolution to the story. Norman’s psyche has been completely overtaken by the "Mother" persona, and the final lines of dialogue delivered in her voice (“Why, she wouldn’t even harm a fly”) add a chilling irony to the situation. Norman has lost his identity entirely, and the audience is left with a lingering sense of dread and tragedy.

Hitchcock’s Use of Visual Symbolism: The superimposed skull on Norman’s face is a subtle but effective visual touch. It reinforces the idea that Norman’s original personality has been "killed" by his mother’s presence in his mind. It also serves as a grim reminder of the death and decay that permeates Norman’s life—both literal (with his mother’s corpse) and metaphorical.

Ambiguity and Horror: The final image of Norman’s serene, yet unnerving smile leaves the audience with a sense of unease. Hitchcock masterfully ends the film on an ambiguous note, allowing the audience to interpret whether Norman is aware of his crimes or if he has truly become the passive victim of his alternate personality.