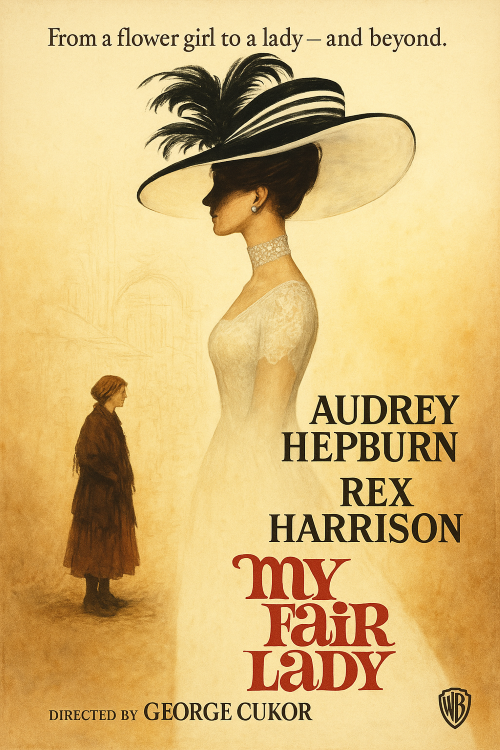

My Fair Lady – 1964

Summary:

Set in Edwardian London, My Fair Lady tells the story of Eliza Doolittle, a poor Cockney flower girl with a thick accent that marks her social class. After a chance encounter at Covent Garden with the self-assured phonetics professor Henry Higgins, Eliza’s life changes dramatically. Higgins boasts to Colonel Hugh Pickering, a fellow linguist, that he could transform any woman — even a common street vendor like Eliza — into a refined lady simply by teaching her to speak properly.

Intrigued, Eliza seeks out Higgins to take speech lessons, hoping to improve her job prospects. Higgins, seeing an opportunity to prove his boast, accepts her as a project, with Pickering wagering that Higgins will succeed in passing Eliza off as a duchess at the Embassy Ball within six months. Thus begins a grueling transformation, during which Eliza endures endless vocal drills and strict discipline.

Meanwhile, Eliza's estranged father, Alfred P. Doolittle, a cheerful dustman with questionable morals, sees an opportunity for personal gain. After selling his daughter’s “rights” to Higgins for a pittance, he unwittingly catapults himself into unwanted "middle-class morality" when he comes into money through a strange twist of fate.

As Eliza’s speech and manners improve, she becomes unrecognizable. She successfully dazzles high society at the Ascot races and ultimately triumphs at the Embassy Ball, where aristocrats, including a foreign linguistics expert, believe she is a royal in disguise.

However, Eliza feels used and unappreciated by Higgins, who credits himself entirely for her success and fails to acknowledge her feelings and individuality. After a bitter argument, she leaves Higgins and finds herself at a crossroads — courted by the earnest but shallow Freddy Eynsford-Hill, yet still emotionally tethered to Higgins.

Higgins, meanwhile, is shocked to realize how much he has come to depend on Eliza’s presence. In the end, Eliza returns to Higgins, suggesting a complicated but enduring bond between two strong-willed individuals.

________________________________________

Analysis:

My Fair Lady is a lavish, elegant musical, but beneath its surface shines a rich, complex exploration of themes like class, identity, language, independence, and transformation.

Character Dynamics:

The heart of the film lies in the evolving relationship between Eliza and Higgins. Initially, Higgins sees Eliza as little more than a human experiment — a vessel for showcasing his own genius. Eliza, for her part, is determined but vulnerable, seeking dignity and self-worth. Over time, their rigid teacher-student relationship evolves into something more nuanced and deeply emotional. Eliza becomes a person in her own right — not just a product of Higgins’ lessons but a woman who demands respect.

Themes:

• Class and Social Mobility: The film critiques rigid class distinctions in British society, showing how superficial these boundaries are when a mere change in speech can grant access to the upper class.

• Language as Power: The ability to speak "properly" is portrayed as a tool for social advancement, but also as a potential loss of identity.

• Independence and Self-Respect: Eliza’s journey is one of self-discovery. Though Higgins "creates" a lady out of her, Eliza ultimately asserts her independence, choosing her own path and demanding recognition as an equal.

• Transformation and Authenticity: While Eliza transforms externally, the deeper question the film poses is about internal transformation. Does changing one's appearance and speech alter one's true self, or is authenticity something that survives beneath any exterior?

Style and Direction:

George Cukor’s direction is grand yet delicate. He balances opulence (the spectacular sets and costumes) with intimacy (the psychological evolution of the characters). The musical numbers are woven seamlessly into the narrative, serving not just as entertainment but as extensions of character and theme.

Music and Lyrics:

The score, composed by Frederick Loewe with lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner, is a masterpiece in its own right. Songs like "Wouldn’t It Be Loverly?", "I Could Have Danced All Night", "On the Street Where You Live", and "The Rain in Spain" are not only memorable tunes but emotional beats that trace Eliza’s transformation and Higgins’ slow, grudging emotional awakening.

Visuals and Atmosphere:

The film’s production design is rich and meticulous, from the crowded, grimy streets of Covent Garden to the polished splendor of the Embassy Ball. Cecil Beaton’s costume design is especially iconic, particularly the black-and-white Ascot scene, where stylized elegance borders on the surreal.

Cultural Context:

At its core, My Fair Lady is based on George Bernard Shaw's Pygmalion and retains much of Shaw’s sharp social critique. However, the film softens the ending compared to Shaw's play, suggesting a romantic (if still ambiguous) reconciliation between Higgins and Eliza, in keeping with Hollywood sensibilities of the time.

Main Cast:

• Audrey Hepburn as Eliza Doolittle

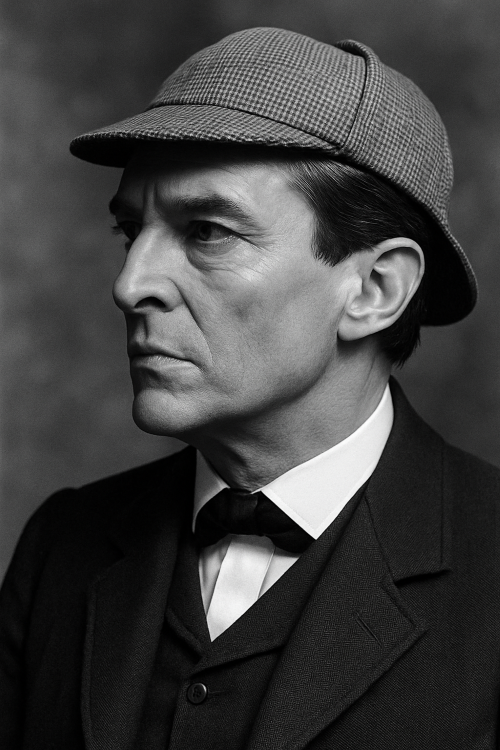

• Rex Harrison as Professor Henry Higgins

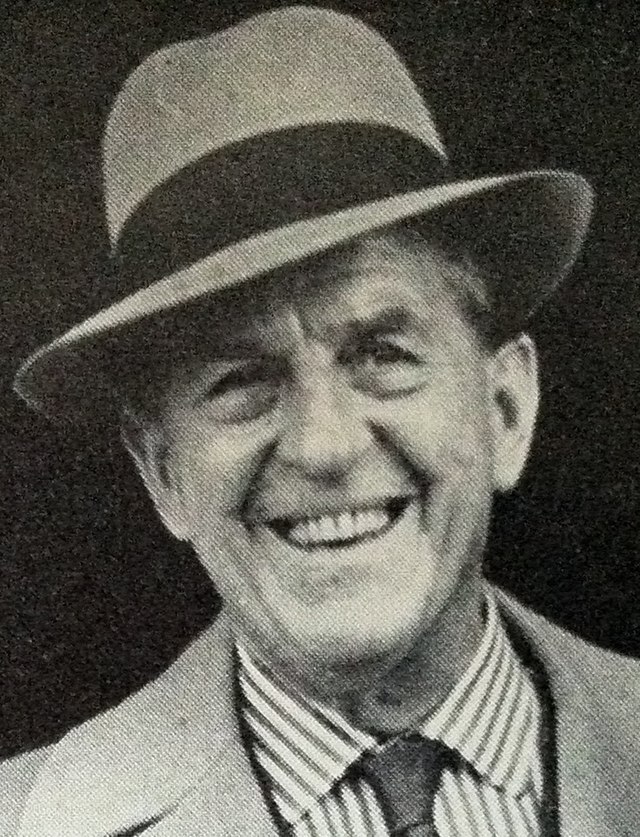

• Stanley Holloway as Alfred P. Doolittle

• Wilfrid Hyde-White as Colonel Hugh Pickering

• Gladys Cooper as Mrs. Higgins

• Jeremy Brett as Freddy Eynsford-Hill

• Theodore Bikel (voice of Zoltan Karpathy, though the onscreen role was played by a different actor — Karpathy was actually portrayed physically by Theodore Bikel’s voice mixed with actor Theodore Bikel's face in some cuts)

• Isobel Elsom as Mrs. Eynsford-Hill

• Mona Washbourne as Mrs. Pearce

• John Holland as Butler (Mrs. Higgins’ servant)

• Marjorie Bennett as Cockney woman

• Violet Farebrother as Cockney woman

• Moyna MacGill as Lady Boxington

• Olive Reeves-Smith as Queen of Transylvania

• Cecil Beaton (uncredited cameo as a Ball guest; Beaton also designed costumes and production)

________________________________________

Additional Notes:

• Audrey Hepburn’s singing voice was mostly dubbed by Marni Nixon, although Hepburn’s real voice can faintly be heard in parts of "Just You Wait" (the angry sections).

• Jeremy Brett’s singing ("On the Street Where You Live") was dubbed by Bill Shirley.

My Fair Lady Trailer

George Cukor’s Direction: A Masterclass in Elegance and Restraint

In My Fair Lady, George Cukor directs with a kind of invisible hand — a style so refined that it feels as though the story is simply unfolding naturally, without interference. Yet underneath that effortless surface lies a deep precision, a clear understanding of the delicate balances the film demands: between comedy and drama, between spectacle and intimacy, between character-driven moments and grand theatricality.

Cukor was known in Hollywood as an “actor’s director,” and in My Fair Lady, this skill is unmistakable. He approaches the towering set pieces — the lavish Embassy Ball, the dazzling Ascot races, the intricate street scenes of Covent Garden — not just as displays of grandeur but as extensions of character. Every sweeping camera movement, every meticulously composed frame, serves to illuminate the emotional journeys of Eliza and Higgins rather than overwhelm them. He treats the visual splendor as a backdrop to human transformation, never allowing the film’s ornate surface to drown out its beating heart.

Tone and Atmosphere:

Cukor captures the whimsy and charm of the musical without ever letting it become cartoonish. There's a subtle undercurrent of melancholy that runs through the film — the loneliness of Higgins, the painful self-awareness that Eliza gains, the moral compromise of Alfred P. Doolittle. Cukor allows these emotional shades to flicker quietly beneath the wit and music, enriching the story without making it heavy.

Pacing and Rhythm:

The film's pacing is graceful but deliberate. Cukor is patient, letting conversations breathe and songs unfold without rushing them. This was especially risky with a nearly three-hour running time, but it’s crucial for giving weight to Eliza's transformation. Each triumph and setback feels earned because the film takes the time to live in the moments between them.

Handling of Performances:

Cukor draws a remarkable performance from Audrey Hepburn — one of vulnerability, pride, and determination — even though much was made at the time of her singing being dubbed. He gives Hepburn the space to craft Eliza’s evolution with great subtlety. Rex Harrison, known for his talk-sing delivery, is perfectly captured in long, fluid takes that complement his style rather than cutting it to pieces.

Cukor also resists making Higgins charming in an obvious way; instead, he lets Harrison lean into Higgins' arrogance and irascibility, trusting that the audience will see the cracks in the armor when they’re ready. It's a bold, confident choice, and it keeps the character complex and compelling.

Visual Style:

Though My Fair Lady is rich in visual spectacle — from the candy-colored market scenes to the black-and-white surrealism of the Ascot race — Cukor directs with a painter’s sense of control. He knows when to step back and simply let the costumes, the sets, and the performances speak. His compositions often emphasize social divisions visually: low shots looking up at aristocrats, tight close-ups on Eliza when she feels trapped, wide, symmetrical framing during scenes where appearances are everything.

Respect for the Source Material:

Cukor honors the spirit of George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion by maintaining a sharp edge to the story’s commentary on class, manners, and identity, even within the lush trappings of a Hollywood musical. He avoids softening the characters into easy archetypes. Eliza’s triumph is not her romantic pairing with Higgins but her assertion of dignity — and Cukor preserves that hard-won self-respect through his careful, respectful handling of her arc.

In Summary:

George Cukor’s direction in My Fair Lady is a balancing act of grandeur and intimacy, theatricality and psychological depth. He orchestrates the film like a symphony — sometimes soaring, sometimes whispering — always with an unshowy mastery that allows the material and the performers to shine. His work on this film is a prime example of how great direction can be both invisible and essential, creating a world that feels complete, lived-in, and utterly transporting.

Audrey Hepburn’s Performance: A Portrait of Strength, Vulnerability, and Transformation

In My Fair Lady, Audrey Hepburn gives a performance that is often overshadowed by controversy over her singing being dubbed — but when you look past that, her portrayal of Eliza Doolittle is an extraordinary piece of physical, emotional, and psychological acting.

From the very first scene in Covent Garden, Hepburn inhabits Eliza with raw authenticity. She plays the flower girl not as a caricature of poverty but as a vibrant, scrappy survivor — dirty, yes, and shrill in voice, but bursting with pride and a fierce sense of self. Her early scenes are filled with sharp, quick movements; her body is hunched, hands are restless, eyes dart about anxiously, always on guard against humiliation. Hepburn uses her body as much as her face to show that Eliza has spent her life dodging insults, bargaining for scraps, clinging to dignity in a society that doesn’t see her.

As the transformation begins under Higgins’ stern tutelage, Hepburn layers her performance with incredible subtlety. Eliza doesn’t instantly become graceful — she struggles, stumbles, and strains, and Hepburn makes us feel the pain of every misstep. Even in scenes heavy with humor (like the "The Rain in Spain" breakthrough), there's a deep sense of effort behind Eliza’s triumphs. Hepburn shows that Eliza’s refinement isn’t magic — it’s hard-earned.

Visually, her transformation is stunning, but what’s more impressive is how gradually Hepburn alters her inner life. As Eliza’s speech improves, so too does her posture, her gestures, her very gaze. Hepburn shows Eliza growing into herself: confidence blooming awkwardly, then fully. Even as she dons spectacular gowns and enters glittering ballrooms, Hepburn lets flickers of the old, earthy Eliza show through — a quick glance, a sudden stiffening of the shoulders — reminding us that this lady has not forgotten where she came from.

Perhaps the most powerful aspect of Hepburn’s performance is her ability to convey Eliza’s deep emotional shifts without grand speeches. After the Embassy Ball, when Higgins and Pickering congratulate themselves and ignore her, Hepburn barely says a word — yet her devastation, her isolation, and her pride wounded almost beyond repair are etched across her face. It’s a masterclass in silent acting: a tight jawline, burning eyes, a fragile, trembling mouth, all speaking volumes where dialogue doesn’t.

In the final act, when Eliza confronts Higgins and finally asserts herself, Hepburn gives Eliza a new kind of strength — quieter, more composed, but utterly unbreakable. Her voice is steady, her movements deliberate. Hepburn portrays not a puppet polished by Higgins but a woman who has forged her own identity from the pieces given to her — and demands to be seen on her own terms.

Throughout the film, Hepburn maintains a delicate balance between fairy-tale magic and social realism. She is glamorous without losing grit, fragile without losing force. Even though she didn't provide her own singing voice for most of the songs, she gives full emotional meaning to them through performance — especially in numbers like "I Could Have Danced All Night," where her joy feels palpable, or in "Without You," where her newfound self-respect resounds clearly.

________________________________________

In essence:

Audrey Hepburn’s Eliza Doolittle is not just a beautiful figure of cinematic elegance — she is a fully living, breathing woman whose journey from guttersnipe to self-possessed lady is portrayed with intelligence, subtlety, and a heartaching depth that few actresses could match. Hepburn turns Eliza into a symbol of personal growth: not a creature shaped by others, but a soul that claims its own destiny.

Memorable Movie Quotes

• Professor Henry Higgins:

"The rain in Spain stays mainly in the plain."

(The famous phrase used to teach Eliza proper pronunciation.)

• Eliza Doolittle:

"I’m a good girl, I am!"

(Eliza’s defiant cry, showing her pride even when treated poorly.)

• Professor Henry Higgins:

"Why can't a woman be more like a man?"

(From the song "A Hymn to Him," revealing Higgins’ frustration and his skewed view of women.)

• Eliza Doolittle:

"The difference between a lady and a flower girl is not how she behaves, but how she is treated."

(One of the film’s central themes about class, respect, and identity.)

• Professor Henry Higgins:

"I've grown accustomed to her face."

(Higgins' reluctant admission of how deeply Eliza has affected him.)

• Alfred P. Doolittle:

"I'm willing to tell you. I'm wanting to tell you. I'm waiting to tell you!"

(Showing his humorous, shameless way of asking for money.)

• Colonel Pickering (to Higgins):

"You’ll never get away with it, you know. If you think you can turn a flower girl into a duchess in six months, you’re mad."

(Setting up the wager that drives the plot.)

• Professor Henry Higgins (mocking Eliza’s Cockney speech):

"By George, she's got it! By George, she's got it!"

(Higgins’ excitement when Eliza finally perfects her accent.)

• Eliza Doolittle (furious at Higgins):

"What’s to become of me? What’s to become of me?"

(A heartbreaking moment when she realizes she has no place left — neither in the lower class nor fully accepted among the elite.)

• Professor Henry Higgins (last line of the film):

"Eliza, where the devil are my slippers?"

(A famously ambiguous and controversial ending line — blending Higgins’ affection with his stubbornness.)

Classic Scenes

Covent Garden Opening Scene

The film opens in the bustling, chaotic market of Covent Garden, where flower girl Eliza Doolittle shouts her wares in her thick Cockney accent. The setting is full of color, grime, and humanity — a vivid tableau of London’s lower classes.

Why it’s classic:

It establishes the stark class divide that will be central to the story and immediately immerses us in Eliza’s world. Hepburn’s lively, scrappy energy here is unforgettable.

________________________________________

"Wouldn’t It Be Loverly?" Song Scene

Inside a dingy little pub-like shelter, Eliza dreams aloud about a better life in the whimsical number "Wouldn’t It Be Loverly?" She wishes for simple comforts — a warm room, a big chair, and someone who cares for her.

Why it’s classic:

This scene gives emotional depth to Eliza early on, making her not just a caricature of poverty but a relatable, hopeful human being. It’s tender, bittersweet, and beautifully staged.

________________________________________

The "Rain in Spain" Breakthrough

After countless grueling lessons, Eliza suddenly, joyfully pronounces "The rain in Spain stays mainly in the plain" correctly — a breakthrough that transforms the mood entirely. Higgins, Pickering, and Eliza erupt into celebration, dancing around the study.

Why it’s classic:

It’s the first moment Eliza truly believes she might succeed, and it’s filmed with a giddy, infectious energy. Hepburn’s sheer delight, combined with the playful choreography, makes it an irresistible turning point.

________________________________________

Ascot Racecourse Scene

At the posh Ascot races, Eliza is introduced to high society. Dressed in an extravagant black-and-white gown and giant hat, she tries to behave like a lady — until she loudly cheers for her favorite horse in pure Cockney enthusiasm ("Come on, Dover! Move your bloomin' arse!").

Why it’s classic:

This scene is a hilarious collision between Eliza’s rough roots and her polished surface. The stylized, almost surreal visual design (the costumes, the slow, formal pacing) makes it one of the film’s most visually memorable sequences.

________________________________________

The Embassy Ball

Eliza’s final test: she must pass as royalty at the glittering Embassy Ball. She moves through the crowds with stunning grace, mesmerizing everyone, including the suspicious linguist Zoltan Karpathy.

Why it’s classic:

It’s a triumphal yet poignant moment. Hepburn’s poised, luminous presence shows how far Eliza has come — yet beneath the glitter, there’s a sense that she’s playing a part, not fully belonging to this new world either.

________________________________________

Eliza’s Confrontation with Higgins ("Without You")

After being ignored and taken for granted after her Embassy Ball triumph, Eliza finally stands up to Higgins, telling him she can live without him and reclaim her own life.

Why it’s classic:

This emotional showdown is the true climax of Eliza’s character arc. Hepburn’s controlled anger and wounded pride are palpable, and Higgins’ baffled arrogance is laid bare. It’s a quiet, fierce assertion of independence.

________________________________________

Final Scene: "Where the Devil Are My Slippers?"

In the final moments, Higgins listens to a recording of Eliza’s early voice and smiles wistfully — when Eliza suddenly reappears. Instead of a romantic declaration, Higgins simply says, "Eliza, where the devil are my slippers?"

Why it’s classic:

The ending is famously ambiguous: affectionate, but unresolved. It resists a traditional love story closure, leaving their future relationship open to interpretation. Hepburn’s soft, knowing smile adds just the right emotional ambiguity.

Hidden Gems Scenes

Higgins’ Phonetic Study Room Introductions

When Eliza first comes to Higgins' house seeking lessons, there’s a wonderfully awkward, almost farcical scene where she’s treated like a scientific specimen. Higgins measures her voice with machines, records her speech, and critiques her like a lab project.

Why it’s a hidden gem:

It shows how coldly Higgins views people — especially the lower class — as puzzles to be solved, not as individuals. It sets up the emotional distance he’ll have to overcome later, and Hepburn plays Eliza's growing humiliation beautifully.

________________________________________

Alfred P. Doolittle’s "Little Bit of Luck" Scene

Alfred P. Doolittle leads a joyful, slightly chaotic street celebration with the song "With a Little Bit of Luck," dancing with his pals in the streets, singing about dodging responsibility.

Why it’s a hidden gem:

Beyond its comedic surface, this scene is a social commentary. Doolittle is happy precisely because he avoids the "morality" that middle and upper classes worship. Stanley Holloway's performance makes Doolittle both lovable and a bit sly.

________________________________________

Eliza Practicing Small Talk

There's a small but hilarious scene where Higgins tries to teach Eliza acceptable “small talk” for high society, and she keeps going off the rails with her own vivid, earthy stories ("How about them strawberries and the bird’s droppin’s?").

Why it’s a hidden gem:

It highlights just how unnatural and staged high-class conversation can be, compared to the colorful authenticity Eliza naturally brings. It’s a clever critique hidden inside a funny moment.

________________________________________

Freddy’s Helpless Romanticism ("On the Street Where You Live")

While Freddy Eynsford-Hill sings passionately outside Higgins’ house, professing his love after barely meeting Eliza, the scene shows him as earnest but ultimately superficial.

Why it’s a hidden gem:

It paints Freddy as a charming but shallow figure — a boy who falls in love with an ideal, not the real Eliza. It quietly strengthens the audience’s sense that Freddy may not be the right choice for her after all.

________________________________________

Higgins Mourning Eliza’s Absence

Before the famous final scene, there’s a quieter moment when Higgins, home alone, roams around his study, confused and irritated by Eliza’s absence. He’s so used to her presence that her disappearance unsettles him more than he’s willing to admit.

Why it’s a hidden gem:

This scene shows Higgins’ humanity creeping through his arrogance. It’s one of Rex Harrison’s most subtle pieces of acting — no speeches, just small movements, a restless pacing that betrays deeper feelings.

Clothing and Fashion

The clothing in My Fair Lady is one of its most iconic elements, designed by the legendary Cecil Beaton, who won an Oscar for his work on the film. The costumes are not just beautiful — they tell the story of Eliza’s transformation and reflect the social themes of the film.

Early Eliza (Covent Garden Look):

At the beginning, Eliza’s clothes are tattered, grimy, and heavily layered — shawls, ragged skirts, and worn boots. Her costume emphasizes her lower-class status and harsh life. The muted, earth-toned fabrics visually tie her to the dirty streets of London.

Transition Phase (During Lessons):

As Eliza starts her lessons, her clothing becomes simpler, cleaner, and more structured. She still wears practical, modest outfits, but they're neater — signaling her slow movement away from the street life without yet entering full high society.

Ascot Racecourse Scene:

Perhaps the most famous costume sequence: the black-and-white Ascot scene. All the characters wear monochromatic costumes — an artistic choice by Beaton to create a surreal, almost dreamlike atmosphere of rigid class formality.

Eliza’s stunning lace-trimmed white gown with the giant black-and-white hat is the defining fashion image of the movie. It’s sophisticated yet still just a bit extravagant — perfectly mirroring her struggle to fit in.

Embassy Ball Gown:

Eliza’s shimmering white ball gown, heavily beaded and crowned with a tiara, transforms her completely into the image of aristocratic grace. The gown is simple but radiantly elegant — soft, fluid, and unlike the stiff, restrictive fashion of the true aristocrats. It represents not just her external transformation but her inner refinement.

Professor Higgins and the Men:

Higgins, Pickering, and others are consistently dressed in tailored, traditional Edwardian menswear — morning coats, cravats, and waistcoats — representing the rigid, structured society that Eliza is being trained to enter.

________________________________________

In Short:

The costumes in My Fair Lady are visual storytelling tools — tracing Eliza’s journey from a flower girl to a lady, while also highlighting how class and appearance are deeply intertwined. Cecil Beaton’s designs are elegant, theatrical, and emotionally rich, helping to make the film’s world unforgettable.

Awards and Recognition

Academy Awards (Oscars) – 1965

Won (8 Awards):

• Best Picture – Jack L. Warner (producer)

• Best Director – George Cukor

• Best Actor – Rex Harrison (as Professor Henry Higgins)

• Best Cinematography, Color – Harry Stradling Sr.

• Best Art Direction – Color – Gene Allen, Cecil Beaton, George James Hopkins

• Best Costume Design – Color – Cecil Beaton

• Best Sound – George Groves (Warner Bros. Studio Sound Department)

• Best Music, Scoring of Music, Adaptation or Treatment – André Previn

Nominated (4 Additional Nominations):

• Best Supporting Actor – Stanley Holloway (as Alfred P. Doolittle)

• Best Supporting Actress – Gladys Cooper (as Mrs. Higgins)

• Best Film Editing – William H. Ziegler

• Best Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium – Alan Jay Lerner

________________________________________

Golden Globe Awards – 1965

Won (3 Awards):

• Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy

• Best Actor in a Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy – Rex Harrison

• Best Director – George Cukor

Nominated:

• Best Actress in a Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy – Audrey Hepburn

________________________________________

British Academy Film Awards (BAFTA) – 1965

Nominated:

• Best British Actor – Rex Harrison

• Best British Actress – Audrey Hepburn

• Best Film from any Source

(Note: It did not win at BAFTA despite the multiple nominations.)

________________________________________

Other Honors and Recognition:

• National Board of Review Awards:

o Included in the Top Ten Films of 1964

o Best Actor – Rex Harrison

• Directors Guild of America (DGA) Award:

o Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Motion Pictures – George Cukor (Won)

• Writers Guild of America (WGA) Award:

o Nominated for Best Written American Musical – Alan Jay Lerner

• Laurel Awards:

o Top Musical – 1st Place

o Top Male Musical Performance – Rex Harrison (1st Place)

o Top Female Musical Performance – Audrey Hepburn (2nd Place)

• Preservation:

o Selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" (in 2018).

________________________________________

My Fair Lady swept most of the major awards in 1964–1965, particularly at the Oscars, where it dominated both technical and artistic categories. Rex Harrison’s performance was universally praised, and George Cukor finally received his long-overdue Academy Award for directing after a long and distinguished career. While Audrey Hepburn didn’t win major awards for her role (and controversially wasn't nominated for an Oscar), her performance remains beloved.