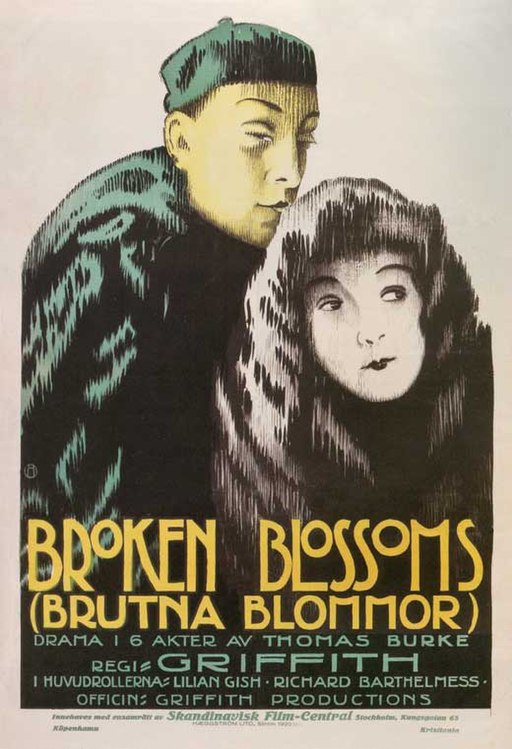

Broken Blossoms - 1919

back| Released by | United Artists |

| Director | D.W. Griffith |

| Producer | D.W. Griffith |

| Script | D.W. Griffith, adapted from Thomas Burke's short story |

| Cinematography | G.W. Bitzer |

| Music by | Silent movie |

| Running time | 90 minutes |

| Film budget | $ 90.000,- |

| Box office sales | $ 1 million |

| Main cast | Lillian Gish - Richard Barthelmess - Donald Crisp |

Broken Blossoms

Groundbreaking Drama against Prejudice

"Broken Blossoms" is notable for its sensitive portrayal of cross-cultural themes and its criticism of racism and abuse. The performances, especially by Lillian Gish, are highly praised for their emotional depth.

The film is considered a classic of the silent era, demonstrating Griffith's ability to convey complex emotions and narratives without dialogue.

Related

Broken Blossoms – 1919

"Broken Blossoms" (1919) is a silent drama that stands as a testament to D.W. Griffith's storytelling prowess, showcasing a tender yet tragic tale of love and brutality set against the backdrop of early 20th century London. The film navigates the complexities of race, violence, and redemption, all the while delivering a poignant critique of societal prejudices.

Summary

The story unfolds in the grimy and impoverished Limehouse district of London, where Cheng Huan, a young Chinese man, arrives with hopes of spreading the gentle message of Buddha to the Western world. However, the harsh realities of life in London shatter his idealism, and he becomes a shopkeeper, numbing his disillusionment with opium. His life takes a fateful turn when he encounters Lucy Burrows, a young girl brutalized by her alcoholic father, Battling Burrows, a prizefighter known for his cruelty both inside and outside the ring.

Lucy's life is one of unrelenting misery and abuse at the hands of her father. Her only moments of peace are when she escapes her grim reality, which are few and far between. Cheng Huan witnesses Lucy's suffering and becomes infatuated with her innocence and beauty. The film reaches its emotional zenith when, after a particularly savage beating by her father, Lucy stumbles into Cheng Huan's shop, barely alive.

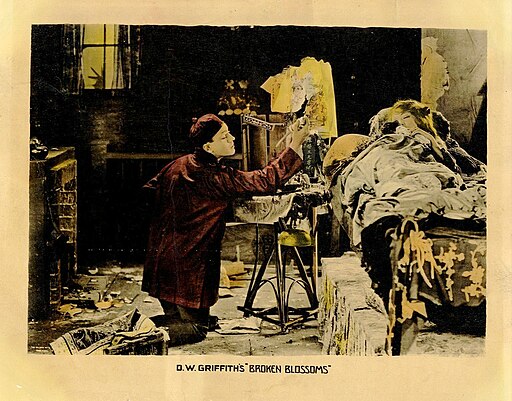

Cheng Huan cares for Lucy, nursing her back to health in his apartment above the shop. In these moments, the film portrays a bubble of serenity and kindness amidst the surrounding darkness. Their relationship blossoms into a delicate romance, characterized by Cheng Huan's gentle care and Lucy's newfound sense of safety. However, this idyll is shattered when Burrows discovers Lucy's refuge. In a fit of rage, he confronts Cheng Huan, leading to tragic consequences for all involved.

Analysis

"Broken Blossoms" is notable for its exploration of themes such as racial intolerance, abuse, and the potential for cross-cultural understanding and compassion. Griffith's direction and the performances of Lillian Gish as Lucy and Richard Barthelmess as Cheng Huan imbue the film with a depth of emotion that is striking, especially given the silent film medium's reliance on visual storytelling and expressive acting.

The film's portrayal of the relationship between Cheng Huan and Lucy challenges contemporary racial prejudices and stereotypes. It presents Cheng Huan's character with dignity and depth, a departure from the era's typical depiction of Asian characters. However, the film is not without its critics, who argue that it still conveys certain stereotypes and simplifications of Chinese culture.

The cinematography by G.W. Bitzer enhances the film's emotional and thematic depth, using light and shadow to contrast the darkness of Limehouse with the tender moments between Cheng Huan and Lucy. The use of close-ups, particularly of Gish's expressive face, deepens the viewer's emotional engagement with the characters' plights.

"Broken Blossoms" also reflects Griffith's response to the criticism of his earlier work, "The Birth of a Nation" (1915), which was condemned for its racist portrayals and glorification of the Ku Klux Klan. With "Broken Blossoms," Griffith seems to aim for a more nuanced and compassionate exploration of race and humanity, though the film's legacy is complex, embodying both progressive intentions and the limitations of its time.

In conclusion, "Broken Blossoms" remains a landmark film in cinematic history, celebrated for its emotional storytelling, innovative cinematography, and its attempt to grapple with social issues of race and violence. Despite its controversies and the dated nature of some of its content, the film's core message of compassion and understanding across cultural divides endures.

Clip from Broken Blossoms:

Cast of Broken Blossoms:

- Lillian Gish as Lucy Burrows, the tragic young girl who suffers under her father's cruelty.

- Richard Barthelmess as Cheng Huan, the gentle Chinese man who dreams of spreading the peaceful message of Buddha but finds himself disheartened by the harsh realities of London.

- Donald Crisp as Battling Burrows, Lucy's abusive father, a brutal prizefighter.

- Arthur Howard as Burrows' Manager

- Edward Peil Sr. as Evil Eye, a character who adds to the film's exploration of moral and ethical contrasts.

- George Beranger as The Spying One

- Norman Selby (also known as Kid McCoy) as A Prizefighter

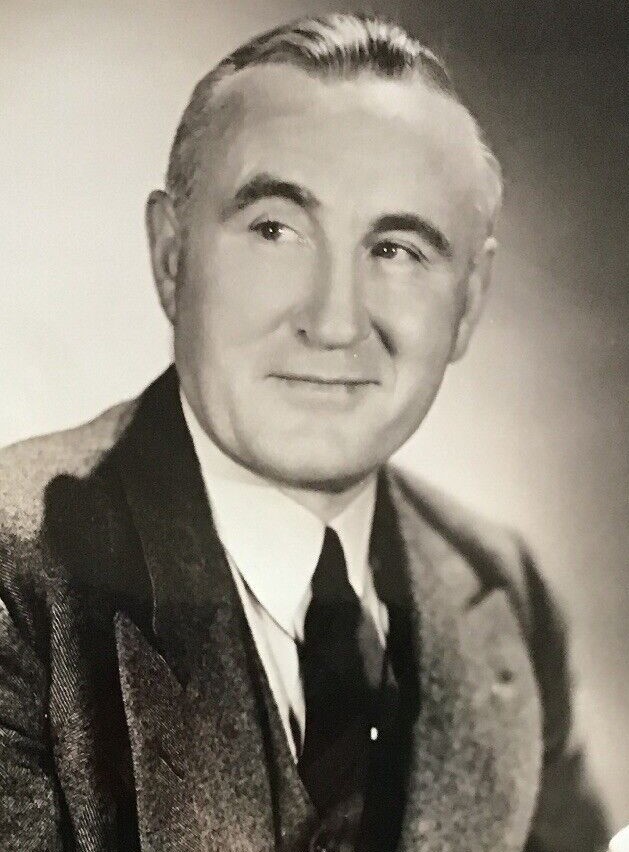

Analysis of the Direction of D.W. Griffith:

D.W. Griffith's direction in "Broken Blossoms" (1919) exemplifies his pioneering techniques and innovative storytelling that have made him a seminal figure in the history of cinema. Griffith's work on the film is notable for several key elements, including his use of close-ups, narrative pacing, and thematic depth, all of which contribute to the film's enduring legacy.

Use of Close-ups

Griffith was one of the early proponents of using close-ups to convey deep emotional states and to draw the audience into the internal world of his characters. In "Broken Blossoms," the close-ups of Lillian Gish's face are particularly powerful, capturing the nuances of Lucy's suffering, fear, and brief moments of happiness. These close-ups are not merely technical feats; they are integral to the storytelling, enabling Griffith to communicate the essence of his narrative without words.

Narrative Pacing and Structure

Griffith's mastery of narrative pacing and structure is evident in the way he builds tension and develops character arcs in "Broken Blossoms." The film unfolds at a deliberate pace, allowing the audience to fully immerse themselves in the Limehouse setting and the lives of its inhabitants. Griffith expertly juxtaposes scenes of serene tenderness between Cheng Huan and Lucy with the brutal reality of her existence under her father's roof, creating a poignant contrast that underscores the film's themes of love and cruelty.

Thematic Depth

Griffith was not afraid to tackle complex and controversial themes. In "Broken Blossoms," he explores issues such as racial prejudice, abuse, and the potential for cross-cultural understanding. Griffith's direction does not shy away from depicting the grim realities of his characters' lives, yet he also imbues the film with a sense of hope and humanity. Through his depiction of the relationship between Cheng Huan and Lucy, Griffith challenges contemporary stereotypes and invites the audience to reflect on the possibility of kindness and compassion bridging cultural divides.

Emotional Resonance

The emotional resonance of "Broken Blossoms" is a testament to Griffith's skill as a director. He was able to elicit powerful performances from his cast, particularly from Gish and Barthelmess, whose portrayals of Lucy and Cheng Huan are both nuanced and deeply moving. Griffith's use of mise-en-scène, lighting, and composition all serve to enhance the film's emotional impact, creating moments of beauty and tragedy that linger with the viewer.

Conclusion

D.W. Griffith's direction in "Broken Blossoms" is a masterclass in silent film technique, showcasing his ability to weave complex narratives, develop rich characters, and evoke profound emotional responses from the audience. His innovative use of cinematic techniques, combined with his willingness to confront difficult social themes, solidified his reputation as a trailblazer in the film industry. Despite the controversies surrounding some of his other works, "Broken Blossoms" remains a critical achievement in Griffith's oeuvre, highlighting his contributions to the art and craft of filmmaking.

Stellar Performance of Lillian Gish:

Lillian Gish's performance in "Broken Blossoms" (1919) stands as a towering achievement in the annals of cinema, showcasing her unparalleled ability to convey deep emotion and complex psychological states without the aid of spoken dialogue, a hallmark of her mastery in silent film acting.

Emotional Depth

Gish's portrayal of Lucy Burrows is a study in vulnerability and resilience. With an ethereal presence, she embodies the innocence and purity of her character, juxtaposed against the grim backdrop of London's Limehouse district and the brutality of her father's abuse. Gish uses her expressive eyes and the subtlety of her facial expressions to convey a wide range of emotions—fear, despair, hope, and tentative joy—drawing the audience deeply into Lucy's inner world. Her performance is so nuanced that viewers can almost hear her thoughts, feeling every pang of heartache and moment of fleeting happiness.

Physicality

Gish's physicality in the film is another aspect of her remarkable performance. She portrays Lucy's physical and emotional fragility with a delicate grace that is compelling to watch. Her movements are measured and purposeful, from the way she flinches and recoils in the presence of her father to the gentle way she interacts with Cheng Huan. Gish's ability to express her character's trauma through body language alone is a testament to her skill and dedication as an actress. Notably, her portrayal of Lucy's breakdown is both harrowing and deeply sympathetic, a scene that remains etched in the memory of those who witness it.

Interaction with Co-stars

The chemistry between Gish and Richard Barthelmess, who plays Cheng Huan, adds a poignant depth to their characters' relationship. Gish's interactions with Barthelmess are tender and filled with an unspoken understanding, highlighting her ability to convey complex emotions in her relationships with others on screen. Her performance is pivotal in making their doomed love story both believable and deeply moving.

Contribution to the Film's Impact

Gish's performance is central to the film's emotional impact and critical acclaim. Through her portrayal of Lucy, Gish brings to life the themes of innocence corrupted by cruelty, the longing for love and protection, and the tragedy of unfulfilled potential. Her ability to elicit empathy from the audience is a key factor in the film's enduring legacy as a masterpiece of silent cinema.

Conclusion

Lillian Gish's work in "Broken Blossoms" is a powerful demonstration of her artistry and a cornerstone of her legacy as one of silent film's greatest actresses. Her performance transcends the limitations of silent cinema, offering a masterclass in acting that continues to inspire and move audiences nearly a century later. Gish's portrayal of Lucy Burrows is not only a high point in her own career but also a seminal moment in film history, highlighting the expressive potential of cinema as a medium for profound emotional storytelling.

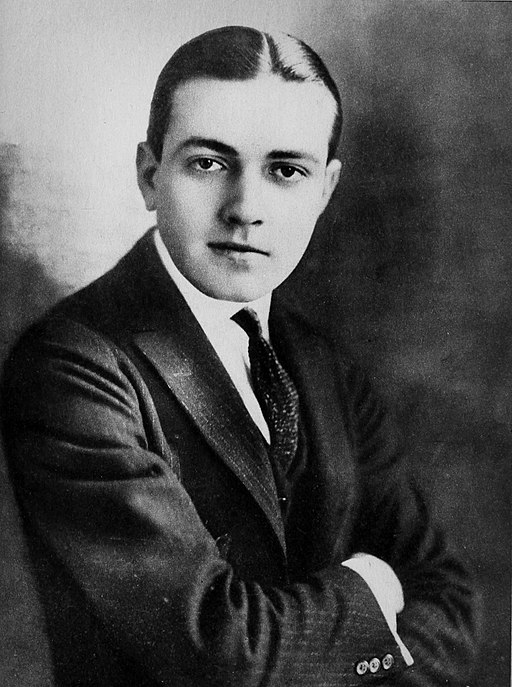

The Performance of Richard Barthelmess:

Richard Barthelmess's performance in "Broken Blossoms" (1919) as Cheng Huan, the gentle and disillusioned Chinese immigrant in London, stands out for its depth, sensitivity, and the subtle complexity he brings to the role. At a time when the film industry often resorted to broad stereotypes, particularly in portraying characters of Asian descent, Barthelmess's portrayal was notable for its dignity and humanity. Here's an analysis of his performance in the film:

Emotional Depth

Barthelmess's portrayal of Cheng Huan is marked by a profound emotional depth. He conveys a wide range of emotions, from the initial hope and idealism upon his arrival in London to his subsequent disillusionment and despair as he confronts the city's squalor and racism. Barthelmess's expressive eyes and nuanced facial expressions communicate his character's internal journey without the need for words, embodying the silent film era's emphasis on visual storytelling.

Physicality and Expression

Barthelmess's physicality in the role adds another layer to his performance. His gentle demeanor and the careful, almost reverential way he interacts with Lillian Gish's character, Lucy, convey a tenderness and compassion that transcend cultural and linguistic barriers. His body language and movements are measured and deliberate, contributing to the portrayal of Cheng Huan as a figure of peace and kindness in a brutal and chaotic world.

Subtlety and Restraint

One of the hallmarks of Barthelmess's performance is his use of subtlety and restraint. In a film that deals with themes of racism, abuse, and tragedy, his understated approach allows the audience to empathize with Cheng Huan's plight and root for his and Lucy's happiness, even as the narrative moves toward its inevitable tragic conclusion. This restraint is particularly evident in scenes where Cheng Huan cares for Lucy after rescuing her; his actions speak volumes about his character's decency and depth of feeling.

Cultural Sensitivity

While contemporary audiences may view the casting of Barthelmess, a white actor, in the role of a Chinese character through a critical lens due to the practice of "yellowface," it's important to contextualize his performance within the era's norms. Despite this, Barthelmess's respectful portrayal was praised for its sensitivity and humanity at the time, contributing to the film's critique of racial prejudice and highlighting the potential for empathy and understanding across cultural divides.

Memorable Quotes from the Title Cards:

On Cheng Huan's Mission: "The Yellow Man's heart was heavy as he saw that evil was more powerful than good."

- This card introduces Cheng Huan's disillusionment with the world he finds in London compared to the peaceful teachings he intended to spread.

Describing Lucy's Plight: "Tossed by fate into a Limehouse attic."

- A succinct description of Lucy's harsh living conditions and the lack of control she has over her life.

Lucy's Father, Battling Burrows: "Battling Burrows, one of the most brutal of the East End Prizefighters."

- This card sets the stage for understanding the violent and abusive nature of Lucy's father, highlighting the danger she faces at home.

The Encounter: "And the beauty which all Limehouse missed smote him [Cheng Huan] full."

- This quote captures the moment Cheng Huan first sees Lucy, emphasizing the immediate and profound impact her innocent beauty has on him amidst the grim surroundings.

On Compassion and Care: "He [Cheng Huan] gathered her [Lucy] up in his arms and carried her to the only home she had ever known."

- Reflecting the tenderness and care Cheng Huan offers Lucy, this card is pivotal in showcasing the film's theme of cross-cultural empathy and kindness.

Lucy's Despair: "It's the livin' that's hard."

- A simple yet powerful line that encapsulates Lucy's suffering and the bleak outlook she has on her life, filled with abuse and misery.

The Tragedy of Love: "We may believe that there is a beautiful land where the weary rest."

- Near the film's conclusion, this card philosophically reflects on the hope for peace and happiness beyond the suffering of the world, hinting at the tragic end awaiting the characters.

Recognition for “Broken Blossoms”:

- Library of Congress: "Broken Blossoms" was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress in 1996, recognizing it as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."

- Critical Acclaim: The film has been praised by critics and scholars for its direction, performances (especially by Lillian Gish and Richard Barthelmess), and its groundbreaking use of cinematic techniques.

- Film Rankings and Lists: It often appears on lists of the greatest films of the silent era and has been included in film studies and retrospectives around the world.