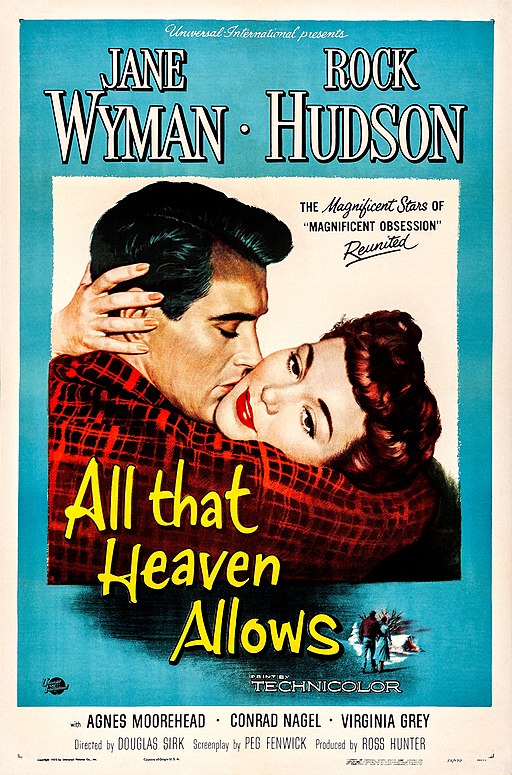

All That Heaven Allows - 1955

back| Released by | Universal Pictures |

| Director | Douglas Sirk |

| Producer | Ross Hunter |

| Script | Peg Fenwick, based upon a story by Edna L. Lee and Harry Lee |

| Cinematography | Russell Metty |

| Music by | Frank Skinner |

| Running time | 89 minutes |

| Film budget | Not released |

| Box office sales | $ 3,2 million |

| Main cast | Jane Wyman - Rock Hudson - Agnes Moorehead - Conrad Nagel |

All That Heaven Allows

A poignant critique of societal norms through a forbidden love story

"All That Heaven Allows" (1955) is a classic melodrama directed by Douglas Sirk, renowned for its rich color cinematography and incisive social commentary.

The film tells the story of Cary Scott (Jane Wyman), a wealthy widow, who falls in love with her younger, free-spirited gardener, Ron Kirby (Rock Hudson).

Set in a conservative small town, their romance faces societal scorn and familial disapproval, highlighting the era's rigid class and gender norms.

Related

All That Heaven Allows - 1955

Summary

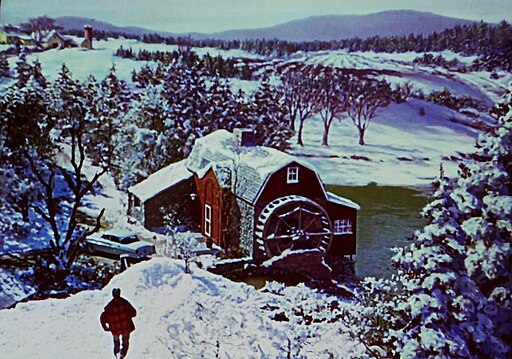

Setting: The film is set in a picturesque but conservative small town in New England during the 1950s.

Plot:

- Introduction: The story revolves around Cary Scott (Jane Wyman), a wealthy widow living a comfortable but mundane life. She has two grown children, Kay (Gloria Talbott) and Ned (William Reynolds), who are absorbed in their own lives. Cary's social life is constrained by the town's conservative values.

- Cary and Ron: Cary meets Ron Kirby (Rock Hudson), her younger and socially different gardener. Ron is a free-spirited and nature-loving man who challenges Cary's conventional life. Despite their differences in age and social status, they fall in love.

- Societal Pressure: Their relationship faces criticism and disapproval from Cary's friends, children, and the broader conservative community. Cary is subjected to gossip and judgment, highlighting the rigid social norms of the time.

- Conflict and Resolution: Cary is torn between her love for Ron and her desire to maintain her social standing and relationship with her children. After a series of events, including a serious accident involving Ron, Cary realizes the importance of true happiness over societal expectations. The film ends with Cary choosing to be with Ron, symbolizing her break from societal constraints.

Analysis

Themes:

- Social Conformity vs. Individual Happiness: The film critiques the societal norms of the 1950s, especially concerning class, gender roles, and age. Cary's struggle represents the tension between personal happiness and societal expectations.

- Love and Age Difference: The relationship between Cary and Ron challenges the taboo of an older woman being involved with a younger man, a bold topic for its time.

- Critique of Materialism: The film subtly criticizes the materialistic and appearance-focused culture of the American middle class.

Style and Technique:

- Melodrama: Sirk's direction is quintessentially melodramatic, emphasizing emotional and dramatic situations to explore deeper issues in society.

- Use of Color and Cinematography: The film is notable for its vibrant color palette and expressive cinematography by Russell Metty. The use of color often mirrors the emotional states of the characters.

- Symbolism: There is significant use of symbolism, such as the reflections in windows and mirrors, representing Cary's inner conflict and societal imprisonment.

- Subtext: The film has a rich subtext, often read as a critique of the superficiality of the American dream and the emptiness of suburban life.

Cultural Impact:

- Influence on Cinema: "All That Heaven Allows" has influenced many filmmakers and is celebrated for its aesthetic style and social commentary. It's a precursor to the 1970s melodramas that further explored similar themes.

- Legacy: The film is seen as a critical work in Douglas Sirk's career, showcasing his ability to infuse a romantic story with deep social commentary. It's also noted for its progressive portrayal of a woman's right to sexual and emotional fulfillment, regardless of age.

Original 1955 Trailer of All That Heaven Allows:

Full Cast of the Movie:

- Jane Wyman as Cary Scott

- Rock Hudson as Ron Kirby

- Agnes Moorehead as Sara Warren

- Conrad Nagel as Harvey

- Virginia Grey as Alida Anderson

- Gloria Talbott as Kay Scott

- William Reynolds as Ned Scott

- Charles Drake as Mick Anderson

- Hayden Rorke as Dr. Dan Hennessy

- Jacqueline deWit as Mona Plash

- Leigh Snowden as Jo-Ann Grisby

- Donald Curtis as Howard Hoffer

- Alex Gerry as George Warren

- Nestor Paiva as Manuel

- Forrest Lewis as Mr. Weeks

- Tol Avery as Tom Allenby

- Merry Anders as Mary Ann

- David Janssen (uncredited) as Freddie Norton

Analysis of the Direction of Douglas Sirk:

Douglas Sirk's direction, particularly in films like "All That Heaven Allows," is a remarkable study in the use of melodrama to explore and critique societal norms.

- Emotional Depth: Sirk often used melodrama to delve into the emotional lives of his characters. His films, while on the surface might seem like simple romantic dramas, are imbued with a profound exploration of human emotions and societal constraints.

- Social Critique: He harnessed melodrama as a tool to critique the societal norms of the 1950s, particularly focusing on issues of class, gender roles, and materialism.

- Vibrant Color Palette: Sirk is known for his vivid use of Technicolor. He used color to heighten emotions and to symbolically reflect the inner lives and social status of his characters.

- Composition and Framing: His compositions often include mirrors, windows, and frames within frames, symbolizing the constraints and barriers faced by his characters. This technique also suggests a dual reality – the inner world vs. the societal façade.

- Use of Objects: Sirk often used objects in the environment to symbolize the emotional states or societal positions of characters. For example, in "All That Heaven Allows," the television set given to Cary by her children symbolizes her isolation and the societal expectation of a widow's role.

- Subtextual Layers: His films are layered with subtext, often critiquing the very societal values they appear to uphold on the surface. This complex storytelling invites viewers to look beyond the apparent narrative.

- Nuanced Characters: Sirk's characters are richly drawn, often trapped in their societal roles yet yearning for more. He had a way of eliciting performances from his actors that conveyed deep longing and complex emotional undercurrents.

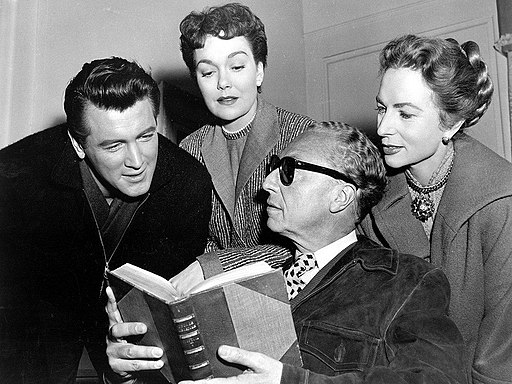

- Collaborations with Actors: Sirk often collaborated with the same actors (like Rock Hudson and Jane Wyman), who understood his style and could convey the nuanced emotions required.

- Influencing Future Filmmakers: Sirk's approach to melodrama influenced future generations of filmmakers. His ability to marry lush aesthetic beauty with social commentary has been particularly inspirational.

- Re-evaluation of His Work: Initially, Sirk's films were seen as standard Hollywood melodramas. However, over time, critics and scholars have re-evaluated his work, recognizing the depth and critique embedded in his films.

Masterful Performance of Jane Wyman:

Jane Wyman's performance in "All That Heaven Allows" is a masterclass in nuanced acting, beautifully encapsulating the internal struggles and societal pressures faced by her character, Cary Scott.

- Subtlety and Restraint: Wyman's portrayal of Cary is marked by a remarkable subtlety. She conveys deep emotions not through overt dramatics but through restrained expressions and small gestures. Her ability to communicate volumes with a simple glance or a slight change in facial expression is a testament to her skill as an actress.

- Complex Emotions: Wyman's Cary Scott is a character of many layers. She effectively portrays a range of emotions - from loneliness and longing to fear and societal pressure. Her performance reveals Cary's inner turmoil, torn between her desires and the expectations imposed on her as a widow and a mother.

- Body Language: Wyman uses her body language to great effect, often conveying Cary's emotions through her posture and movements. Her physicality shifts noticeably as Cary evolves throughout the film - from a more reserved and constrained demeanor to one that is freer and more expressive as she becomes more in tune with her desires.

- Facial Expressions: One of Wyman's most powerful tools is her expressive face. She communicates Cary's internal dialogue through subtle changes in her facial expressions, adeptly shifting from joy to sorrow, from longing to resignation.

- Chemistry with Rock Hudson: Wyman's chemistry with Rock Hudson (Ron Kirby) is central to the film's emotional impact. She portrays a convincing and evolving relationship, from initial curiosity and attraction to deeper love and connection.

- Dynamics with Supporting Characters: Wyman also excels in her interactions with the supporting cast, particularly in scenes with her children and societal peers, where she encapsulates the conflict between her personal happiness and societal obligations.

- Representation of Societal Pressure: Through her performance, Wyman brings to life the societal pressures of a 1950s widow. She encapsulates the struggle of a woman seeking personal happiness in the face of societal norms and expectations.

- Empathy and Relatability: Wyman’s portrayal makes Cary Scott a deeply empathetic and relatable character. Audiences can feel her pain, understand her dilemma, and root for her happiness.

Conclusion

Jane Wyman's performance in "All That Heaven Allows" is a powerful and poignant portrayal of a woman navigating the complexities of love, societal norms, and personal fulfillment. Her ability to convey deep emotion with subtlety and nuance, along with her dynamic interactions with other characters, makes her performance a standout not only in the film but also in the annals of classic Hollywood cinema. She brings a depth and humanity to Cary Scott that resonates with audiences, making her character's journey both compelling and emotionally impactful.

Notable Lines from the Film:

Cary Scott (Jane Wyman): "It's just that... well, I've never been alone. I've always had someone to lean on, to count on."

- This quote reflects Cary's realization of her own dependence on others and her journey towards finding self-reliance and independence.

Ron Kirby (Rock Hudson): "I want you to take a good look at exactly what's going on around here and see if it's really what you want."

- Ron encourages Cary to critically assess her life and the societal expectations imposed on her, urging her to choose a life that truly makes her happy.

Kay Scott (Gloria Talbott): "It's as though you were waiting for someone to come along, or something to happen. And then Ron came."

- Kay's observation highlights the transformative effect Ron has had on Cary's life, signifying a new beginning for her.

Sara Warren (Agnes Moorehead): "We all have to make our own mistakes."

- This line, delivered by Cary's friend Sara, emphasizes the importance of personal experience and learning from one's own choices, a central theme of the film.

Ron Kirby: "Maybe it's better to be alone, than to be in love with someone who has no courage."

- Ron's expression of disappointment in this quote underscores the central conflict of the film – the battle between true love and societal expectations.

Cary Scott: "If it's wrong to love you, then my heart just won't let me be right."

- Cary's declaration of love for Ron, despite the social norms she's breaking, highlights the depth of her feelings and her internal conflict.

Mona Plash (Jacqueline deWit): "People always talk, don't they?"

- This quote, said by a gossiping townsperson, encapsulates the small-town environment where personal affairs quickly become public discussion.

Cary Scott: "Am I supposed to let my life be ruined just so people will stop talking?"

- Cary challenges the societal pressures and gossip that threaten her happiness, showing her growing resolve and self-awareness.

Awards and Recognition:

"All That Heaven Allows" did not receive significant recognition in terms of awards and nominations upon its original release, its status and appreciation have grown considerably over time. Today, it is celebrated as a classic of mid-20th-century American cinema and a key work in Douglas Sirk's filmography.