Al Jolson (1886 – 1950)

Biography and Movie Career

Al Jolson, born Asa Yoelson on May 26, 1886, in Srednike, Kovno Governorate (modern-day Lithuania), was the youngest of four children in a Jewish family. His father, Moses Reuben Yoelson, was a rabbi who immigrated to the United States in 1891, bringing the family to Washington, D.C., in 1894. The young Asa grew up in modest circumstances and was deeply influenced by both his religious upbringing and the vibrant cultural melting pot of the capital city.

Jolson’s early life was marked by hardship. His mother, Naomi, passed away in 1894, which deeply affected him and his siblings. Seeking solace, Jolson became fascinated by entertainment, particularly the vaudeville performances that were popular at the time. He began singing in the streets and entertaining neighbors, showing an early knack for captivating audiences.

Path Toward Success

Jolson’s first foray into performance came when he joined a traveling minstrel show, performing as part of a duo with his brother Harry. By the early 1900s, Jolson had honed his skills in blackface—a controversial but common practice in the era’s minstrel shows—and developed a powerful, emotional singing style that set him apart.

In 1909, Jolson made his Broadway debut in the show La Belle Paree. His performance was a breakthrough, leading to a string of starring roles that showcased his ability to engage audiences with his larger-than-life personality. Jolson’s energetic stage presence, distinctive voice, and willingness to interact directly with his audience earned him the nickname “The World’s Greatest Entertainer.”

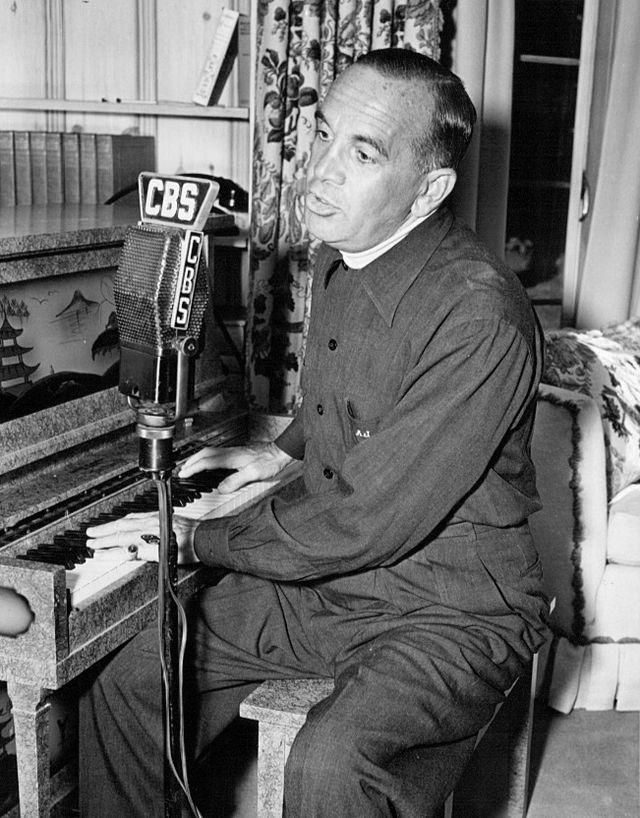

His career reached unprecedented heights in the 1920s. Jolson’s emotional renditions of songs like “My Mammy,” “Swanee,” and “April Showers” became iconic. He was a pioneer in using the microphone and other early sound technology to amplify his performances, creating an intimacy that resonated with audiences.

In 1927, Jolson starred in The Jazz Singer, the first feature-length film to include synchronized dialogue and music. This groundbreaking film marked the transition from silent films to “talkies,” cementing Jolson’s place in Hollywood history. The movie was a massive success and revolutionized the entertainment industry.

Personal Life and Marriages

Jolson’s personal life was as dynamic as his career. He married four times:

• Henrietta Keller (1907–1920): Jolson’s first marriage ended in divorce as his growing fame strained their relationship.

• Alma Osbourne (1922–1928): His second marriage also failed, with rumors of infidelity on Jolson’s part.

• Ruby Keeler (1928–1940): His third and most famous marriage was to Broadway star Ruby Keeler. Their union was highly publicized but ultimately ended in divorce.

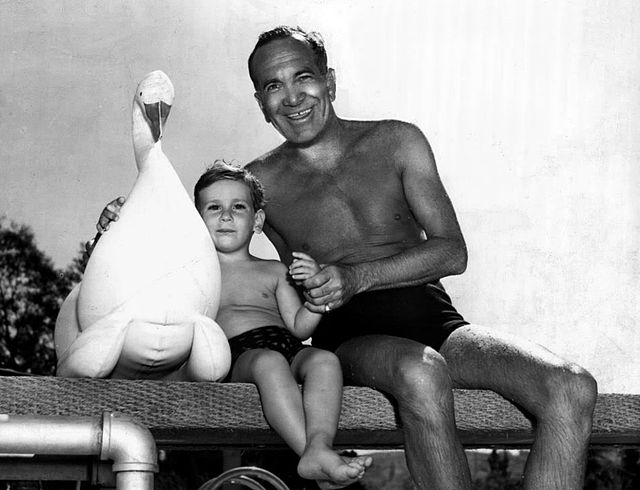

• Erle Galbraith (1945–1950): Jolson found lasting happiness with Erle, a young widow. Together, they adopted two children, Asa Jr. and Alicia, creating the family Jolson long desired.

Passions and Philanthropy

Jolson had a passion for entertaining troops. During World War II and the Korean War, he became the first entertainer to perform for soldiers overseas, earning admiration and respect. Despite being in his 60s, Jolson’s tireless dedication to boosting troop morale reflected his patriotism and love for performing. He also supported numerous charities, particularly those benefiting children and veterans.

Jolson was an early supporter of African-American artists, frequently advocating for their inclusion in mainstream entertainment. While his use of blackface has been criticized in modern times, he is remembered for his collaborations with African-American performers and for introducing audiences to jazz and blues music.

Later Years and Death

In the years following World War II, Jolson experienced a resurgence in popularity with the release of The Jolson Story (1946), a biographical film that dramatized his life and career. Larry Parks portrayed Jolson, while Jolson provided the vocals for the musical numbers. The film was a box office hit and introduced Jolson’s music to a new generation.

Despite his late-career success, Jolson’s health began to decline. Years of smoking and his relentless performance schedule took a toll on his body. On October 23, 1950, while playing cards in a San Francisco hotel room after entertaining troops in Korea, Jolson suffered a heart attack and died at the age of 64. His last words were reportedly, “Boys, I’m going.”

Legacy

Al Jolson was laid to rest at Hillside Memorial Park Cemetery in Culver City, California. His grave is marked by an elaborate tombstone that reflects his immense contributions to entertainment.

Jolson’s legacy is complex. While celebrated for his pioneering work in film, music, and stage performance, his use of blackface remains a point of contention. Nevertheless, his influence on American popular culture and the entertainment industry is undeniable, and he is remembered as one of the most transformative performers of the 20th century.

Al Jolson Sings "Swanee"

Key Characteristics of Jolson's Acting Style

• Theatricality

Jolson’s acting style was bold, expressive, and dramatic, shaped by his years in live theater. On stage, performers needed to project their emotions to the back rows, and Jolson carried this energy into his films. His gestures were often broad and exaggerated, a trait that made him captivating in musicals but occasionally appeared overstated in more subtle, narrative-driven scenes.

• Direct Audience Engagement

Jolson was a master of breaking the "fourth wall," directly addressing the audience with a smile, a wink, or a heartfelt performance. This technique, while unconventional in film, created an intimacy with viewers that mirrored his stage presence. For example, in The Jazz Singer, his famous line, "You ain't heard nothin' yet!" felt like a personal promise to the audience.

• Emotional Authenticity

Despite his theatricality, Jolson’s emotional sincerity shone through in his performances. Whether singing a sentimental ballad like "Mammy" or expressing longing and hope, he had a unique ability to convey vulnerability and passion. His performances often straddled the line between pathos and melodrama, evoking strong reactions from audiences.

• Musical Integration

Jolson's films were less about acting in a traditional sense and more about presenting him as a musical performer. His acting frequently served as a framework to showcase his singing. His physicality while performing—raising his arms, tilting his head back, and throwing himself into each note—was as much a part of his acting style as his dialogue delivery.

• Larger-than-Life Personality

Jolson’s confidence and charisma dominated the screen. He had an undeniable presence that could make even simple scenes memorable. His characters often mirrored his own public persona: bold, self-assured entertainers with a strong emotional core.

• Limited Subtlety

While Jolson’s grand gestures and emotional displays were ideal for the musicals and melodramas of his time, they sometimes lacked the nuance demanded by evolving cinematic acting styles. In films like Mammy and The Singing Kid, critics noted that his acting could feel overly reliant on the techniques of his stage career, making his characters appear somewhat one-dimensional.

• Innovative Use of Sound

Jolson’s vocal delivery was unique for his era. He used pauses, inflections, and an intimate tone to connect with audiences. His innovation in sound films, particularly his conversational singing style, set a precedent for how actors could use their voices expressively in the new medium of "talkies."

Strengths

• Jolson’s charisma was magnetic, and his ability to command attention was unparalleled.

• He excelled in conveying raw emotion through music, making his performances unforgettable.

• His energy and passion brought an infectious vitality to his roles.

Limitations

• His theatrical roots sometimes clashed with the subtler demands of film acting, especially as cinema evolved in the 1930s.

• Jolson was typecast as an entertainer, and his range as an actor was rarely tested.

• His reliance on stage conventions, such as blackface, has overshadowed his artistry in modern times.

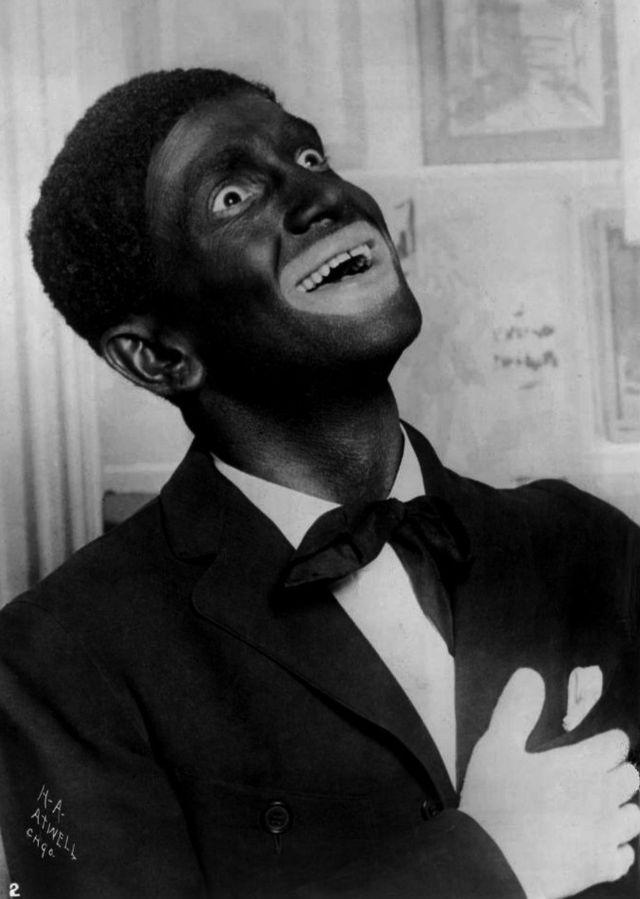

Al Jolson as Blackface

Al Jolson’s use of blackface is one of the most controversial aspects of his career, reflecting both the norms of early 20th-century entertainment and the evolving conversation around race and representation.

________________________________________

Historical Context

Blackface, a theatrical convention in the 19th and early 20th centuries, was rooted in minstrel shows that stereotyped and caricatured African-Americans. By the time Jolson began performing, blackface was a common element in vaudeville, and many entertainers, regardless of race, used it to convey certain characters or emotional expressions.

Jolson embraced blackface in his performances, both on stage and in film, most notably in The Jazz Singer (1927), where he performed songs like “My Mammy” in blackface. For him, it was a theatrical tool, a way to enhance the emotional intensity of his performances. However, today, this practice is widely recognized as perpetuating racist stereotypes and contributing to the marginalization of African-Americans.

________________________________________

Jolson’s Perspective and Contributions

Jolson saw blackface as a way to pay homage to African-American music and culture, which he admired deeply. He was an early advocate for jazz and blues, genres rooted in African-American tradition, and helped bring this music to mainstream audiences. Jolson also supported African-American artists like Cab Calloway and Eubie Blake, and he reportedly fought for their inclusion in Hollywood productions and live performances.

Despite these actions, his use of blackface—like that of his contemporaries—remains problematic. While some argue that his intent was to celebrate African-American music, others emphasize that the practice itself perpetuated demeaning stereotypes, regardless of intent.

________________________________________

Modern Reassessment

In the 21st century, Jolson’s legacy has been reevaluated. Many recognize his significant contributions to entertainment, including his role in introducing jazz and blues to broader audiences and his innovations in film. However, his use of blackface has overshadowed aspects of his career, as it is now widely understood as a harmful practice that reinforced systemic racism.

________________________________________

A Complex Legacy

Jolson’s blackface performances reflect the tensions of his time: he was a passionate performer who admired African-American culture but operated within a framework that marginalized and exploited it. His legacy is a reminder of how cultural norms evolve and the importance of critically examining historical figures and practices through a modern lens.

Film Quotes and Personal Quotes

Quotes from Films

• “You ain’t heard nothin’ yet!”

From The Jazz Singer (1927). This line became one of the most iconic quotes in film history and is often associated with the dawn of the "talkie" era. It was Jolson's way of addressing the audience and promising even more spectacular things to come.

• “Wait a minute, wait a minute. You ain't heard nothin' yet! Wait a minute, I tell ya; you ain't heard nothin'!”

Also from The Jazz Singer. This extension of the famous quote reinforced Jolson's groundbreaking interaction with his audience.

• “A jazz singer—singin’ to his God!”

From The Jazz Singer. A poignant moment that highlighted the tension between tradition and modernity, a theme central to the film.

• “I'd walk a million miles for one of your smiles.”

From the song "My Mammy," famously performed by Jolson in The Jazz Singer. Though sung rather than spoken, this phrase encapsulates the sentimentality and emotional depth of Jolson’s performances.

________________________________________

Quotes About Entertainment

• “When you’re down and out, something always turns up—and it’s usually the noses of your friends.”

Jolson’s wry sense of humor and keen understanding of human nature often came through in remarks like this.

• “I never tried to be sensational; I only wanted to be great.”

Reflecting his ambition and dedication to his craft, this quote reveals Jolson's mindset as an entertainer.

• “I don’t sing songs. I live them.”

Jolson’s description of his performance style, emphasizing the emotional connection he brought to every song.

• “No business in the world is as wonderful as show business. You work like the devil, you give your heart and soul, and then—boom!—you’re a star.”

A testament to Jolson’s passion for entertaining and his belief in the transformative power of performance.

________________________________________

Quotes on His Legacy

• “They’ve all copied me, every single one of them. But they’ll never be another Jolson.”

Jolson’s confidence in his unique talent and lasting impact on entertainment.

• “Folks, it’s not me, it’s the songs that make me a star.”

A humble acknowledgment of the timeless appeal of the music he performed, though his interpretations were often what made them memorable.

________________________________________

Patriotic and Personal Quotes

• “I’d rather be playing to 50 soldiers in a foxhole than a packed house on Broadway.”

A reflection of Jolson’s dedication to entertaining troops during wartime and his deep patriotism.

• “To hear the applause, to feel the love from an audience—that’s life. That’s what it’s all about.”

Jolson’s heartfelt expression of what performing meant to him.

• “If you can give happiness to people, then you’ve done something.”

A philosophy that drove Jolson throughout his career.

What Others said about Al Jolson

• Walter Winchell (Journalist and Columnist):

“Al Jolson was not only a great entertainer; he was the greatest. He had a magnetism, a charisma, that could fill a room with electricity.”

Winchell’s comment highlighted Jolson’s unparalleled stage presence and energy.

• George Jessel (Entertainer and Friend):

“Jolson was the Babe Ruth of entertainers. There will never be another like him. He invented what it meant to be a superstar.”

Jessel drew a parallel between Jolson’s influence in entertainment and Ruth’s in baseball.

• Bing Crosby (Singer and Actor):

“He was the greatest performer who ever lived. There was something in his voice, in his personality, that touched people deeply.”

Crosby, a musical legend himself, acknowledged Jolson’s emotional impact on audiences.

• Louis Armstrong (Jazz Icon):

“Al Jolson did a lot for jazz. He opened the door for people like me to bring our music to the big stage.”

Armstrong appreciated Jolson’s role in popularizing jazz and blues in mainstream entertainment.

• Fred Astaire (Dancer and Actor):

“Jolson was the king of them all. When he was on, nobody could touch him.”

Astaire recognized Jolson’s dominance in the entertainment world during his prime.

________________________________________

• Contemporary Critics on His Theatricality:

“Jolson’s acting could sometimes feel over the top, more suited for the vaudeville stage than the subtlety of the silver screen.”

This critique often surfaced during discussions about his transition from stage to film.

• Modern Cultural Critics on Blackface:

“While Al Jolson was a pioneer in entertainment, his use of blackface is an uncomfortable and problematic part of his legacy.”

Critics in modern times have reassessed Jolson’s career through the lens of racial sensitivity, questioning the broader implications of his performances.

• Anonymous Broadway Contemporary:

“He was a tough man to work with. He wanted everything his way, and he had no patience for anyone who didn’t match his energy.”

Jolson was known for his demanding personality and perfectionism, which sometimes alienated colleagues.

________________________________________

• Film Historian Leonard Maltin:

“Jolson’s contribution to film history cannot be overstated. The Jazz Singer changed everything, and his performance became a cultural touchstone.”

Maltin praised Jolson’s role in revolutionizing the movie industry with sound.

• Cultural Historian Michael Freedland:

“Jolson was the ultimate showman, a performer who could make you laugh, cry, and cheer all in one evening. But he was also a man of contradictions, deeply generous yet deeply insecure.”

Freedland’s nuanced view reflects Jolson’s complexity as both an artist and a person.

• Music Historian Will Friedwald:

“Jolson was the bridge between vaudeville and the modern musical. His influence on American music and performance styles is incalculable.”

Friedwald highlighted Jolson’s enduring impact on entertainment.

________________________________________

• Ruby Keeler (Actress and Former Wife):

“Al was a man who lived to perform. It was his life, his passion. But it was also what made him so hard to live with.”

Keeler offered an intimate perspective on Jolson’s dedication to his craft and its effects on his personal life.

• Eddie Cantor (Comedian and Actor):

“When Al sang, it wasn’t just a song—it was an event. He didn’t just perform; he gave you everything he had.”

Cantor celebrated Jolson’s all-in approach to performing.

________________________________________

• Audience Member (1930s):

“Seeing Jolson live was like seeing the whole world come alive. You felt like he was singing just for you.”

Many fans described Jolson’s performances as deeply personal and electrifying.

• Soldier During the Korean War:

“When Al Jolson came to entertain us, it was like a little piece of home had come all the way to the front lines.”

Jolson’s performances for the troops were remembered as moments of joy and morale-boosting during difficult times.

________________________________________

• The New York Times (Obituary, 1950):

“Al Jolson’s voice and spirit defined an era of entertainment. He was more than a performer; he was a symbol of a changing America.”

A fitting tribute to his influence on entertainment history.

• American Film Institute (Retrospective):

“Jolson’s The Jazz Singer remains a cornerstone of film history. It’s impossible to discuss the evolution of cinema without mentioning his name.”

The AFI recognized Jolson’s pivotal role in the development of sound in film.

Awards and Recognition of Al Jolson

Al Jolson's career spanned a groundbreaking era in entertainment, and while formal awards were less prevalent in his time than today, his contributions earned him a range of honors and posthumous recognition.

________________________________________

Awards During His Lifetime

• Special Academy Award Consideration

Although Al Jolson never received an Academy Award nomination, his role in The Jazz Singer (1927) was instrumental in the Academy establishing a special honorary award for Warner Bros. for producing the first "talkie." The film itself is often considered Jolson's most significant contribution to the industry.

• Star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame

Jolson was honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame for his contributions to the entertainment industry, recognizing his influence on both stage and screen.

• Recognition by Armed Forces

Jolson received commendation from the U.S. military for his tireless efforts to entertain troops during World War II and the Korean War. He was particularly beloved for being the first entertainer to perform in Korea during the war.

________________________________________

Posthumous Recognition

• The Jolson Story and Jolson Sings Again

These biographical films (The Jolson Story in 1946 and Jolson Sings Again in 1949) received critical acclaim and commercial success, helping to cement his legacy. The Jolson Story earned six Academy Award nominations, winning two, though the awards were for the production team, not Jolson himself.

• Grammy Hall of Fame

Several of Jolson’s recordings have been inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame, which honors recordings of historical significance:

Swanee (1919)

My Mammy (1921)

Rock-a-Bye Your Baby with a Dixie Melody (1918)

• International Sound & Film Award

Posthumously, The Jazz Singer is often cited in retrospectives and has been included in various honors celebrating the development of sound in film. Its cultural impact remains immense.

• Library of Congress National Film Registry

The Jazz Singer was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry in 1996 for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."

• ASCAP Film and Television Music Awards

Jolson’s contributions to American music earned him recognition from ASCAP (American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers), particularly for his role in popularizing Tin Pan Alley songs.

• Plaque at Hillside Memorial Park Cemetery

His gravesite in Culver City, California, is marked by a monument that highlights his contributions to entertainment and his legacy as "The World’s Greatest Entertainer."

• Posthumous Congressional Recognition

Jolson’s contribution to entertaining troops during wartime was acknowledged by Congress after his death, with tributes to his patriotism and efforts to boost morale.

________________________________________

Informal Recognition

• "The World's Greatest Entertainer"

Jolson was widely referred to by this title during his lifetime, a testament to his influence and popularity. The nickname reflected the enormous impact he had on audiences and the entertainment industry.

• Broadway and Vaudeville Tributes

Jolson’s name remains synonymous with the golden age of Broadway and vaudeville. Several productions and documentaries have celebrated his life and career, such as Jolson: The Musical in the 1990s.

________________________________________

Legacy Recognition

• Influence on Modern Musicals

Jolson's pioneering use of sound and music in film paved the way for future movie musicals. His influence is often acknowledged in retrospectives on cinema history.

• Rankings and Polls

Jolson has frequently appeared on lists of influential entertainers, particularly those that focus on the early 20th century. His name often features prominently in discussions about groundbreaking artists who shaped modern entertainment.

• Tributes in Popular Media

Jolson’s life and work continue to be referenced in books, documentaries, and museum exhibits focusing on early Hollywood and the transition from silent films to sound.

Movies Starring Al Jolson

Silent Films (Minor Appearances):

• A Plantation Act (1926) – A short film where Jolson performs in blackface, often considered a precursor to his later work in The Jazz Singer.

________________________________________

Feature Films:

• The Jazz Singer (1927)

The first feature-length film to feature synchronized dialogue and music. Jolson's performance in this film revolutionized the industry and made him a star in Hollywood.

• The Singing Fool (1928)

A follow-up to The Jazz Singer, this film featured hit songs like "Sonny Boy." It was even more commercially successful than its predecessor.

• Say It with Songs (1929)

Another melodrama with musical numbers, showcasing Jolson's vocal talents.

• Mammy (1930)

Jolson plays a minstrel performer. This was his first film to be shot in Technicolor for parts of the movie.

• Big Boy (1930)

Based on a Broadway show Jolson starred in, this film allowed him to showcase his comedic and musical abilities.

• Wonder Bar (1934)

A musical-comedy film where Jolson starred alongside Kay Francis and Dolores del Río.

• Go Into Your Dance (1935)

A musical drama where Jolson co-starred with his then-wife, Ruby Keeler.

• The Singing Kid (1936)

A musical where Jolson plays a down-on-his-luck singer trying to make a comeback.

• Rose of Washington Square (1939)

Jolson co-starred with Alice Faye and Tyrone Power in this musical inspired by the life of Fanny Brice.

________________________________________

Biographical Films (Jolson’s Contributions):

• The Jolson Story (1946)

A biographical film about Jolson’s life and career. Larry Parks portrayed Jolson, while Jolson himself provided the vocals.

• Jolson Sings Again (1949)

A sequel to The Jolson Story, focusing on his later years and his performances for troops during World War II.

________________________________________

Documentary Appearances:

• Rhapsody in Blue (1945) – Jolson appears as himself in this biographical film about George Gershwin.

• Screen Snapshots: Hollywood Victory Show (1945) – Jolson appears briefly in this short documentary.