Sam Peckinpah (1925 – 1984)

Sam Peckinpah Biography: A Life in Film

David Samuel Peckinpah was born on February 21, 1925, in Fresno, California, into a prominent family with deep roots in the American West. His upbringing would profoundly influence his later works, as he grew up with a strong appreciation for rugged landscapes and tales of frontier justice. Peckinpah's grandfather was a judge and congressman, and the family legacy of honor and justice played a role in shaping Sam's worldview and creative sensibilities.

Early Life and Education

Peckinpah attended Fresno High School and later joined the U.S. Marine Corps during World War II, though he did not see combat. After the war, he enrolled at Fresno State College, where he initially studied history. He later transferred to the University of Southern California (USC), where he became passionate about theater and film. His fascination with the human condition, moral ambiguity, and the psychology of violence began to emerge during this time.

Early Career in Television

Peckinpah’s entry into Hollywood was unconventional. He started as a script reader and production assistant before working as a writer for TV shows like Gunsmoke and The Rifleman. These projects allowed him to hone his storytelling skills and explore themes of law, order, and rebellion. In 1958, he created the short-lived but critically acclaimed series The Westerner, which showcased his knack for blending realism with the romanticism of the Old West.

Breakthrough in Film

Peckinpah made his directorial debut with The Deadly Companions (1961), a modest Western that hinted at his potential. However, it was Ride the High Country (1962) that marked his breakthrough. A poetic Western about aging gunslingers coming to terms with their obsolescence, the film earned critical acclaim and established Peckinpah as a director with a unique vision.

"Bloody Sam" and the Evolution of Violence in Film

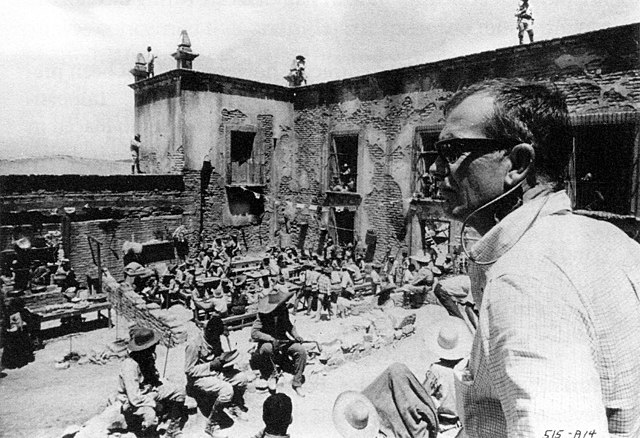

Peckinpah’s career-defining film, The Wild Bunch (1969), redefined the Western genre. Known for its graphic depictions of violence, innovative editing techniques, and morally complex characters, the film was both controversial and groundbreaking. It captured the brutal realities of a dying West and explored the costs of loyalty, betrayal, and survival. Peckinpah earned the nickname "Bloody Sam" for his unflinching portrayals of violence, which he believed reflected the human condition rather than glorified it.

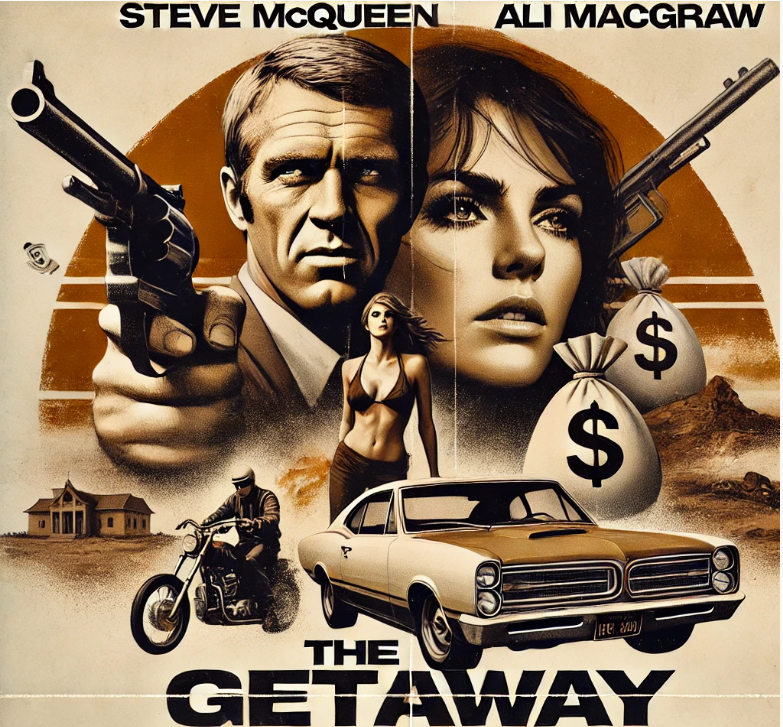

Following The Wild Bunch, Peckinpah continued to push boundaries with films like Straw Dogs (1971), a psychological thriller that examined primal instincts and the nature of aggression. The Getaway (1972) and Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973) further cemented his reputation as a filmmaker who could blend action with introspection.

Personal Life and Struggles

Peckinpah’s personal life was tumultuous. He was married twice—first to actress Marie Selland, with whom he had three children, and later to Joie Gould, a union that lasted just over a year. He also fathered a son, Kristopher, from another relationship. Peckinpah’s relationships were often strained by his volatile personality, heavy drinking, and drug use.

Known for his perfectionism and fiery temper, Peckinpah clashed frequently with studio executives, which led to several of his films being re-edited against his wishes. Despite his abrasive nature, he was deeply respected by many of the actors and crew members he worked with, as they recognized his commitment to authenticity and storytelling.

Later Career and Legacy

By the late 1970s, Peckinpah’s health began to decline due to his lifestyle. Nevertheless, he directed Cross of Iron (1977), an anti-war film set during World War II, and the commercially successful Convoy (1978), which showcased his ability to adapt to changing trends in cinema.

His final film, The Osterman Weekend (1983), was a thriller that received mixed reviews but demonstrated Peckinpah’s enduring interest in themes of paranoia and betrayal.

Sam Peckinpah died of a heart attack on December 28, 1984, at the age of 59. He was buried in Mountain View Cemetery in his hometown of Fresno, California.

Impact and Legacy

Peckinpah’s films were often polarizing, but they left an indelible mark on cinema. His innovative editing techniques, particularly his use of slow motion during action sequences, influenced generations of filmmakers, including Quentin Tarantino and Martin Scorsese. His exploration of violence, morality, and the human spirit continues to resonate with audiences and critics alike.

Peckinpah remains a towering figure in American cinema, celebrated for his raw, poetic storytelling and his ability to capture the complexities of the human experience. Though his life was marked by turmoil, his art endures as a testament to his genius.

Why Actors are Mumbling in many Sam Peckinpah Movies

Actors in Sam Peckinpah's movies often mumble or deliver their lines in a naturalistic, understated way because this approach reflects his desire for authenticity and realism.

________________________________________

Naturalistic Dialogue Delivery

• Peckinpah was committed to creating worlds that felt real and grounded. Instead of theatrical or overly enunciated performances, he encouraged actors to deliver their lines as people might in real life—sometimes quietly, with hesitation, or even under their breath.

• This style aligns with his focus on characters who are emotionally complex, often struggling with inner conflicts or reacting to tense situations.

________________________________________

Subtle Characterization

• Mumbling or understated delivery often adds depth to characters, making them seem introspective or emotionally burdened. In films like The Wild Bunch and Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia, the characters are weary, cynical, and world-weary—traits that are reinforced by their subdued manner of speaking.

________________________________________

The Influence of Method Acting

• Peckinpah worked with actors who were influenced by method acting, a style that emphasizes psychological realism and encourages actors to immerse themselves in their characters. Mumbling or breaking away from polished line delivery is a hallmark of this approach.

________________________________________

Prioritizing Atmosphere Over Clarity

• Peckinpah often prioritized mood, tone, and atmosphere over clear exposition. This approach allowed the audience to engage with the emotional subtext of a scene rather than focusing solely on the dialogue.

• His use of overlapping conversations, background noise, and fragmented dialogue added to the immersive realism but sometimes obscured individual lines.

________________________________________

Reflecting Themes of Chaos and Disillusionment

• The characters in Peckinpah’s films are frequently in chaotic, morally ambiguous worlds. Their mumbling or slurred speech mirrors their internal disarray, exhaustion, or resignation.

• For example, in Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, characters often speak quietly or indirectly, reflecting the film’s melancholic tone and the inevitability of change and loss.

________________________________________

Alcohol and Substance Abuse Depictions

• Many of Peckinpah’s characters are shown as heavy drinkers or emotionally battered individuals, which can lead to speech that feels slurred or mumbled. This mirrors their physical and emotional state, further enhancing the realism of the portrayal.

________________________________________

Criticism and Reception

While some audiences find the mumbling adds to the authenticity and rawness of his films, others see it as frustrating or as a barrier to fully understanding the dialogue. However, Peckinpah’s intent was always to emphasize mood and character over conventional clarity, making this stylistic choice an integral part of his filmmaking philosophy.

The Story of Sam Peckinpah

Sam Peckinpah’s Raw Directing Style

Sam Peckinpah’s directing style is one of the most distinctive and influential in the history of cinema. His films are characterized by their visceral realism, moral ambiguity, and innovative visual techniques. Below is an analysis of the key aspects of his style:

________________________________________

Themes of Violence and Morality

• Exploration of Violence: Peckinpah’s films are renowned for their unflinching depictions of violence. He portrayed it not as glamorous or thrilling but as chaotic, brutal, and often senseless. For Peckinpah, violence was a central part of the human experience, a tool to explore deeper themes such as survival, power, and morality.

• Moral Ambiguity: His characters rarely fit traditional molds of hero or villain. Instead, they are flawed, conflicted, and often driven by desperation or a personal code of honor. This complexity makes his stories emotionally rich and thought-provoking.

________________________________________

Editing Techniques and Visual Style

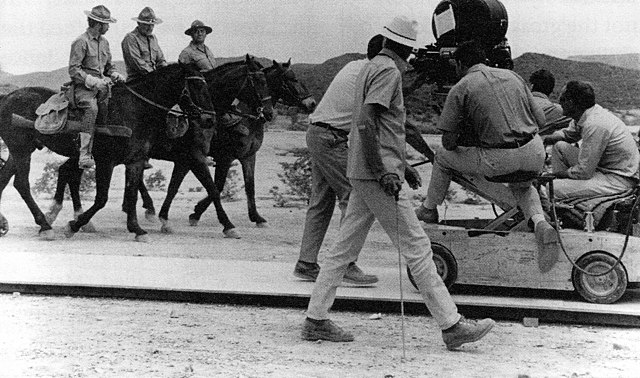

• Slow Motion and Montage: Peckinpah pioneered the use of slow motion to heighten the emotional and visual impact of violent scenes. This technique, often combined with rapid-fire editing, created a stylized yet visceral depiction of chaos. The climactic shootout in The Wild Bunch remains a landmark example.

• Multi-Angle Coverage: He frequently shot scenes from multiple angles and distances, which allowed him to create a dynamic and immersive experience during action sequences. His ability to juxtapose close-ups, medium shots, and long shots gave his films a distinctive rhythm.

• Naturalistic Cinematography: Peckinpah’s use of natural light and realistic settings enhanced the gritty, authentic feel of his films. His love of landscapes, especially in Westerns, emphasized the harsh beauty of the environments his characters inhabited.

________________________________________

Focus on Masculinity and Brotherhood

• Male Bonding: Many of Peckinpah’s films explore the camaraderie, loyalty, and betrayals among groups of men. These relationships often take center stage, as in The Wild Bunch, Ride the High Country, and Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid.

• Aging and Obsolescence: Peckinpah frequently depicted aging protagonists struggling to find their place in a changing world. His films often highlight the tension between old codes of honor and the encroachment of modernity, as seen in Ride the High Country and The Wild Bunch.

________________________________________

Subversion of Genre Conventions

• Revisionist Westerns: Peckinpah redefined the Western by dismantling its romanticized myths. His films presented a more cynical, realistic view of the frontier, emphasizing moral complexity and the harshness of the West.

• Anti-Hero Protagonists: Peckinpah’s leading characters were often deeply flawed anti-heroes, challenging the traditional archetype of the noble, virtuous protagonist. This approach made his stories feel more grounded and relatable.

________________________________________

Character-Driven Narratives

• Psychological Depth: Peckinpah’s films delve into the internal struggles of his characters. He was particularly interested in how individuals navigate extreme circumstances, often portraying their psychological unraveling.

• Strong Performances: Peckinpah was known for eliciting intense, committed performances from his actors, even amid the chaos of his often troubled productions.

________________________________________

Social and Political Undercurrents

• Critique of Modernity: Many of Peckinpah’s films lament the loss of traditional values and the rise of a more cynical, mechanized world. This is evident in The Wild Bunch, which portrays the twilight of the Old West, and Cross of Iron, which critiques the futility of war.

• Paranoia and Betrayal: Peckinpah often explored themes of distrust and betrayal, reflecting his own experiences with Hollywood studios. This is particularly evident in later films like The Osterman Weekend.

________________________________________

A Personal Vision

• Autobiographical Elements: Peckinpah’s films often mirrored his own struggles with authority, substance abuse, and personal demons. His characters’ defiance of societal norms and their self-destructive tendencies often reflected aspects of his own personality.

• Rebellious Spirit: Peckinpah was a maverick who frequently clashed with studios over creative control. His battles with censorship and editing shaped his legacy as a fiercely independent artist.

________________________________________

Influence and Legacy

Peckinpah’s directing style has left an indelible mark on cinema. Filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino, Martin Scorsese, and John Woo have cited him as a major influence. His innovative use of slow motion, dynamic editing, and morally complex storytelling set new standards for action filmmaking and narrative depth.

While Peckinpah’s career was often tumultuous and his reputation divisive, his films remain powerful, timeless explorations of human nature and the costs of violence, making him one of the most significant auteurs in film history.

Personal Quotes

On Filmmaking and Art

• "The Western is a universal frame within which it's possible to comment on today."

• "I don't want to make films that are escapist. I want to make films that explore the human condition, and sometimes that's not pretty."

• "Film is the only art form where you can create a thought process."

________________________________________

On Violence in His Films

• "The point of the violence in my films is not that it is the only thing in life, but that it's part of life."

• "Violence has always been with us. I just show it realistically. People want to avoid it, but they can't escape from it."

________________________________________

On Hollywood and the Industry

• "Hollywood has always been a cage—full of camels, parrots, and jackasses."

• "The trouble with Hollywood is they want a director who stays on time, stays on budget, and is a genius. I’ve never met one of those."

• "You work with the studios. You fight with the studios. And sometimes, you win."

________________________________________

On His Personal Philosophy

• "Life is just a series of problems. You solve one and move on to the next."

• "You can’t change what’s past, but you can still try to make it better."

• "I'm a poet, and I know it. I should have been a cowboy, but I didn’t make it."

________________________________________

On His Legacy

• "I’m not out to make headlines. I just want to make good movies."

• "My films will not fade away. They will last."

What Others said about Peckinpah

Praise for His Vision and Talent

• Martin Scorsese (Director):

“Peckinpah was a poet of violence, an artist who understood the duality of human nature. He showed us the beauty and the brutality of life in equal measure.”

• Quentin Tarantino (Director):

“Without Peckinpah, there’d be no Tarantino. The way he shot violence—it was like he painted it. He showed us that it could be ugly and beautiful at the same time.”

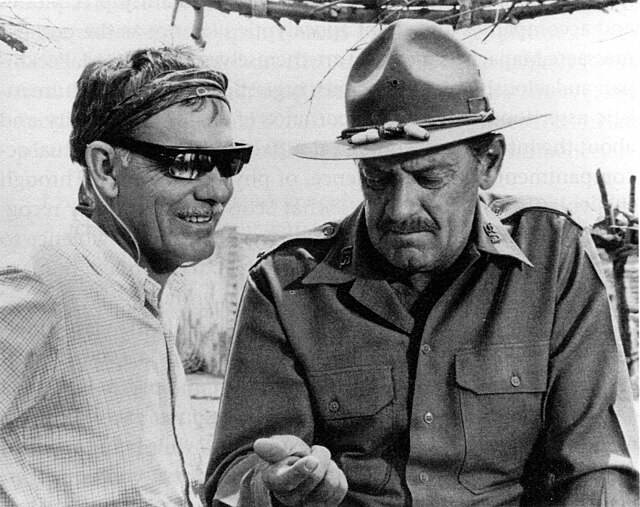

• Charlton Heston (Actor, Major Dundee):

“Sam was a genius. He had an extraordinary ability to see the poetry in the brutality, to find the humanity in even the darkest characters.”

• James Coburn (Actor, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid):

“Sam was a hard man to work with, but he was a genius. He could see things no one else could and make them real on screen.”

________________________________________

Criticism of His Behavior

• Warren Oates (Actor, Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia):

“Sam could be a tyrant, but you couldn’t help but love him. He pushed you to the edge, and sometimes over it, but the results were unforgettable.”

• Steve McQueen (Actor, Junior Bonner and The Getaway):

“Sam was brilliant, but he could be his own worst enemy. He fought battles he didn’t need to fight, and sometimes the work suffered for it.”

• Kris Kristofferson (Actor, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid):

“Sam was a wild man, no doubt about it. But he was also a genius. He saw the world differently, and he brought that vision to life.”

________________________________________

Critics on His Work

• Pauline Kael (Film Critic):

“Peckinpah’s films were never just about violence. They were about what violence does to people and how it shapes their lives.”

• Roger Ebert (Film Critic):

“Peckinpah was an artist of the highest order. He understood the complexity of human nature and wasn’t afraid to show it.”

________________________________________

Peers and Collaborators on His Personality

• Robert Culp (Actor):

“Sam was like a gunfighter—tough, dangerous, and unpredictable. But he was also tender in his own way.”

• Jerry Fielding (Composer, frequent collaborator):

“Sam had a way of making everything personal. He poured his heart into his work, and it showed, even if it drove everyone else crazy.”

________________________________________

Legacy Reflections

• Robert Altman (Director):

“Sam was one of those rare filmmakers who had a signature—a Peckinpah film was unmistakable. He created his own language.”

• Katherine Haber (Producer, Straw Dogs):

“Sam was complicated. He could be difficult, but his genius was undeniable. He saw things in people and stories that no one else saw.”

Awards and Recognition

Sam Peckinpah, despite his immense influence on cinema, was not as widely recognized by major award institutions during his career as one might expect for a filmmaker of his stature. This was likely due to the polarizing nature of his films and his frequent clashes with Hollywood studios. Nevertheless, he received some notable accolades and recognition for his work. Here is a complete overview of his awards and nominations:

________________________________________

Academy Awards (Oscars)

• Nominations: None

Despite the critical acclaim for films like The Wild Bunch and Straw Dogs, Peckinpah never received a nomination for the Oscars, reflecting the Academy's ambivalence toward his controversial style and subject matter.

________________________________________

British Academy Film Awards (BAFTAs)

• Nominations:

Straw Dogs (1971)

Nominated for Best Direction (Sam Peckinpah)

This was a major acknowledgment of Peckinpah's work on the intense and provocative psychological thriller.

________________________________________

Cannes Film Festival

• Nominations:

Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974)

Nominated for the Palme d'Or

This gritty, nihilistic film competed for the top prize at Cannes but did not win.

________________________________________

National Board of Review (NBR)

• Winner:

Ride the High Country (1962)

Won the NBR Award for Best Film

This early masterpiece was recognized for its poetic and thoughtful take on the Western genre.

________________________________________

Venice Film Festival

• Nominations:

Cross of Iron (1977)

Nominated for the Golden Lion

This anti-war film garnered attention for its harrowing portrayal of World War II.

________________________________________

Other Awards and Recognitions

• Directors Guild of America (DGA):

No nominations or awards, reflecting Peckinpah's often contentious relationships within the industry.

• American Film Institute (AFI):

The Wild Bunch (1969)

Selected as one of the AFI’s 100 Years…100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) and 100 Thrills lists, solidifying its status as one of the most influential films in American cinema.

• Critics' Awards:

Peckinpah received various accolades and recognition from critics' groups for films such as The Wild Bunch, Ride the High Country, and Straw Dogs, though these were often informal or retrospective honors.

________________________________________

Posthumous Recognition

While Peckinpah did not receive many awards during his lifetime, his legacy has been celebrated extensively after his death:

• Retrospectives and honors at major film festivals and institutions have solidified his reputation as a groundbreaking auteur.

• In 1999, The Wild Bunch was inducted into the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress for its cultural, historical, and aesthetic significance.

________________________________________

Peckinpah’s lack of formal awards recognition during his lifetime reflects the divisive nature of his work and his status as a maverick in Hollywood. Today, he is celebrated as one of the most influential and innovative directors in film history, with his legacy far outshining the awards he received.

Movies Directed by Sam Peckinpah

1961 - The Deadly Companions

Peckinpah's directorial debut, this Western follows a former Union soldier (Brian Keith) who escorts a widow (Maureen O’Hara) and her son’s coffin through dangerous Apache territory. While not a critical success, it showed early glimpses of Peckinpah's talent for exploring human relationships under duress.

________________________________________

1962 - Ride the High Country

An aging lawman (Joel McCrea) and his old friend (Randolph Scott) take a dangerous job guarding a gold shipment. Their differing moral codes lead to betrayal and redemption. This critically acclaimed film was a poetic meditation on honor and the end of the Old West.

________________________________________

1965 - Major Dundee

Set during the American Civil War, this ambitious film stars Charlton Heston as a Union officer who leads a mixed group of Union soldiers, Confederate prisoners, and civilians on a mission against Apache raiders. Troubled production issues led to studio interference, but the film remains a cult favorite.

________________________________________

1969 - The Wild Bunch

Peckinpah’s masterpiece follows an aging gang of outlaws led by Pike Bishop (William Holden) on one last violent job as they face the changing world of 1913. Known for its graphic violence and innovative editing, it redefined the Western genre and cemented Peckinpah's reputation.

________________________________________

1970 - The Ballad of Cable Hogue

This comedic Western tells the story of Cable Hogue (Jason Robards), a prospector who discovers a spring in the desert and builds a stagecoach stop. The film explores themes of resilience and the encroachment of modernity on the Old West.

________________________________________

1971 - Straw Dogs

This psychological thriller stars Dustin Hoffman as a mild-mannered American who moves to rural England with his wife (Susan George). A series of escalating conflicts with locals leads to a shocking climax. The film examines primal instincts and the capacity for violence within ordinary people.

________________________________________

1972 - Junior Bonner

A rare, reflective film in Peckinpah’s career, this character-driven drama stars Steve McQueen as a down-on-his-luck rodeo cowboy who returns home to mend family ties. It’s a tender exploration of tradition, family, and the passing of an era.

________________________________________

1972 - The Getaway

This action-packed thriller stars Steve McQueen and Ali MacGraw as a husband-and-wife duo on the run after a bank heist. With sharp pacing and explosive action, it became one of Peckinpah's biggest commercial successes.

________________________________________

1973 - Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid

This revisionist Western stars James Coburn as Pat Garrett, the aging lawman tasked with hunting down his former friend, the outlaw Billy the Kid (Kris Kristofferson). Filled with melancholic reflections on loyalty and change, the film features a haunting score by Bob Dylan, who also appears in the cast.

________________________________________

1974 - Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia

This grim and nihilistic film follows a bar pianist (Warren Oates) who is hired to retrieve the severed head of Alfredo Garcia for a Mexican crime lord. A deeply personal work, it delves into themes of greed, desperation, and moral decay.

________________________________________

1975 - The Killer Elite

This espionage action-thriller stars James Caan and Robert Duvall as former CIA operatives caught in a web of betrayal. While less critically acclaimed than Peckinpah’s other works, it offers tense action and commentary on loyalty.

________________________________________

1977 - Cross of Iron

Set on the Eastern Front during World War II, this anti-war film stars James Coburn as a disillusioned German soldier clashing with a Nazi officer obsessed with earning a medal. Brutal and unflinching, it highlights the futility of war and moral compromises of survival.

________________________________________

1978 - Convoy

Based on the country song by C.W. McCall, this action-comedy follows a group of truckers led by "Rubber Duck" (Kris Kristofferson) as they form a convoy to protest corrupt law enforcement. While commercially successful, it was a departure from Peckinpah’s darker themes.

________________________________________

1983 - The Osterman Weekend

Peckinpah’s final film is a Cold War-era thriller about a TV journalist (Rutger Hauer) manipulated by the CIA into spying on his friends, who may be Soviet agents. While unevenly received, it reflects Peckinpah’s interest in paranoia and betrayal.

Unproduced Films of Sam Peckinpah

Sam Peckinpah had several projects that he either planned, began developing, or attempted to get off the ground but were ultimately never produced. These unproduced movies offer insight into his creative ambitions and the challenges he faced in Hollywood. Here’s a list of notable examples:

________________________________________

The Texans

• Peckinpah intended to adapt George Sessions Perry's novel, a sweeping Western saga about the post-Civil War era in Texas.

• The project was envisioned as an epic that explored themes of reconstruction, revenge, and survival, similar to the scale of The Wild Bunch. However, financing and studio backing never materialized.

________________________________________

Castaway (Adaptation of Rogue Male)

• Peckinpah worked on adapting Geoffrey Household’s novel, Rogue Male, about a man who attempts to assassinate a dictator and becomes a fugitive.

• The project stalled due to conflicts with producers, but Peckinpah’s script and vision are often considered one of the great "lost films." It was later adapted into Man Hunt (1941) and a 1976 TV movie starring Peter O’Toole.

________________________________________

The Battle of Cable Street

• A historical drama about the 1936 confrontation between British fascists and anti-fascist protesters in London. Peckinpah was interested in exploring political themes and human resilience, but the project failed to gain traction with studios.

________________________________________

The Time Machine

• Peckinpah expressed interest in directing an adaptation of H.G. Wells’s classic novel, but the project never progressed beyond initial discussions. It would have been a departure from his usual themes, blending science fiction with his trademark commentary on human nature.

________________________________________

King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table

• Peckinpah envisioned a dark, revisionist take on the Arthurian legends, focusing on betrayal, violence, and moral ambiguity—hallmarks of his style.

• His approach was deemed too unconventional and risky by studios, and the project was shelved.

________________________________________

The Tin Star (Television Series)

• Peckinpah developed a TV series proposal based on his earlier success with Westerns like The Westerner. The show would have followed a former lawman navigating the complexities of frontier justice. However, his reputation for being difficult derailed the project.

________________________________________

The Dogs of War

• An adaptation of Frederick Forsyth’s novel about mercenaries involved in a coup in Africa. Peckinpah’s vision for the project clashed with the producers, and the film was eventually directed by John Irvin in 1980.

________________________________________

Adaptation of "Blood Meridian"

• Peckinpah was reportedly interested in adapting Cormac McCarthy’s novel, though there’s limited evidence of formal progress. The book’s nihilistic tone and unrelenting violence aligned with Peckinpah’s sensibilities, making it a natural fit for his style.

________________________________________

Long Arm of the Law

• A project Peckinpah worked on in the late 1970s, described as a crime thriller about corruption and justice. The concept failed to secure studio funding, partly due to Peckinpah’s declining health and reputation.

________________________________________

East of Eden (Television Miniseries)

• In the early 1980s, Peckinpah was approached to adapt John Steinbeck’s novel into a miniseries. However, creative differences with producers and Peckinpah’s deteriorating health led to his dismissal from the project.

________________________________________

Playboy and the Lady

• Peckinpah was interested in making a romantic drama about a relationship between a wealthy man and a working-class woman, set against societal pressures. The project never moved past development stages.

________________________________________

Alfredo Garcia Sequel

• After Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia, Peckinpah reportedly considered revisiting its characters and themes in a sequel. The idea was never formally developed, as the original film's mixed reception made studios reluctant.